Berlin Wool Work

In the 19th century, several developments took place that unfolded more or less rapidly or were interdependent and that are significant for the history of cross-stitch.

As already described in the chapter on samplers, traditional samplers declined significantly in number from the beginning of the 19th century and were replaced by school samplers created in needlework classes, which contributed to cross-stitch becoming the dominant embroidery technique. Another significant contribution to this development was made by a new business idea that continues to have an impact today: at the beginning of the 19th century, embroidery pattern templates began to be produced and marketed in a new way.

In its April 1800 issue, the „Journal des Luxus und der Moden“presented " mehrere kleine Werke zum Unterrichte unsrer Damen in dieser neuen bildenden Kunst"[1] with pattern templates. The first title listed was

- "Colorirte aus 10 Blättern bestehende Muster von verschiedenen Blumen, Bouquets, Medaillons, und Borden, zum Stricken in Börsen, Westen u.v.m. gezeichnet und gestochen von Philipson. Berlin 1797. Der zweyte sehr fleißig gearbeitete Heft (1798) enthält 14, der dritte (1799) 16 saubere Kupfertafeln“[2]

as well as another work published in Leipzig

- "Neue Muster zum Stricken, Sticken und Weben, oder Versuch Mahlerey mit Strickkunst zu verbinden entworfen und colorirt von Emilie Berrin“[3], das 12 Blätter mit „recht artige[n] und geschmackvolle[n] Desseins". [4]

As a third work, Bertuch mentions "bei weitem vollständigste und neueste Werk unter Allen"[5] , created by Johann Friedrich Netto and Friedrich Leonhard Lehmann

- "Die Kunst zu stricken, in ihrem ganzen Umfange; oder vollständige und gründliche Anweisung alle sowohl gewöhnliche als künstliche Arten von Strickerey nach Zeichnungen zu verfertigen […] Mit 30 illum. und schwarzen Kupfertafeln […] Leipzig 1800 […] Preis 6 Rthlr." [6]

The description "with illuminated and black copperplate engravings" means that each individual pattern was presented in both black and white and in color.

The wording of the title of the work published by Philipson and the work by Netto and Lehmann suggests that the patterns were only intended as knitting patterns. However, virtually all literature on the history of embroidery takes the view that Philipson was the first to publish a new type of embroidery pattern.[7] The title of Emilie Barrin's work supports this view, as it clearly states that the patterns could be used for several types of textile handicrafts, including embroidery. In her study on the history of crocheting, Fleischmann-Heck concludes that "die Begriffe ›Stricken‹ und ›Häkeln‹ […] zu diesem Zeitpunkt [gemeint: Ende des 18./Anfang des 19. Jhs., der Verf.] noch nicht so stark voneinander abgegrenzt [waren], wie einige Dekaden später"[8] . She substantiates this conclusion with an extensive list of publications of patterns[9] which, according to their titles, could be used for various handicrafts, including tapestry work.[10] It therefore stands to reason that the patterns published in the Journal des Luxus und der Moden between 1797 and 1800 should also be regarded as embroidery patterns.[11]The patterns are based on embroidery techniques that belong to the counted stitches, i.e., cross-stitch or tapestry stitch (half cross-stitch).

It is questionable to what extent the pattern books mentioned by Bertuch only contained patterns that had been designed in Germany or adopted from German tradition. To my knowledge, the origin of the actual patterns has not been thoroughly researched. The above-mentioned work by Emilie Berrin has a cover that advertises several works, all of which were obviously published before 1800. In contrast to the title mentioned by Bertuch and also at the beginning of the pattern collections, "Emilie Barrin und Jacques Savon neueste englische und Französische Muster zu aller Art der Stickerey für Damen, wie auch für Fabrikanten"[12] it says here. It can therefore be assumed that the patterns themselves were not a German development, but only the way in which the patterns were presented.

