Embroidery and Cross-stitch in the 20th Century and Today

Even though the 20th century began with the avant-garde style of the Arts and Crafts Movement and Jugendstil/Art Nouveau in terms of embroidery, the Berlin Wool Work style and embroidery derived from school samplers clearly remained popular among the general population.

The example of the decorative kitchen towels, which could be found in an extraordinary number of households, shows that neither the embroidery motifs nor the social implications had changed significantly compared to the 19th century. The decorative kitchen towels had “ ihre Blütezeit […] zwischen 1870 und 1930. Vor allem in den Küchen vieler Haushalte waren sie aber noch bis in die 1950er Jahre hinein oft zu finden.”[1] Many of these towels were no longer hand-embroidered, but could be purchased either as printed templates or already machine-embroidered.[2] I remember that in my grandparents' kitchen in the 1950s, a blue embroidered kitchen towel was used to cover the dish towels and aprons that were hung on hooks. Like many other things in our family, our tablecloth was hand-embroidered in cross-stitch. Here, the tablecloth served a useful function as well as an aesthetic one, as the embroidery made the kitchen look prettier. I can't remember whether our towel had an embroidered saying on it. It may not have had a saying, but only ornamental embroidery, which may have been because my grandmother was the only married woman in a household of five girls, all of whom were very emancipated for the first half of the 20th century (even though they did a lot of needlework). As working women, they may have found the usual sayings that “Ordnungssinn, Fleiß, Sauberkeit, Kochkunst, Sparsamkeit, frohe Pflichterfüllung, etc. - priesen bzw. forderten oder gar die beschränkte Häuslichkeit als den natürlichen Lebensbereich der Frau betonten und lobten”[3] rather out of place. In general, however, the sayings on the dish towels and thus the towels themselves also had a normative function, especially “als die vorher durch Dienstboten verrichtete Hausarbeit allmählich von der bürgerlichen Hausfrau übernommen wurde”[4] This process began at the turn of the century and continued until 1930. The reasons for this were certainly the obligation imposed on employers since 1914 to pay into the insurance system for their servants, as well as the fact that there was now servant training, which enabled trained workers to seek positions in well-paying households, i.e., upper-class households.[5] The fact that in many households the housewife now had to do all the housework did not lead to her being valued more highly, but rather the stigma of the servant tended to be transferred to the housewife.[6] It was left to the sayings on the dish towels to remind the housewife of her destiny and ennoble her activities.

Fig. 1: Kitchen towel, embroidered according to a printed template, around 1900. The inscription says: "Don't look too far for happiness. It lies in domesticity."- https://westfalen.museum-digital.de/object/36176

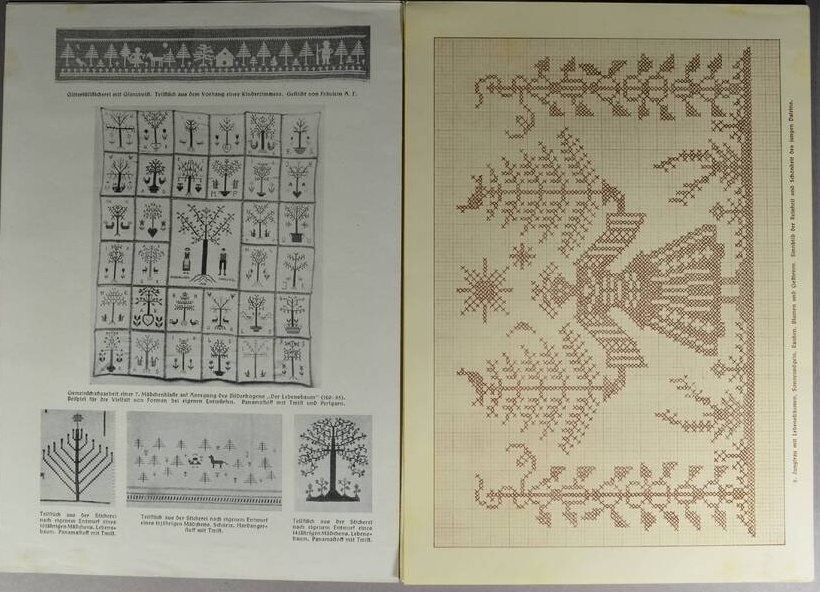

The more or less subtle role of embroidery in educating people about a worldview was exploited even more during the Third Reich. National Socialism was concerned with developing “Strategien zur Politisierung des Privaten und [der] Einflussnahme von Partei und Staat auf die familiäre Sphäre.”[7] Embroidery, which was taught in girls' handicraft lessons from the second year of school onwards, served this purpose. Together with sewing, knitting, crocheting, knotting, braiding, and weaving, it was used to teach girls skills that would be “später in ihrer Rolle als Mutter und Ehefrau vermehrt und unausweichlich zukommen [auf sie] zukommen würden.”[8] The foreword to the 1935 exhibition “Stickerei und Spitzen“ stated that the aim was “dem wiedererstandenen deutschen Volke die köstlichen Schätze seiner Heimat und Vergangenheit zu zeigen.”[9] Embroidery was “ein Teil wahrhaft deutschen Schaffens.”[10] The aim was to encourage “Nacheiferung in der Handarbeit.”[11] What was to be embroidered was determined by a publication entitled “Gestickte Sinnbilder. Eine Sammlung deutscher Sinnbilder für Kreuzstichstickerei bearbeitet von Christel Wöhrlin”[12] which appeared in 1937/1938. The booklet contains cross-stitch patterns on the themes of the tree of life, animals, humans and human works, as well as the sun and stars. The Documentation Center Nazi Party Rally Grounds refers to the accompanying text to the embroidery patterns, which unfortunately is not legible in the digitized version, emphasizing that the patterns are “nicht einfach […] naturgetreue Nachbildung[en] von Bäumen, Sternen oder einem Weinstock”[13] but that the patterns, as “Neubearbeitungen alter Zeichen ´an jenen ewigen Urgrund mahnen [sollten], dem wir alle entstammen: an die große Gemeinschaft des Blutes´.”[14] They were meant to “eine Glaubenswelt sichtbar und wirksam werden lassen, die Kinder und Kindeskinder zu einer gleichen Einordnung ihres Lebens in ewige Zusammenhänge [zu erziehen].”[15] It is probably no coincidence that the “Gestickte[n] Sinnbilder” contained patterns that were embroidered in cross-stitch. As already shown in the previous chapters, cross-stitch had long since established itself as the standard embroidery technique and was also primarily taught in needlework classes. Cross-stitch patterns were therefore particularly suitable for reaching every woman and subtly spreading the intended messages of Nazi ideology.

Fig. 2: Double page with embroidery patterns from

Gestickte Sinnbilder. Eine Sammlung deutscher Sinnbilder für Kreuzstichstickerei bearbeitet von Christel Wöhrlin, hrsg. von Christel Wöhrlin, veröffentlicht von Hans-Friedrich Munich 1937-1938.- https://skd-online-collection.skd.museum/Details/Index/6183477#

Gestickte Sinnbilder. Eine Sammlung deutscher Sinnbilder für Kreuzstichstickerei bearbeitet von Christel Wöhrlin, hrsg. von Christel Wöhrlin, veröffentlicht von Hans-Friedrich Munich 1937-1938.- https://skd-online-collection.skd.museum/Details/Index/6183477#

The outbreak of war and the intensification of Allied air raids on German cities probably meant the end of embroidery for many women, because “ für weibliche Handarbeiten war(en) in den Notzeiten weder Gelegenheit noch Interesse.”[16] Even after the war, most women probably had no opportunity to engage in embroidery. When needlework was done, it was probably not primarily for decorative purposes, but rather for practical items such as knitted socks, sweaters, jackets, etc., if it was even possible to obtain the materials for needlework. Many women also had a double burden: as war widows they had to work for the family´s livelihood and they had tp take care of children and the household. In general, women's employment increased after the war, and it is questionable how much time, in addition to financial problems and procurement problems, remained for non-essential handicrafts. The so-called Wirtschaftswunder of the 1950s changed this situation, and at least in wealthier circles, embroidery experienced a revival, as DIE ZEIT described somewhat ironically in 1962 when it said that they "doch die gleichen Muster nach(stickten), über denen ihre Urgroßmütter ihren Freiheitsdurst, ihre Leidenschaft oder nur ihre Langeweile zu vergessen suchten: Rosenranken, Blumenbuketts, Leiern im Lorbeerkranz."[17] The implication is that these ladies embroidered to repress the past in favor of the good old days. This attitude, as well as the type of patterns, were certainly the main reasons why embroidery was absolutely frowned upon in my youth in the 1960s. For the 1968 generation, embroidery, especially in public, was a sign of rebellion against their parents' failure to come to terms with the Nazi past and their return to pre-war values. Embroidery only made a brief comeback at the very end of the 1960s with the hippie movement as a “Symbol für Liebe, Frieden, Farben, Leben oder auch Ablehnung des Materialismus.”[18]

This development is also reflected in the development of needlework classes. Until the 1950s, skills such as sewing, darning, knitting, etc. had to be taught because “Kleidung hatte bis dahin [i.e. dem Beginn der Massenproduktion von Kleidung in den 1950er Jahren] einen hohen Wert und Beschädigtes musste ausgebessert werden”[19] which also explains why many women earned their living in textile professions. During those years, seamstresses came to the house and made clothes for the family. Handicraft lessons were a natural part of elementary school education, which also included learning embroidery stitches. Although sampler were no longer made as they had been before World War II, smaller embroidery projects were undertaken to demonstrate that there was also a practical purpose. The teaching objectives were to educate pupils in “Fleiß und Ausdauer, Ordnung und Genauigkeit, Sauberkeit und Sparsamkeit, zum Dienst in der Gemeinschaft.”[20] I myself had lessons that included needlework until the 8th grade of high school. The “crowning glory” of the lessons was sewing an apron with a machine. Unfortunately, I can no longer remember the name of the school subject. Until at least 1969, when I graduated from high school, some high schools offered a branch spezialized in education for domestic tasks, although the high school diploma obtained there did not qualify students for university study.[21] It can be compared to today's university for applied science entrance qualification.

Fig. 3: Exercise on different embroidery stitches, done by me in my third year of elementary school. The embroidery was lined on the back and a soft cloth was sewn in so that the piece could serve as a needle case (own photo)