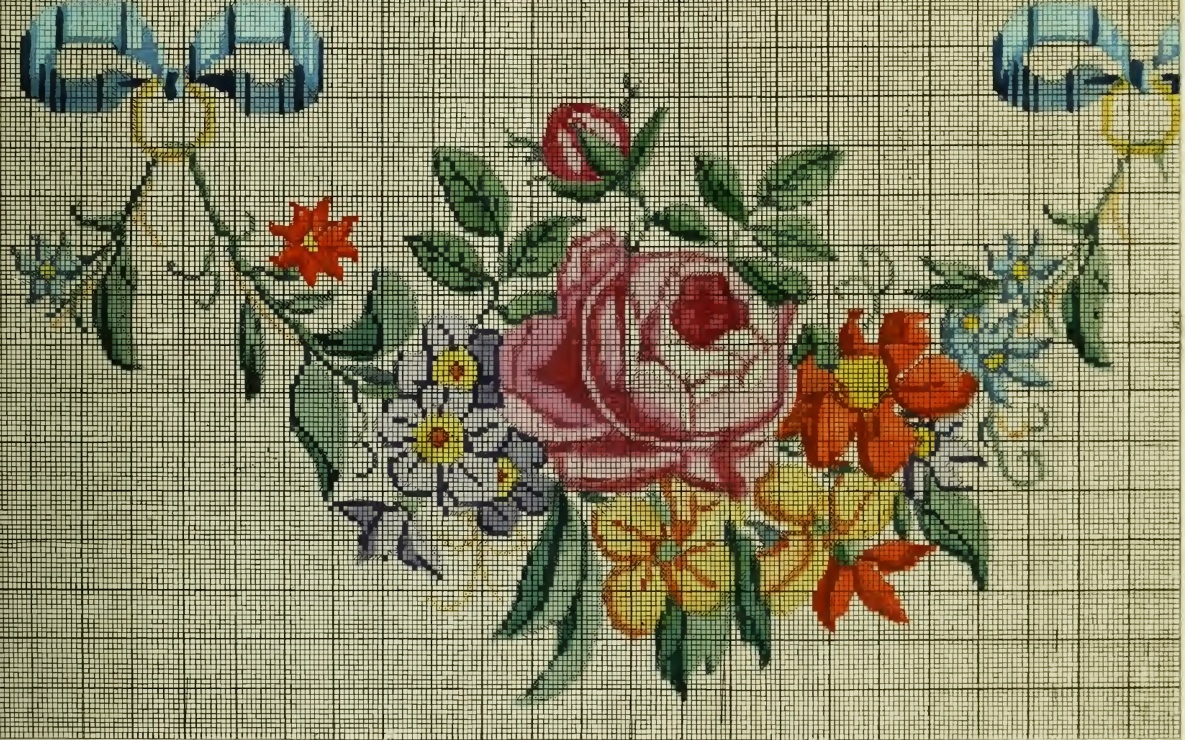

The digitization of the works by Berrin and Netto/Lehmann shows that the patterns are comparable in appearance to today's embroidery patterns. The patterns are printed on pattern paper, with each square corresponding to a cross stitch or a knitting stitch or a crochet stitch. For better readability, the grids in Berrin's work are divided into blocks of 10 crosses with slightly thicker guide lines. Berrin's patterns and the illuminated patterns by Netto and Lehmann are colored, i.e., each grid box is marked with a color that corresponds to a color of embroidery thread. These color codes, like the symbol codes in the black-and-white printed templates, allow the corresponding embroidery threads to be selected quickly and easily. Since color printing did not exist around 1800, the colored patterns had to be colored by hand. It is said that "in Berlin […] im Jahr 1840 ungefähr 1200 Heimarbeiterinnen mit dem Kolorieren der Muster beschäftigt [waren]" [13] . It was not until the invention of chromolithography in 1837[14]that hand coloring was replaced by color printing.

The digitization of the works by Berrin and Netto/Lehmann shows that the patterns are comparable in appearance to today's embroidery patterns. The patterns are printed on pattern paper, with each square corresponding to a cross stitch or a knitting stitch or a crochet stitch. For better readability, the grids in Berrin's work are divided into blocks of 10 crosses with slightly thicker guide lines. Berrin's patterns and the illuminated patterns by Netto and Lehmann are colored, i.e., each grid box is marked with a color that corresponds to a color of embroidery thread. These color codes, like the symbol codes in the black-and-white printed templates, allow the corresponding embroidery threads to be selected quickly and easily. Since color printing did not exist around 1800, the colored patterns had to be colored by hand. It is said that "in Berlin […] im Jahr 1840 ungefähr 1200 Heimarbeiterinnen mit dem Kolorieren der Muster beschäftigt [waren]" [13] . It was not until the invention of chromolithography in 1837[14]that hand coloring was replaced by color printing.

Fig. 1: Pattern from: New patterns for knitting, embroidery, and weaving, or an attempt to combine painting with knitting, designed and colored by Emilie Berrin.- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/fa/