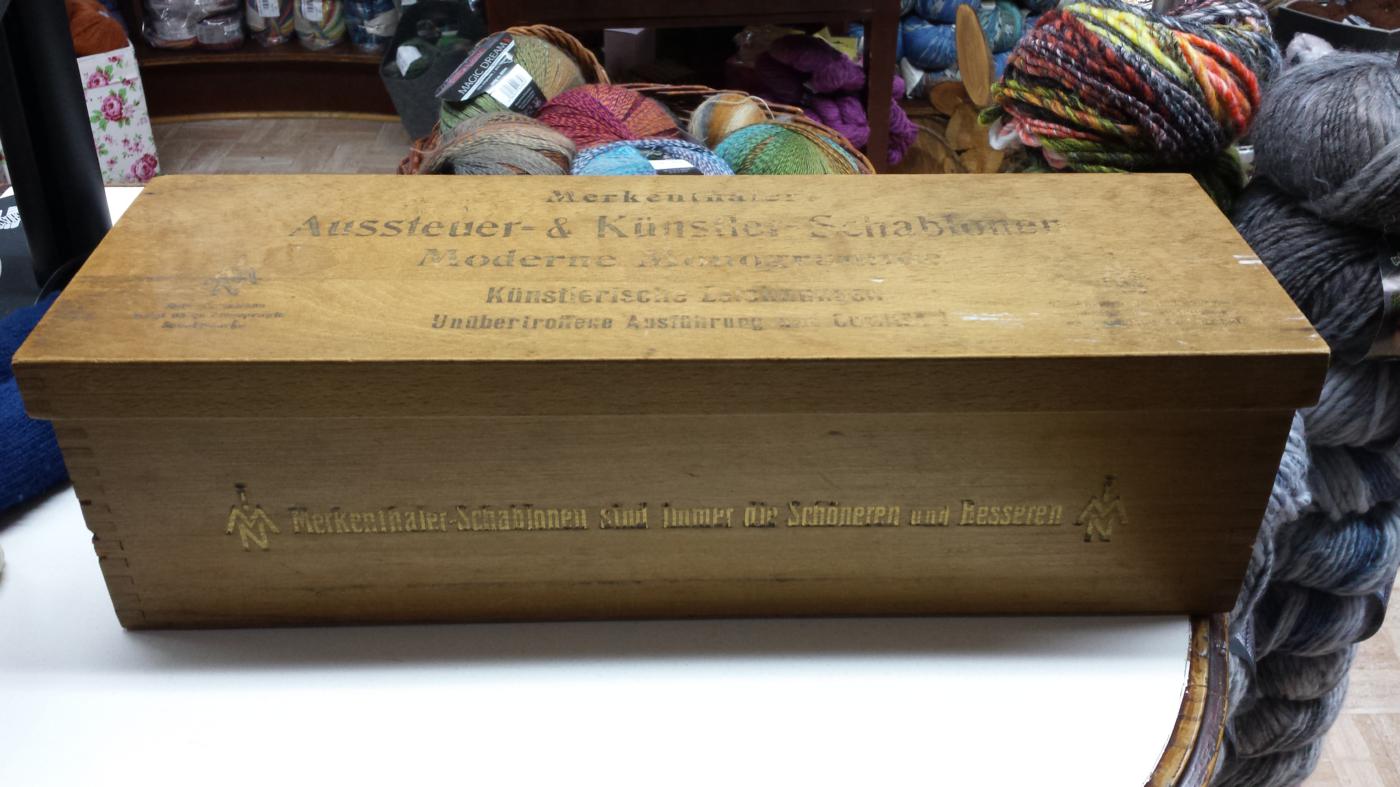

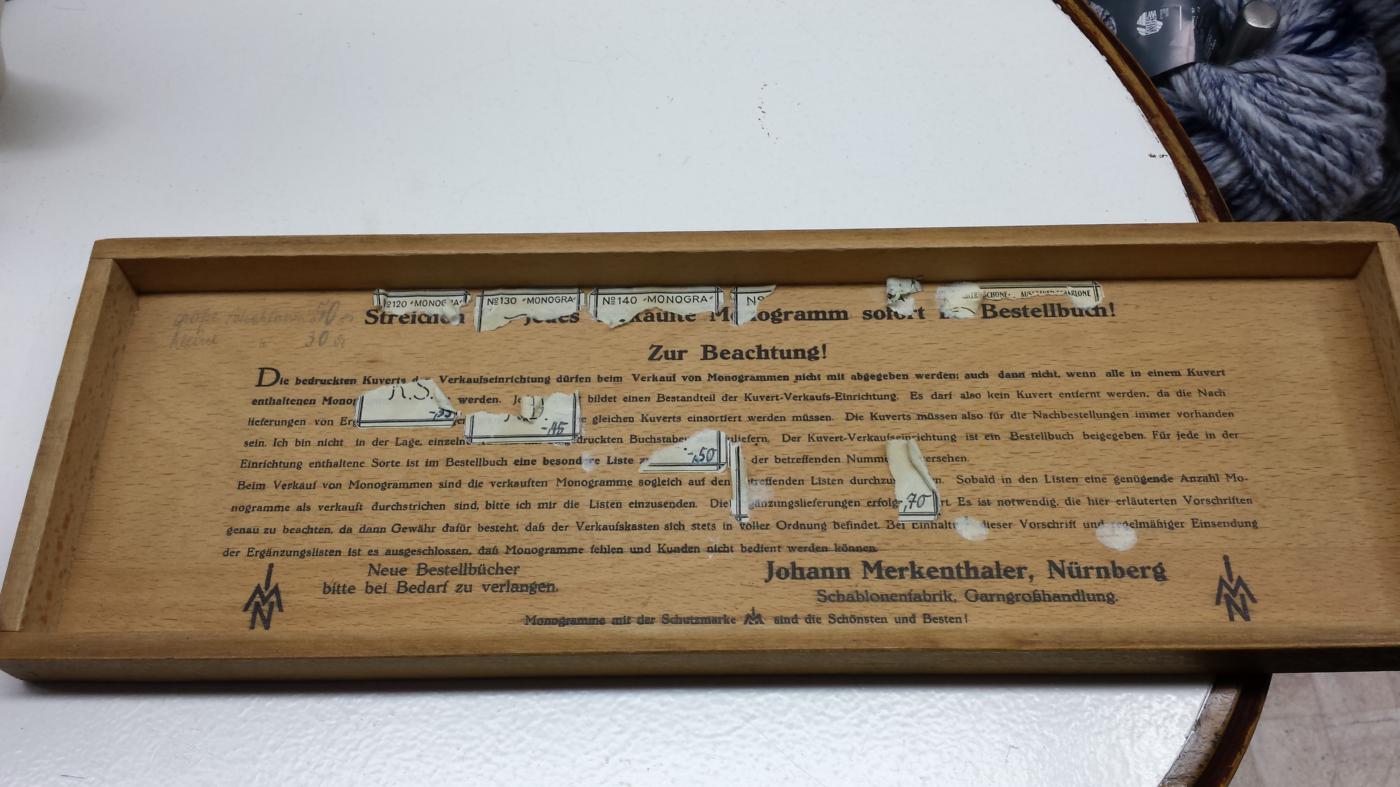

After the end of World War II, there was also the profession of embroiderer. Unfortunately, not much is known about this either. However, I remember that there was an embroidery workshop in my hometown with several employees and a retail store. You could generally order embroidery there, but you could also have monograms added to handkerchiefs, table linen, bed linen, etc., or have holes in tablecloths or bed linen darned. Such darned areas were no longer visible after the work ewas done. Among my current circle of acquaintances, there is a lady who trained as an embroiderer in a local company. She also reports that she performed the aforementioned activities. The demand for such services probably declined after washing machines became commonplace in households in the 1960s and it was no longer necessary to use a bleach, making monogramming unnecessary. In 2011, the previously separate apprenticeship professions of embroiderer, weaver, knitter, etc. were combined into a new apprenticeship profession of textile designer in the craft sector, specializing in embroidery/knitting/weaving/felting/trimmings/bobbin lace.[22]

Fig. 4: Box with embroidery templates from the Johann Merkenthaler company for monogram embroidery. This box was kept in the handicrafts house in Meschede. The templates were still used in the 1950s for training as an embroiderer (own photo).