Neue_Muster_zum_Sticken_und_Weben%2C_oder%2C_

Versuch_Mahlerei_mit_Strickkunst_.._%28IA_neuemusterzumsti

00berr%29.pdf

Neue_Muster_zum_Sticken_und_Weben%2C_oder%2C_

Versuch_Mahlerei_mit_Strickkunst_.._%28IA_neuemusterzumsti

00berr%29.pdf

This new business model was obviously very successful, as can be seen from the numerous publications mentioned by Fleischmann-Heck,[15] . What is surprising about her list is that she mentions several publications from the Philipson publishing house, because Philipson is generally regarded as having been largely unsuccessful in the literature, as his designs "being badly executed and devoid of taste, did not meet with the encouragement he expected"[16]. Instead, the actual initiator of successful embroidery patterns is said to be "Madame Wittich, a lady of great taste and an accomplished needlewoman"[17] , who persuaded her husband Ludwig Wittich to bring embroidery patterns onto the market that were "executed in such a superior manner that many of the first patterns issued from his establishment are now in as much demand as those more recently published: in fact, we very much doubt whether any, since published by other houses, have ever equalled, either in design or colouring, the earlier productions of Mr. Wittich"[18] . Other well-known companies were the publishing house Hertz und Wegener, which specialised in embroidery patterns and had also been publishing in Berlin since the first quarter of the 19th century[19] , and the publishing house Heinrich Kuehn, which was active from the middle to the second half of the 19th century.[20] The number of publishers grew rapidly, and " insgesamt sind 31 Verleger in Berlin im 19. Jahrhundert nachgewiesen“[21]. Nothing precise is known about the individual print runs, but "in 1840 it was estimated there were 14,000 patterns in circulation"[22] .

The first embroidery patterns were published in small books, which we would now refer to as leaflets, as can be seen from the titles. The 30 patterns by Netto and Lehmann were priced at 6 Reichsthaler, while Emilie Berrin's pattern collection cost 3 Reichsthaler for 12 patterns.[23] „Bald jedoch erschienen […] Musterbögen ähnlich den Bilderbögen und wurden in Auflagen von 100 Stück und mehr als Stickmustervorlagen verkauft"[24] , which were cheaper than the leaflets and therefore „auch für breitere Käuferschichten erschwinglich wurden"[25] . Over the course of the century, patterns also became available as supplements to women's magazines.[26]

The first embroidery patterns were published in small books, which we would now refer to as leaflets, as can be seen from the titles. The 30 patterns by Netto and Lehmann were priced at 6 Reichsthaler, while Emilie Berrin's pattern collection cost 3 Reichsthaler for 12 patterns.[23] „Bald jedoch erschienen […] Musterbögen ähnlich den Bilderbögen und wurden in Auflagen von 100 Stück und mehr als Stickmustervorlagen verkauft"[24] , which were cheaper than the leaflets and therefore „auch für breitere Käuferschichten erschwinglich wurden"[25] . Over the course of the century, patterns also became available as supplements to women's magazines.[26]

As mentioned above, the patterns were templates for cross-stitch embroidery over two threads or tapestry stitch over one thread on canvas and Aida[27] , stramin[28] , or linen[29] . The overwhelming majority of embroidery materials were wool, sometimes accented with silk or metal threads.[30] The embroidery wool originally came from Saxony, where sheep crossed with Spanish merino sheep had been bred since 1765. Their wool was particularly soft and could be easily divided into individual embroidery threads. "Berlin wool [...] came in three weights. The coarsest was called double; the intermediate grade, single; and the finest, split."[31]

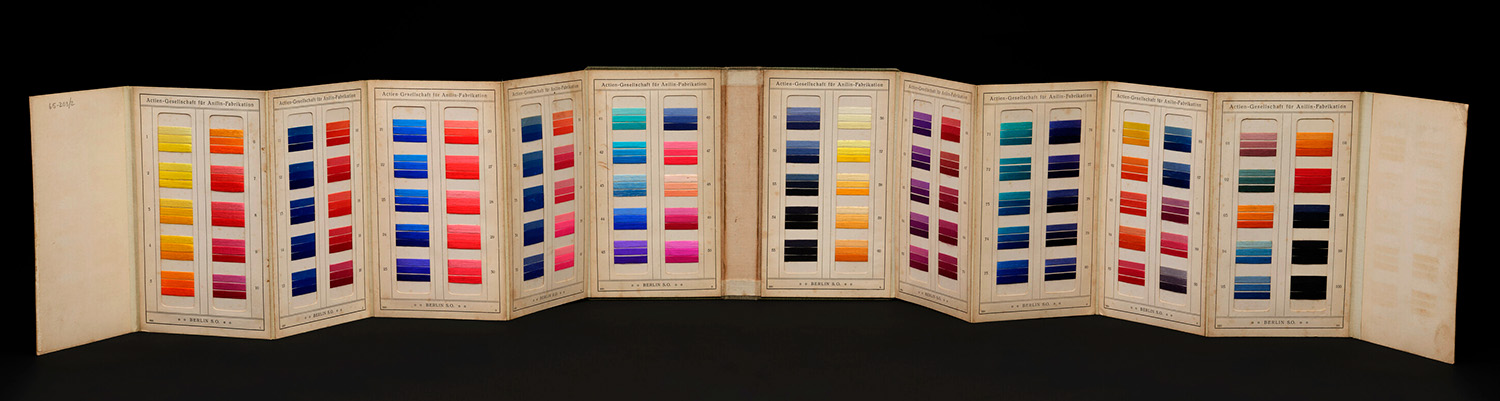

Fig. 2: Color chart of synthetic wool colors, Berliner Anilin Gesellschaft, 1900. - https://www.ashmolean.org/article/the-colour-revolution-in-victorian-fashion

"This wool may be split and worked on the finest canvas, and also doubled and trebled on the coarsest: its beauty, however, can be best appreciated when worked in a single thread on a canvas suited to its size"[32] , Miss Lambert admires. The wool was spun in Gotha, while the dyeing, manufacturing, and distribution took place in Berlin.[33] This gave the wool the name "Berlin wool" or "Zephyr," a designation that originated with Berlin wool merchants. It took to dyeing particularly well, so that it was available in many colors[34] , until the development of aniline dyes in the mid-19th century further expanded the color palette and produced particularly bright colors[35] that did not fade and, thanks to the wide range of colors available, enabled embroidery with three-dimensional effects.

The fact that the patterns, as well as the embroidery wool and materials, were mainly distributed from Berlin led to the term "Berlin wool work" or "Berlin work" for wool embroidery based on Berlin patterns.[36] This wool embroidery became world-famous under this name after the embroidery patterns were made known in London in 1831 by a shopkeeper named Wilks[37] and exports to England began, further intensified by the 1851 World's Fair in London and the emergence of women's magazines.[38] The latter also promoted the spread of "Berlin patterns" in America after 1840.[39] . Berlin wool work became a fashion trend comparable to the advent of the miniskirt in the 1960s and was also referred to as the "Berlin Wool Work Craze"[40] . Several booklets with embroidery patterns published by Heinrich Kuehn feature on their covers illustrations of statesmen or national symbols of countries where international exhibitions were held, at which Kuehn probably also presented his products. They name the respective city and year of the exhibition: 1844 the General German Trade Exhibition in Berlin, 1851 the World Exhibition in London, 1862 the World Exhibition in London, 1873 the World Exhibition in Vienna, 1879 the World Exhibitions in Philadelphia and Sydney, 1879 the Trade Exhibition in Berlin.[41] This list and the fact that it was worthwhile for Kuehn to participate in these exhibitions, which were very difficult to reach at the time, proves the popularity and demand for "Berlin wool work."

The fact that the patterns, as well as the embroidery wool and materials, were mainly distributed from Berlin led to the term "Berlin wool work" or "Berlin work" for wool embroidery based on Berlin patterns.[36] This wool embroidery became world-famous under this name after the embroidery patterns were made known in London in 1831 by a shopkeeper named Wilks[37] and exports to England began, further intensified by the 1851 World's Fair in London and the emergence of women's magazines.[38] The latter also promoted the spread of "Berlin patterns" in America after 1840.[39] . Berlin wool work became a fashion trend comparable to the advent of the miniskirt in the 1960s and was also referred to as the "Berlin Wool Work Craze"[40] . Several booklets with embroidery patterns published by Heinrich Kuehn feature on their covers illustrations of statesmen or national symbols of countries where international exhibitions were held, at which Kuehn probably also presented his products. They name the respective city and year of the exhibition: 1844 the General German Trade Exhibition in Berlin, 1851 the World Exhibition in London, 1862 the World Exhibition in London, 1873 the World Exhibition in Vienna, 1879 the World Exhibitions in Philadelphia and Sydney, 1879 the Trade Exhibition in Berlin.[41] This list and the fact that it was worthwhile for Kuehn to participate in these exhibitions, which were very difficult to reach at the time, proves the popularity and demand for "Berlin wool work."

Fig. 3: Heinrich Kuehn, Vereinigte Stickmuster-Verläge, embroidery pattern book no. 555, 1900.- https://www.antiquepatternlibrary.org/html/warm/N-YS001.htm

When asking about the reasons for the success of these printed embroidery patterns, it is important to consider how they differed from the embroidery patterns that were on the market before 1797. The affordability of the embroidery patterns certainly played a significant role. The model books and the first leaflets with "Berlin patterns" were expensive. However, as described above, publishers quickly moved on to publishing individual patterns, which were much cheaper and therefore affordable for a wider range of people. Other factors were no less important, however. On the page about model books, I have presented various embroidery pattern books, all of which are also printed on pattern paper. The books contain borders, tendrils, flowers, mostly stylized animals and people, etc., all printed in black and white. The motifs were "individual," i.e., they represented components whose arrangement on an embroidery had to be determined by the person doing the embroidery. Many of the motifs were also designed to be repeated, i.e. the pattern books showed one or two repeats, which were then used for borders, tendrils, or parts of a sampler. The black-and-white printing meant that the person doing the embroidery either had to embroider the pattern in one color or choose the colors for a multicolored embroidery themselves. These requirements meant that the person doing the embroidery not only had to have a minimum of mathematical skills, but also imagination and creativity in order to achieve an attractive embroidery result. As a result, every embroidery based on the pattern books was necessarily unique. As an alternative to this laborious work, it was possible to copy patterns from a sampler or to draw existing pattern designs onto the base fabric or trace them. For the tracing technique, the paper patterns were placed on the fabric and the contours were perforated at small intervals. By applying a powder to the perforated paper, the contours were then transferred to the fabric, where they could be embroidered.[42] In contrast, the "Berlin patterns" were designed from the outset for pictorial motifs, i.e., the composition was already predetermined, which greatly simplified the embroidery. In addition, the fact that the color selection was also predetermined simplified the implementation of the patterns into a harmonious embroidery. The professionally created designs made it possible to deviate from the traditional patterns and bring new motifs to the market. They allowed the patterns to be used for a wide variety of purposes, whether as wall hangings, textile decorations, furniture covers, and much more. This was also helped by the fact that the "Berlin patterns" mostly covered the entire embroidery base, giving the embroidery the strength it needed for its purpose. Overall, the "Berlin patterns" simplified embroidery enormously, but this came at the expense of creativity and individuality in favor of conformity in mass-produced goods.