Fig. 5: Inside of the lid of the template box (own photo).

Fig. 6: Embroidery templates for monogram embroidery (own photo).

In general, embroidery has regained importance since the 1990s, but increasingly since the COVID-19 pandemic. Several aspects can be noted here.

Embroidery is repeatedly mentioned in connection with a movement that focuses on promoting mental health. It can play a role “beim Abbau von Stress und Angstzuständen und bei der Bewältigung von Trauer oder Traumata.”[23] Various effects of the therapeutic use of hand embroidery are mentioned, such as practicing mindfulness, promoting creativity through new forms of expression and experimentation with techniques and materials, practicing patience and achieving long-term goals, developing planning skills, improving fine motor skills, strengthening self-confidence and self-esteem through successful work, and achieving a better work-life balance.[24]

Embroidery is repeatedly mentioned in connection with a movement that focuses on promoting mental health. It can play a role “beim Abbau von Stress und Angstzuständen und bei der Bewältigung von Trauer oder Traumata.”[23] Various effects of the therapeutic use of hand embroidery are mentioned, such as practicing mindfulness, promoting creativity through new forms of expression and experimentation with techniques and materials, practicing patience and achieving long-term goals, developing planning skills, improving fine motor skills, strengthening self-confidence and self-esteem through successful work, and achieving a better work-life balance.[24]

It is also emphasized that embroidery is a practice of relaxation and serenity and helps to disconnect from stress, at least temporarily.[25] A significant advantage of using embroidery as a professional therapy is that it can be easily adapted to the different needs of patients by choosing from a variety of more or less complicated embroidery techniques and applying both simple and complex patterns.[26]

The use of embroidery to promote mental health seems to me to be linked to a development that began in England in 1918 with the founding of the Bradford Khaki Handicrafts Club and, also in 1918, with the founding of the Disabled Soldiers' Embroidery Industry.[27] These were typical English charities that cared for veterans of the British armed forces who had returned from the World War with physical and/or psychological injuries and were now threatened with incapacity to work, impoverishment, and hardship. They were offered the opportunity to learn embroidery, which was considered a female activity.[28] The Disabled Soldiers' Embroidery Industry produced “regimental colors, sheriff and guild banners, embroideries for fashionable dress and historic furniture, ecclesiastical designs, [...] and other commissions for original designs and copies after antique needlework, tapestries, and maps.”[29] Their works were shown at various exhibitions and became very well known, mainly through the patronage of members of the royal family and the commissions they placed. It is reported that the veterans' work contributed to “the ‘modern craze’ for needlework in the interwar years.”[30] The therapeutic benefits of embroidery for veterans have not been proven in detail. However, it has been reported that embroidery brought joy to the soldiers and that “in several cases the health of the workers has visibly improved.”[31] It was also an opportunity to overcome the isolation associated with long periods of convalescence, during which visits from relatives were almost impossible. The same activity also brought together soldiers who were connected by similar impairments and strengthened their sense of belonging to a group.[32] The fact that the veterans earned some money from embroidery also helped to counteract feelings of uselessness and gain self-esteem because they were able to contribute to the family income.[33] In this respect, the income generated from embroidery was a means of helping them to help themselves.[34] It is not known how long the Bradford Khako Handicrafts Club existed; te Disabled Soldiers´ Embroidery Índustry ceased operations in 1955. Some of the veterans trained there continued to sell or exhibit theit work until 1968.[35]

The use of embroidery to promote mental health seems to me to be linked to a development that began in England in 1918 with the founding of the Bradford Khaki Handicrafts Club and, also in 1918, with the founding of the Disabled Soldiers' Embroidery Industry.[27] These were typical English charities that cared for veterans of the British armed forces who had returned from the World War with physical and/or psychological injuries and were now threatened with incapacity to work, impoverishment, and hardship. They were offered the opportunity to learn embroidery, which was considered a female activity.[28] The Disabled Soldiers' Embroidery Industry produced “regimental colors, sheriff and guild banners, embroideries for fashionable dress and historic furniture, ecclesiastical designs, [...] and other commissions for original designs and copies after antique needlework, tapestries, and maps.”[29] Their works were shown at various exhibitions and became very well known, mainly through the patronage of members of the royal family and the commissions they placed. It is reported that the veterans' work contributed to “the ‘modern craze’ for needlework in the interwar years.”[30] The therapeutic benefits of embroidery for veterans have not been proven in detail. However, it has been reported that embroidery brought joy to the soldiers and that “in several cases the health of the workers has visibly improved.”[31] It was also an opportunity to overcome the isolation associated with long periods of convalescence, during which visits from relatives were almost impossible. The same activity also brought together soldiers who were connected by similar impairments and strengthened their sense of belonging to a group.[32] The fact that the veterans earned some money from embroidery also helped to counteract feelings of uselessness and gain self-esteem because they were able to contribute to the family income.[33] In this respect, the income generated from embroidery was a means of helping them to help themselves.[34] It is not known how long the Bradford Khako Handicrafts Club existed; te Disabled Soldiers´ Embroidery Índustry ceased operations in 1955. Some of the veterans trained there continued to sell or exhibit theit work until 1968.[35]

Fig. 7: Mother Goose Embroidery, Museum of Cambridge. The embroidery was made by a soldier wounded in Word War I. The inspiration for the motif probably comes from Charles Perraut´s fairy tale book „Hitstoires ou contes du temps passes, avec de motalites“, published in 1695, which appeared in English translation as „Histories of Tales of Past told by Mother Goose“ in England in 1729.- https://www.museumofcambridge.org.uk/2024/04/coping-through-stitch-soldiers-recovering-in-hospital-and-the-embroideries-that-passed-the-time/

Fig. 8: Altar Cloth for Bradford Cathedral, made by soldiers from the Khaki Handicraft Club.- https://trc-leiden.nl/trc-needles/organisations-and-movements/charities/bradford-khaki-handicrafts-club