In addition to the reasons mentioned above, the "Berlin wool work" boom was also promoted by economic and social developments and the zeitgeist. On the one hand, the period was marked by industrialization, which began earlier in England than in Germany. In both countries (as well as in other predominantly European countries and in America), it was a time of inventions and innovations that accelerated so rapidly that it is not without reason that we speak of an Industrial Revolution. New scientific inventions led to technological progress, and new machines enabled a new organization of product manufacturing and work. Trade increased, and with it communication, which reached further and spread faster than before. Many people quickly realized that industrial inventions made their lives easier. This also applied to handicrafts. In particular, the manufacture of clothing and linen was made considerably easier from the middle of the 19th century onwards by the invention of the embroidery machine in 1829[43] and the sewing machine as early as 1790[44], when both machines had been developed to such an extent that they were suitable for everyday use. Even though nothing is known about the motivation of the "inventors" of the "Berlin patterns," it can be assumed that they intended to make embroidery easier through modernization. As in many other areas, the "Berlin patterns" also attracted a string of new related industries: "Neben der Entstehung von Wollfärbereien, Kanevasfabriken und Tapisseriemanufakturen in Berlin entstand auch eine Industrie, die farbige Wollgarne in einer breiten Palette herstellte."[45]

Economic change was accompanied by social change: industrialization gave rise to a new middle class, which included craftsmen who seized the opportunity to expand their businesses through new production methods and became business owners. Simple traders were able to become small business owners through skill and a willingness to take risks. Both groups created jobs for the production and administration of their companies, with the latter contributing significantly to the growth of the middle class, as jobs in company administration required education, which in turn was a vehicle for social advancement. Here, too, due to a number of favorable factors, this development took place much earlier in England than in Germany. Stepanova describes the consequence that "as their incomes increased, middle-class homeowners could hire more household help, freeing their wives from some daily chores and giving them more time to devote to their needlework and the decoration of their homes"[46]. Owning a house and decorating it, as well as the fact that the wife did not need to work, were supposed to reflect the husband's success. Rather, "charity work and embroidery [...] were now counted among the few acceptable pastimes"[47] for the middle class as well. Combined with the Victorian ideal of domesticity, it is not surprising against this backdrop that Berlin wool work was "among the first amateur needlework techniques to become all the rage for middle-class women in Victorian England"[48].

Development in Germany was delayed in that industrialization, due to backwardness in many areas, led to the emergence of an industrial middle class much later. However, Germany did have a middle class consisting of the administrative officials required in many small states and only a few wealthy craftsmen and merchants. This middle class was characterized by its orientation toward the ideal of the "bourgeois housewife"[49] and its behavior modeled on the next higher class. Similar to England, "die Befreiung der bürgerlichen Frau von der Erwerbsarbeit"[50] was attributed to the position of men and contributed to their social prestige. "Arbeit wurde gleichgesetzt mit Erwerbstätigkeit; diese galt als rein männliche Aufgabe und daher als höchst unweiblich."[51] Handicrafts, especially embroidery, which served no useful purpose but rather beautification, were considered a befitting activity, even though middle-class women often secretly contributed to the family income through " verschämte Arbeit."[52] This attitude, which was focused on maintaining status and social advancement, changed after the end of the Wars of Liberation against Napoleon and the failure of the attempt to establish a German nation state, insofar as the bourgeois middle class in particular directed its ambitions towards creating a harmonious and aesthetically sophisticated home. The romantic and Biedermeier ideal of conviviality and friendship " verallgemeinerte […] die Beschäftigung mit Stickereien im Laufe der ersten Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts über die bürgerlichen und adligen Gesellschaftsschichten hinweg und glich sich an."[53] , to which the availability of "Berlin patterns" contributed significantly. Bergemann emphasizes that "die ständigen Bemühungen der Verleger, die Herstellungskosten zu reduzieren, die Möglichkeit wochenweise Stickmustervorlagen zu leihen, sowie das bald eingeführte Angebot standardisierter Fertigpakete mit Stickgrund, Stickgarnen und eventuell teilweise ausgeführten Stickmotiven […] die Verbreitung der Stickmode in immer einfachere bürgerliche Schichten [ermöglichte]"[54]. "Sowohl hochadlige als auch gewöhnliche adlige Damen stickten in Gesellschaft,"[55] so that "das Sticken zumindest in den adligen und gutbürgerlichen Kreisen […] einen festen Bestandteil des gesellschaftlichen Lebens [darstellte]."[56] Women from all walks of life embroidered not only for their own needs, such as marking their laundry and embellishing their clothing, but also out of social convention, as a pastime, and for pleasure.[57]

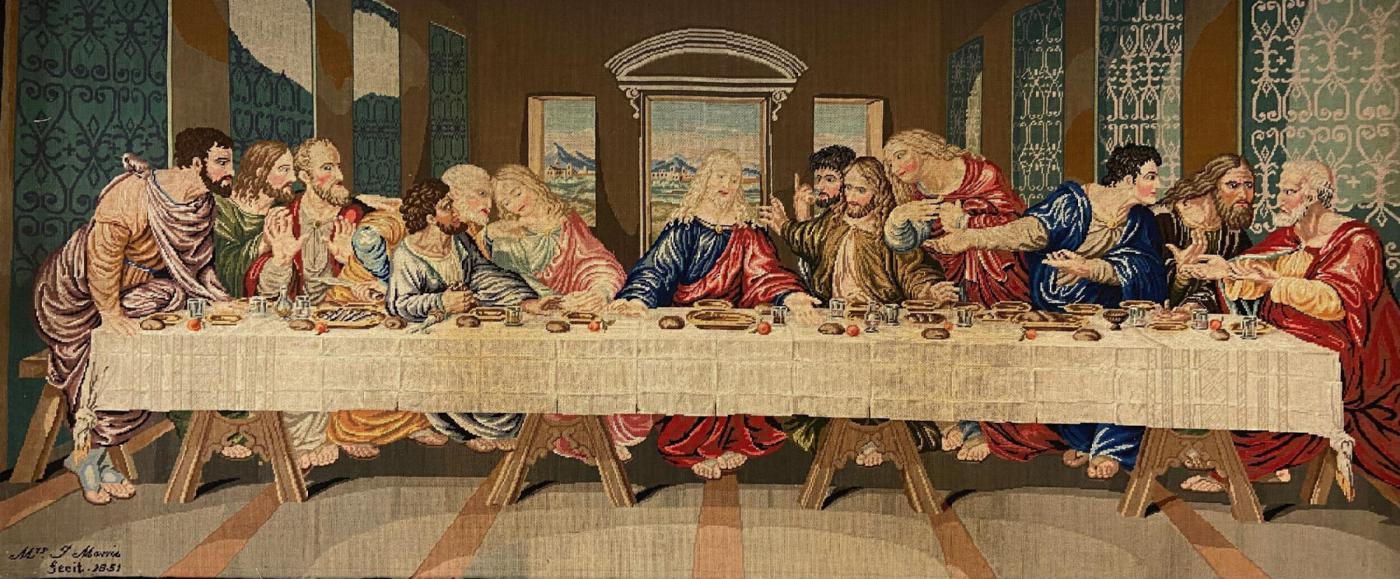

The ease with which the Berlin embroidery patterns could be reproduced and the possibilities offered by the patterns with their shading and three-dimensional effect led to a veritable flood of embroidery. Cross-stitch embroidery adorned "unterschiedliche Raumdekorationen und Möbelbespannungen"[58] and was „als Dekoration für alle möglichen Gegenstände der Hausausstattung und für Accessoires verwendet wie Taschen, Mäppchen, Etuis, Buchdeckel, Schreibmappen und Briefbeschwerer, für Bezüge von Polstermöbeln und Kaminschirmen, für Vorhänge, Teppiche, Kissen, Decken, Klingelzüge, Wandbehälter und vieler mehr, weniger allerdings für Kleidung, abgesehen von Pantoffeln, Strumpf- und Hosenbändern"[59]. A significant proportion of the embroidery was also used for gifts, as it was part of the cult of friendship in the Romantic and Biedermeier periods "eigenhändig gearbeitete Freundschafts- oder Liebesgeschenke als Ausdruck besonders inniger Beziehungen in großer Zahl herzustellen"[60]. Motifs included "Girlanden und Kränze aus Rosen, Tulpen, Nelken, Vergissmeinnicht und Eichenlaub"[61] and encompassed "animals, pets, children, religious subjects, and reproductions of famous paintings"[62] . In addition, there were " Freundschaftsenbleme[n], Tempel[n], […] Geschichts- und Landschaftsdarstellungen.“[63]