Fig. 9: Altar cloth for St. Paul´s in London made by soldiers from the Disabled Soldiers´ Embroidery Industry.- https://www.flickr.com/photos/stpaulslondon/albums/

72157645431808070/with/14693469866

72157645431808070/with/14693469866

The English charity Fine Cell Work, founded in 1995, appears to be directly in line with the aforementioned initiatives. Volunteers from Fine Cell Work teach embroidery in prisons to enable inmates to spend their time in prison meaningfully and also earn some money.[36] By 2025, 2,000-3,000 prisoners had participated in the project,[37] and in 2017, 96% of the prisoners participating in 32 English prisons were male. They mainly produce cushions and Christmas decorations, which are sold throughout England.[38] Fine Cell Work also pursues the therapeutic goals mentioned in the previous paragraph. The prisoners, it is reported, appreciate the occupation and gain self-esteem through their work, which seems to be more important to them than the earnings.[39] The work gained widespread recognition through its inclusion in an exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum[40] and through its participation in the “Magna Carta” project by artist Cornelia Parker, who was commissioned by the Ruskin School of Art to create a 13-meter-long embroidery to mark the 800th anniversary of the Magna Carta of 1215.[41] In addition to the effects on mental health, the work of Fine Cell Work has shown that embroidery also has positive effects on physical health, as it can lower blood pressure and pulse rate. In addition to the effects on mental health, Fine Cell Work's work has shown that embroidery also has positive effects on physical health, as embroidery can lower blood pressure and pulse rate[42] and reduce the risk of dementia, as studies have now shown.[43]

Fig. 10: Fine Cell Work, cushion with wool and cotton embroidery on wool. The motif is inspired by the illustrations of cartoonist J.J. Grandville for “Scènes de la Vie Privée et Publique des Animaux,” in which anthropomorphized animals depicted human behavior in a satirical manner. The cushion is available from the Fine Cell Work online shop. - https://finecellwork.co.uk/collections/all-cushions/products/animaux-lioness-cushion?variant=43713918863

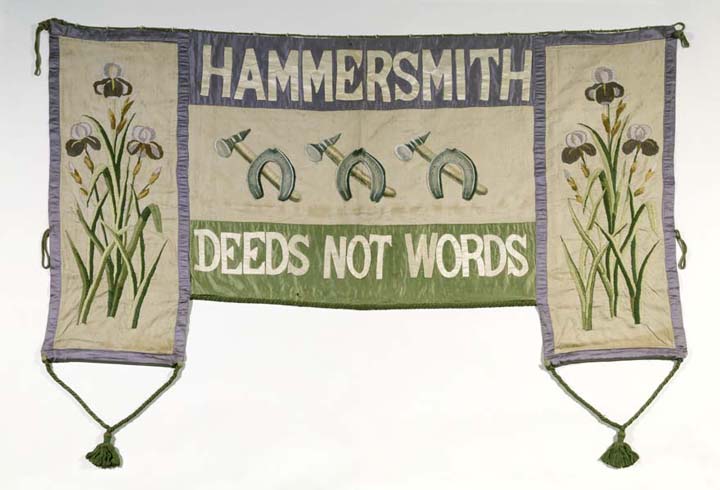

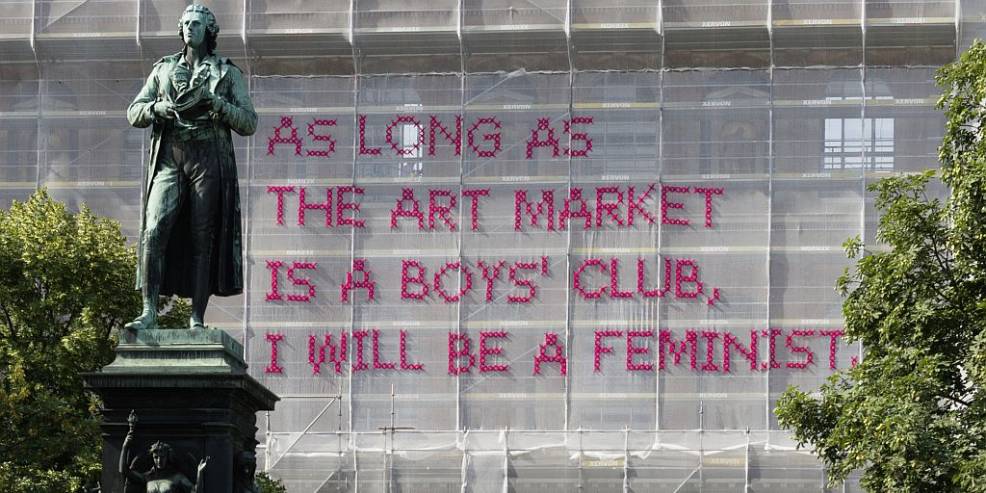

Since the beginning of the 21st century, embroidery has regained popularity as part of the so-called craftivism movement. This movement aims to combine craftsmanship and activism in order to spread political and social, often feminist, messages and bring supporters of these messages together into a community. The best-known example of craftivism is the knitted pussy hats worn by participants in the Women's March on January 21, 2017, to protest against the misogynistic attitude of the newly elected US President Donald Trump. This movement, which uses embroidery as a subversive tactic in our context, also ties in with similar approaches in history, such as Mary Stuart, who used her embroidery to send political messages. Another example from history is the embroidery of the Artists' Suffrage League, which embroidered over 150 banners between 1908 and 1913 that were carried during suffragette demonstrations and marches.[44] In the present day, well-known sayings are often provocatively distorted and integrated into embroidery.[45] Public exhibitions of such embroidery highlight the questionable nature of generally accepted beliefs or established behaviors and are capable of undermining them. The success of Sarah Corbett, who is committed to social justice, shows that such messages can not only change consciousness, but also achieve real success. She embroidered Marks & Spencer handkerchiefs with personal messages and gave them to the company's board members. The dialogue this initiated led to wage increases for the employees.[46]

Fig. 11: Banner of the suffragettes of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU), 1908.- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Suffragette_flag_