In addition to the reasons mentioned above, the "Berlin wool work" boom was also promoted by economic and social developments and the zeitgeist. On the one hand, the period was marked by industrialization, which began earlier in England than in Germany. In both countries (as well as in other predominantly European countries and in America), it was a time of inventions and innovations that accelerated so rapidly that it is not without reason that we speak of an Industrial Revolution. New scientific inventions led to technological progress, and new machines enabled a new organization of product manufacturing and work. Trade increased, and with it communication, which reached further and spread faster than before. Many people quickly realized that industrial inventions made their lives easier. This also applied to handicrafts. In particular, the manufacture of clothing and linen was made considerably easier from the middle of the 19th century onwards by the invention of the embroidery machine in 1829[43] and the sewing machine as early as 1790[44], when both machines had been developed to such an extent that they were suitable for everyday use. Even though nothing is known about the motivation of the "inventors" of the "Berlin patterns," it can be assumed that they intended to make embroidery easier through modernization. As in many other areas, the "Berlin patterns" also attracted a string of new related industries: "Neben der Entstehung von Wollfärbereien, Kanevasfabriken und Tapisseriemanufakturen in Berlin entstand auch eine Industrie, die farbige Wollgarne in einer breiten Palette herstellte."[45]

Economic change was accompanied by social change: industrialization gave rise to a new middle class, which included craftsmen who seized the opportunity to expand their businesses through new production methods and became business owners. Simple traders were able to become small business owners through skill and a willingness to take risks. Both groups created jobs for the production and administration of their companies, with the latter contributing significantly to the growth of the middle class, as jobs in company administration required education, which in turn was a vehicle for social advancement. Here, too, due to a number of favorable factors, this development took place much earlier in England than in Germany. Stepanova describes the consequence that "as their incomes increased, middle-class homeowners could hire more household help, freeing their wives from some daily chores and giving them more time to devote to their needlework and the decoration of their homes"[46]. Owning a house and decorating it, as well as the fact that the wife did not need to work, were supposed to reflect the husband's success. Rather, "charity work and embroidery [...] were now counted among the few acceptable pastimes"[47] for the middle class as well. Combined with the Victorian ideal of domesticity, it is not surprising against this backdrop that Berlin wool work was "among the first amateur needlework techniques to become all the rage for middle-class women in Victorian England"[48].

Development in Germany was delayed in that industrialization, due to backwardness in many areas, led to the emergence of an industrial middle class much later. However, Germany did have a middle class consisting of the administrative officials required in many small states and only a few wealthy craftsmen and merchants. This middle class was characterized by its orientation toward the ideal of the "bourgeois housewife"[49] and its behavior modeled on the next higher class. Similar to England, "die Befreiung der bürgerlichen Frau von der Erwerbsarbeit"[50] was attributed to the position of men and contributed to their social prestige. "Arbeit wurde gleichgesetzt mit Erwerbstätigkeit; diese galt als rein männliche Aufgabe und daher als höchst unweiblich."[51] Handicrafts, especially embroidery, which served no useful purpose but rather beautification, were considered a befitting activity, even though middle-class women often secretly contributed to the family income through " verschämte Arbeit."[52] This attitude, which was focused on maintaining status and social advancement, changed after the end of the Wars of Liberation against Napoleon and the failure of the attempt to establish a German nation state, insofar as the bourgeois middle class in particular directed its ambitions towards creating a harmonious and aesthetically sophisticated home. The romantic and Biedermeier ideal of conviviality and friendship " verallgemeinerte […] die Beschäftigung mit Stickereien im Laufe der ersten Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts über die bürgerlichen und adligen Gesellschaftsschichten hinweg und glich sich an."[53] , to which the availability of "Berlin patterns" contributed significantly. Bergemann emphasizes that "die ständigen Bemühungen der Verleger, die Herstellungskosten zu reduzieren, die Möglichkeit wochenweise Stickmustervorlagen zu leihen, sowie das bald eingeführte Angebot standardisierter Fertigpakete mit Stickgrund, Stickgarnen und eventuell teilweise ausgeführten Stickmotiven […] die Verbreitung der Stickmode in immer einfachere bürgerliche Schichten [ermöglichte]"[54]. "Sowohl hochadlige als auch gewöhnliche adlige Damen stickten in Gesellschaft,"[55] so that "das Sticken zumindest in den adligen und gutbürgerlichen Kreisen […] einen festen Bestandteil des gesellschaftlichen Lebens [darstellte]."[56] Women from all walks of life embroidered not only for their own needs, such as marking their laundry and embellishing their clothing, but also out of social convention, as a pastime, and for pleasure.[57]

The ease with which the Berlin embroidery patterns could be reproduced and the possibilities offered by the patterns with their shading and three-dimensional effect led to a veritable flood of embroidery. Cross-stitch embroidery adorned "unterschiedliche Raumdekorationen und Möbelbespannungen"[58] and was „als Dekoration für alle möglichen Gegenstände der Hausausstattung und für Accessoires verwendet wie Taschen, Mäppchen, Etuis, Buchdeckel, Schreibmappen und Briefbeschwerer, für Bezüge von Polstermöbeln und Kaminschirmen, für Vorhänge, Teppiche, Kissen, Decken, Klingelzüge, Wandbehälter und vieler mehr, weniger allerdings für Kleidung, abgesehen von Pantoffeln, Strumpf- und Hosenbändern"[59]. A significant proportion of the embroidery was also used for gifts, as it was part of the cult of friendship in the Romantic and Biedermeier periods "eigenhändig gearbeitete Freundschafts- oder Liebesgeschenke als Ausdruck besonders inniger Beziehungen in großer Zahl herzustellen"[60]. Motifs included "Girlanden und Kränze aus Rosen, Tulpen, Nelken, Vergissmeinnicht und Eichenlaub"[61] and encompassed "animals, pets, children, religious subjects, and reproductions of famous paintings"[62] . In addition, there were " Freundschaftsenbleme[n], Tempel[n], […] Geschichts- und Landschaftsdarstellungen.“[63]

Fig. 4: Picture in Berlin Wool Work, 1840-1860. In addition to the "simple" cross stitch, a raised effect is achieved here by placing wool threads on the linen and then securing them with cross stitches.- https://philamuseum.org/collection/

object/82881

object/82881

Fig. 5: Men's slippers in Berlin Wool Work, ca. 1850-1875.- https://philamuseum.org/collection/

object/129256

object/129256

Fig. 6: Embroidery for a firescreen, ca. 1850. The background is not embroidered.- https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O16657/

firescreen-panel-unknown/

firescreen-panel-unknown/

Fig. 7: Armchair with Berlin Wool Work upholstery, ca. 1845. - https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O15948/

chair-unknown/

chair-unknown/

Fig. 8: Embroidery pattern for a bird of paradise, Hertz and Wegener, Berlin, ca. 1860. - https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/

O132137/design-for-berlin-woolwork-embroidery-design-hertz-and-wegener/

O132137/design-for-berlin-woolwork-embroidery-design-hertz-and-wegener/

Fig. 9: Embroidery pattern for a dog chasing a bird, published by Wittich, Grunthal and Nicolai, Berlin, second half of the 19th century. - https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/

O567618/print-unknown/

O567618/print-unknown/

Fig. 10: The Last Supper, embroidery in Berlin wool work based on the painting by Leonardo da Vinci, 1851. - https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O314882/the-last-supper-needlework-picture/

Looking at the developments described above as a whole, it is clear that the boom in Berlin wool work embroidery was a major factor in the fact that almost all embroidery until the last quarter of the 19th century was done in cross-stitch or tapestry stitch (half cross-stitch), meaning that the embroidery techniques used were significantly reduced compared to the past. Berlin wool work, together with the content of 19th-century needlework lessons, contributed to embroidery being understood as almost synonymous with cross-stitch embroidery.

Berlin wool work attracted a great deal of criticism as early as the second half of the 19th century. This will be discussed in the following chapter. Despite all the criticism, however, one should not forget the perspective of the women who made embroidery according to Berlin patterns. The embroidery patterns themselves and their implementation in cross-stitch made it easier for women of all social classes to take up embroidery.[64] Even if they did not have considerable financial resources, embroidery enabled them to create something they found beautiful and with which they could decorate their homes. They could produce something that was neat and clean and met the standards of the craft. If, at the same time, they contributed to the family's reputation or supplemented the family budget by selling embroidery, this was something the women could be proud of. The fact that women from all walks of life produced "Berlin wool work" also boosted women's self-esteem. They did not have to settle for something that was inferior to the upper classes, but could present their embroidery with their heads held high, helped by the fact that they used the relatively simple technique of cross-stitch.

Berlin wool work attracted a great deal of criticism as early as the second half of the 19th century. This will be discussed in the following chapter. Despite all the criticism, however, one should not forget the perspective of the women who made embroidery according to Berlin patterns. The embroidery patterns themselves and their implementation in cross-stitch made it easier for women of all social classes to take up embroidery.[64] Even if they did not have considerable financial resources, embroidery enabled them to create something they found beautiful and with which they could decorate their homes. They could produce something that was neat and clean and met the standards of the craft. If, at the same time, they contributed to the family's reputation or supplemented the family budget by selling embroidery, this was something the women could be proud of. The fact that women from all walks of life produced "Berlin wool work" also boosted women's self-esteem. They did not have to settle for something that was inferior to the upper classes, but could present their embroidery with their heads held high, helped by the fact that they used the relatively simple technique of cross-stitch.