(United_Kingdom).svg#/media/File:Suffragette_Banner_-_Museum_of_London.jpg

(United_Kingdom).svg#/media/File:Suffragette_Banner_-_Museum_of_London.jpg

Fig. 12: Women´ March am 21.1.2017.- https://www.tagesspiegel.de/gesellschaft/was-es-mit-den-pussy-hats-auf-sich-hat-4088287.html

Much of today's embroidery that can be classified as craftivism overlaps with embroidery that is commonly classified as art.[47] In terms of their objectives in particular, these “works of art” often correspond to craftivism in that they address social and political issues. In the course of the creative process, "findet eine Rückbesinnung auf das traditionelle Kunsthandwerk statt. Im kreativen Prozess werden alte Techniken zeitgemäß adaptiert und neuartige Stickwerke [geschaffen].“[47] In the field of embroidery art, artists experiment with base materials, no longer embroidering only textile materials, but also “zum Beispiel Porzellan, Blech, Schiefer, Beton oder Erde”[48] or using embroidery threads in different ways by tying, new types of fastening, stretching, and the like.[49] Here, too, the aim of alienation is to create “neue Lesearten, die provokant, verwirrend oder auch amüsant wirken können”.[50]

Fig. 13: Katharina Cibulka, embroidered construction site tarpaulin, cross-stitch with pink tulle on construction site netting. The artist's aim with this embroidery, which is mounted in a male-dominated location, is to draw attention to feminist issues. - https://www.emma.de/artikel/fuer-mehr-feminismus-im-oeffentlichen-raum-335965

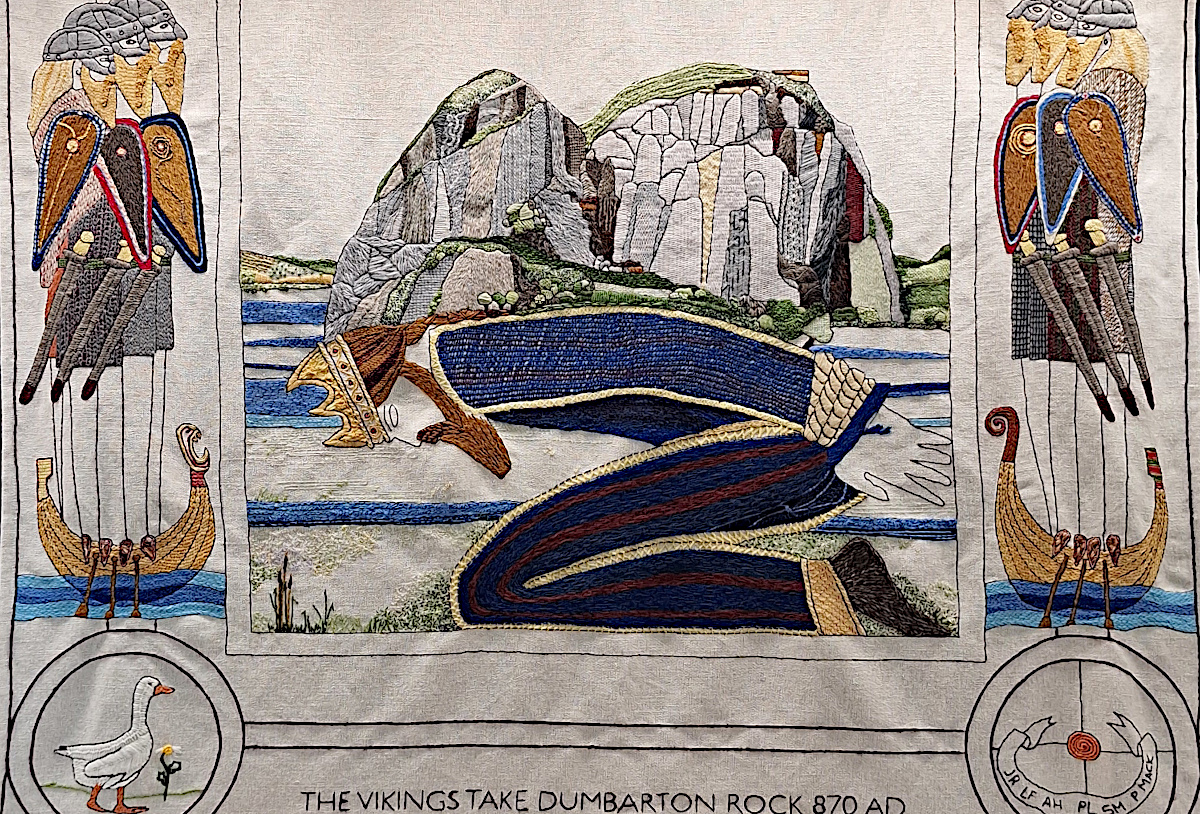

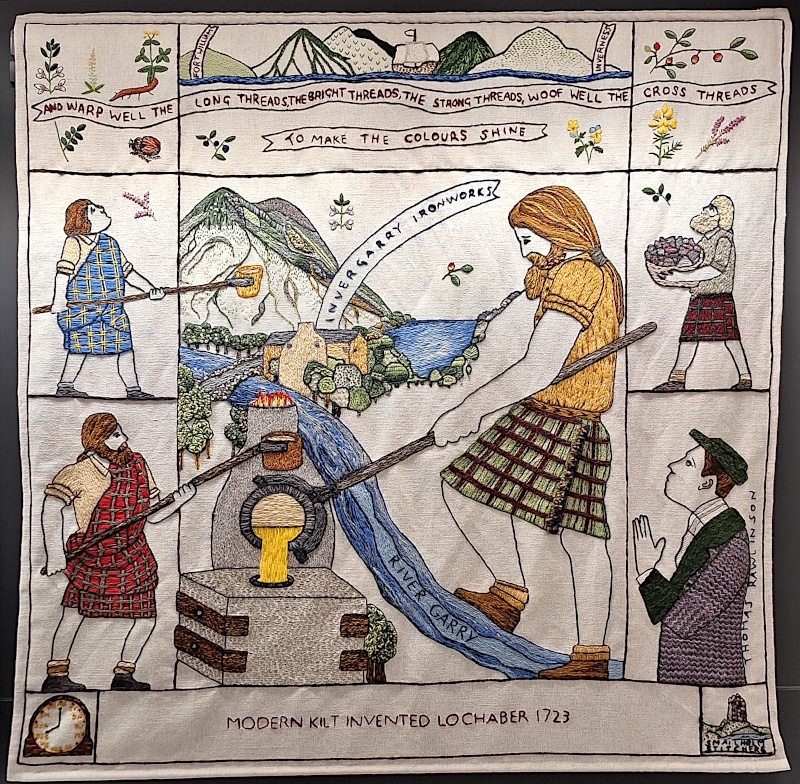

Even though embroidery has regained popularity in Germany since the turn of the 20th to the 21st century, the number of people who embroider in Germany is negligible compared to other countries. In Anglo-Saxon countries in particular, the number of embroiderers, companies that design and market embroidery patterns, websites dedicated to embroidery, etc. is disproportionately higher than in Germany.[51] There are large-scale projects such as the creation of the Great Tapestry of Scotland, an embroidery inspired by the Bayeux Tapestry that depicts 12,000 years of Scottish history. More than 1,000 people embroidered this collaborative work, which has artistic and craft value as well as community-building value.[52] Institutions such as the Royal School of Needlework, founded in 1872, or the tradition of charities, whose social commitment is based on the Protestant emphasis on charity, may play a role in the popularity of handicrafts – and thus also embroidery. As described above, they help people to help themselves by teaching skills and abilities that are useful in working life and empower the individual. The difference between the Anglo-Saxon tradition of embroidery and the German tradition is also reflected in the very different number of exhibitions in museums – exhibitions in England are particularly numerous – and in the number of objects that museums have digitized and made available to the public. Anglo-Saxon countries are also “ahead” in research, as evidenced by the number of English-language titles dealing with various aspects of embroidery.

Fig. 14: The conquest of Dumbarton Rock by the Vikings in 870, part of the Great Tapestry of Scotland, 2013.- https://www.textile-art-magazine.de/reportagen/bericht-ueber-die-ausstellung-der-great-scottish-tapestry-in-galashiels-schottland/

Fig. 15: The invention of the kilt, part of the Great Tapestry of Scotland, 2013. The modern kilt was first “invented” or developed in the 1720s by Thomas Rawlinson, a Quaker from Lancashire. Until then, the Scots wore the big kilt, a huge blanket that they wrapped around themselves and fastened with a wide belt. Rawlinson found that this garment hindered his workers and promoted the development of the “small kilt,” which looks much like the one we know today. - https://www.textile-art-magazine.de/reportagen/bericht-ueber-die-ausstellung-der-great-scottish-tapestry-in-galashiels-schottland/

Based on knowledge of English tradition and in view of the differences between Anglo-Saxon countries and Germany, the German Embroidery Guild was founded in 1998. It is dedicated to “der Erhaltung und Weiterentwicklung traditioneller Handarbeitstechniken wie der Handstickerei und anderer textiler Künste.”[53] It promotes “das Handwerk durch Vermittlung der Techniken und unterstützt kreative Entwicklungen auf dem Gebiet der Textilkunst.”[54] To this end, it has established a center of excellence for embroidery and offers embroidery courses and workshops, organizes exhibitions, and maintains an extensive library of specialist literature. In addition, it offers local meetings and the associated personal exchange as an opportunity to maintain and strengthen interest in embroidery.

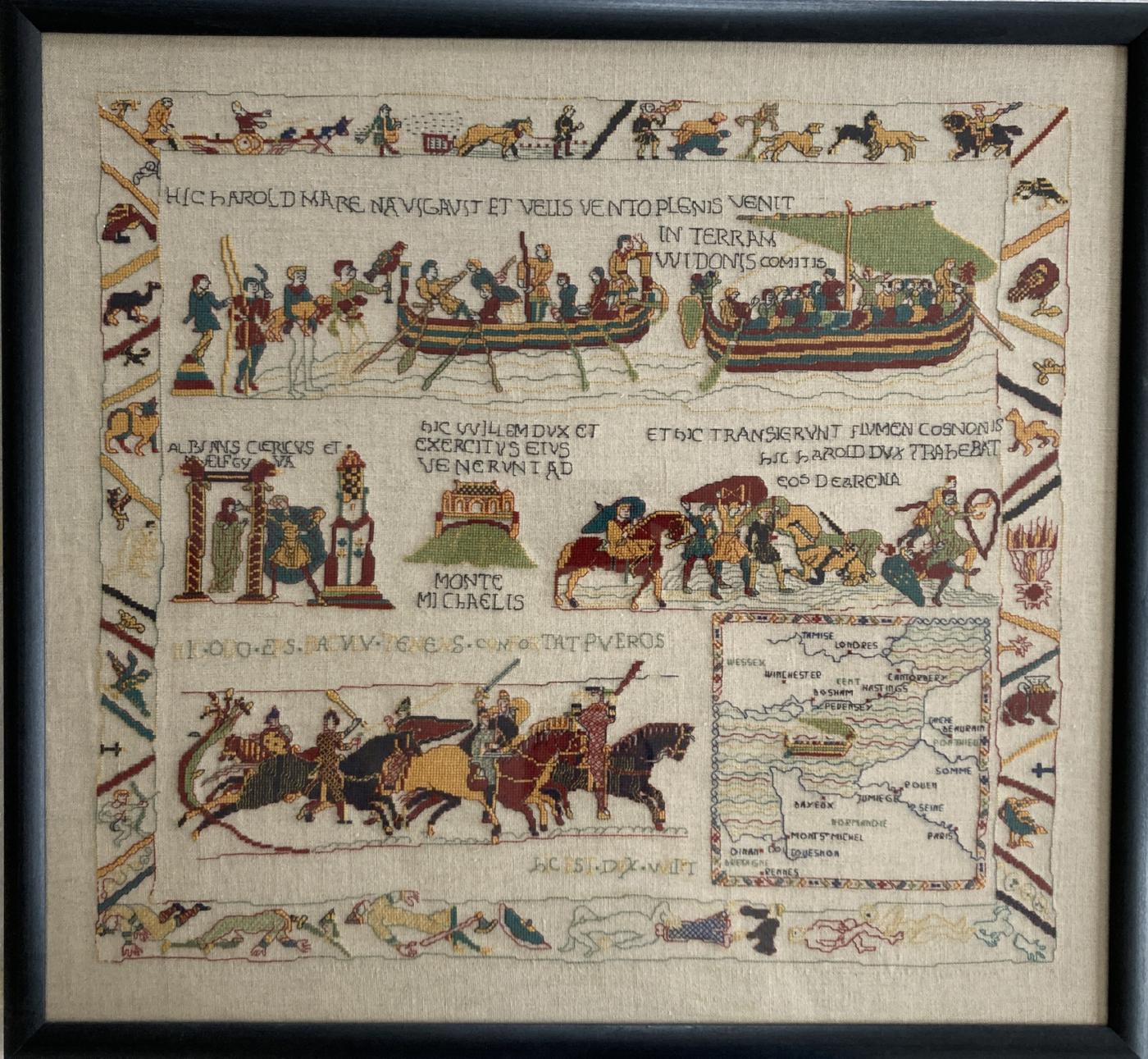

In general, embroidery is part of the do-it-yourself trend in Germany today. Embroidery is probably practiced in all social classes. The embroidery patterns consist of templates for pillowcases, tablecloths, table runners, bags, pouches for various items, clothing decorations, etc., and—in large numbers—templates for wall hangings. There are instructions for making embroidery for small gifts, such as tags for gift wrapping, Christmas decorations, small brooches, and the like.[55] The embroidery patterns themselves are designed as they have been since such patterns were first published in 1787: on pattern paper, the individual embroidery stitches are represented either by symbols or – predominantly – by colors plus symbols. The grid shows all 10 stitches in slightly bold print to make counting easier. The pattern comes with a legend that indicates which symbol/color corresponds to which color number from a specific manufacturer of embroidery thread. Conversion tables on the Internet or, very occasionally, as an appendix in an embroidery pattern book, make it possible to assign the color numbers to the colors of another manufacturer. Linen is usually used as the embroidery base, and cotton is the most commonly used embroidery material. Silk or wool are used less frequently. The embroidery motifs are so varied that it is impossible to list them all individually. Overall, however, there are very few motifs reminiscent of Berlin Wool Work embroidery – possibly because it was precisely these motifs that discredited embroidery as old-fashioned and frumpy since the 1970s. The embroidered pictures are particularly reminiscent of samplers in their design, in that the background is not embroidered and individual image elements are combined to form a whole, sometimes resembling the random or symmetrical arrangement of samplers, sometimes forming a narrative whole. In addition, there are embroidery patterns that translate historical embroidery into contemporary embroidery designs, allowing the historical embroidery to be reproduced in detail. By far the most common embroidery stitch is the cross stitch; according to my (unverified) estimate, 90% of all embroidery patterns are for cross stitch embroidery. The reason for this, apart from the historical development towards cross stitch, is probably that all other stitches require more complicated methods to transfer them onto the fabric.

In general, embroidery is part of the do-it-yourself trend in Germany today. Embroidery is probably practiced in all social classes. The embroidery patterns consist of templates for pillowcases, tablecloths, table runners, bags, pouches for various items, clothing decorations, etc., and—in large numbers—templates for wall hangings. There are instructions for making embroidery for small gifts, such as tags for gift wrapping, Christmas decorations, small brooches, and the like.[55] The embroidery patterns themselves are designed as they have been since such patterns were first published in 1787: on pattern paper, the individual embroidery stitches are represented either by symbols or – predominantly – by colors plus symbols. The grid shows all 10 stitches in slightly bold print to make counting easier. The pattern comes with a legend that indicates which symbol/color corresponds to which color number from a specific manufacturer of embroidery thread. Conversion tables on the Internet or, very occasionally, as an appendix in an embroidery pattern book, make it possible to assign the color numbers to the colors of another manufacturer. Linen is usually used as the embroidery base, and cotton is the most commonly used embroidery material. Silk or wool are used less frequently. The embroidery motifs are so varied that it is impossible to list them all individually. Overall, however, there are very few motifs reminiscent of Berlin Wool Work embroidery – possibly because it was precisely these motifs that discredited embroidery as old-fashioned and frumpy since the 1970s. The embroidered pictures are particularly reminiscent of samplers in their design, in that the background is not embroidered and individual image elements are combined to form a whole, sometimes resembling the random or symmetrical arrangement of samplers, sometimes forming a narrative whole. In addition, there are embroidery patterns that translate historical embroidery into contemporary embroidery designs, allowing the historical embroidery to be reproduced in detail. By far the most common embroidery stitch is the cross stitch; according to my (unverified) estimate, 90% of all embroidery patterns are for cross stitch embroidery. The reason for this, apart from the historical development towards cross stitch, is probably that all other stitches require more complicated methods to transfer them onto the fabric.

Fig. 16: Cross-stitch embroidery on linen. This embroidery is an example of a modern sampler, 2017 (own embroidery, own photo)

Fig. 17: Example of cross-stitch embroidery alluding to a story, in this case Hans Christian Andersen's fairy tale “The Little Match Girl,” 2020 (own embroidery, own photo)

Fig. 18: Example of cross-stitch embroidery with cotton thread and metallic thread on linen, 2018 (own embroidery, own photo)

Fig. 19: Depiction of a nostalgic market scene, example of cross-stitch embroidery with contoured edges, 2023 (own embroidery, own photo)

Fig. 20: Scenes from the Bayeux Tapestry, embroidered in cross-stitch based on a French pattern. The map is a modern addition to the embroidery pattern, wool on linen, 2021 (own embroidery, own photo)

With regard to all of the above aspects, contemporary hand embroidery is based on developments that have taken place since the Renaissance. Part of thr motivation for embroidery might be the wish to keep a traditional handicraft alive, although embroidery has become much easier than in former times. Nowadays, it is no longer necessary to practice embroidery stitches or patterns on samplers or to pass them on through them. Embroidery is no longer part of the education and training of girls, nor does embroidery serve to prove a young lady's marriageability. Nor is it an expression of social status. Rather, embroidery today is a leisure activity based on personal preference.