Embroidery in the High and Late Middle Ages

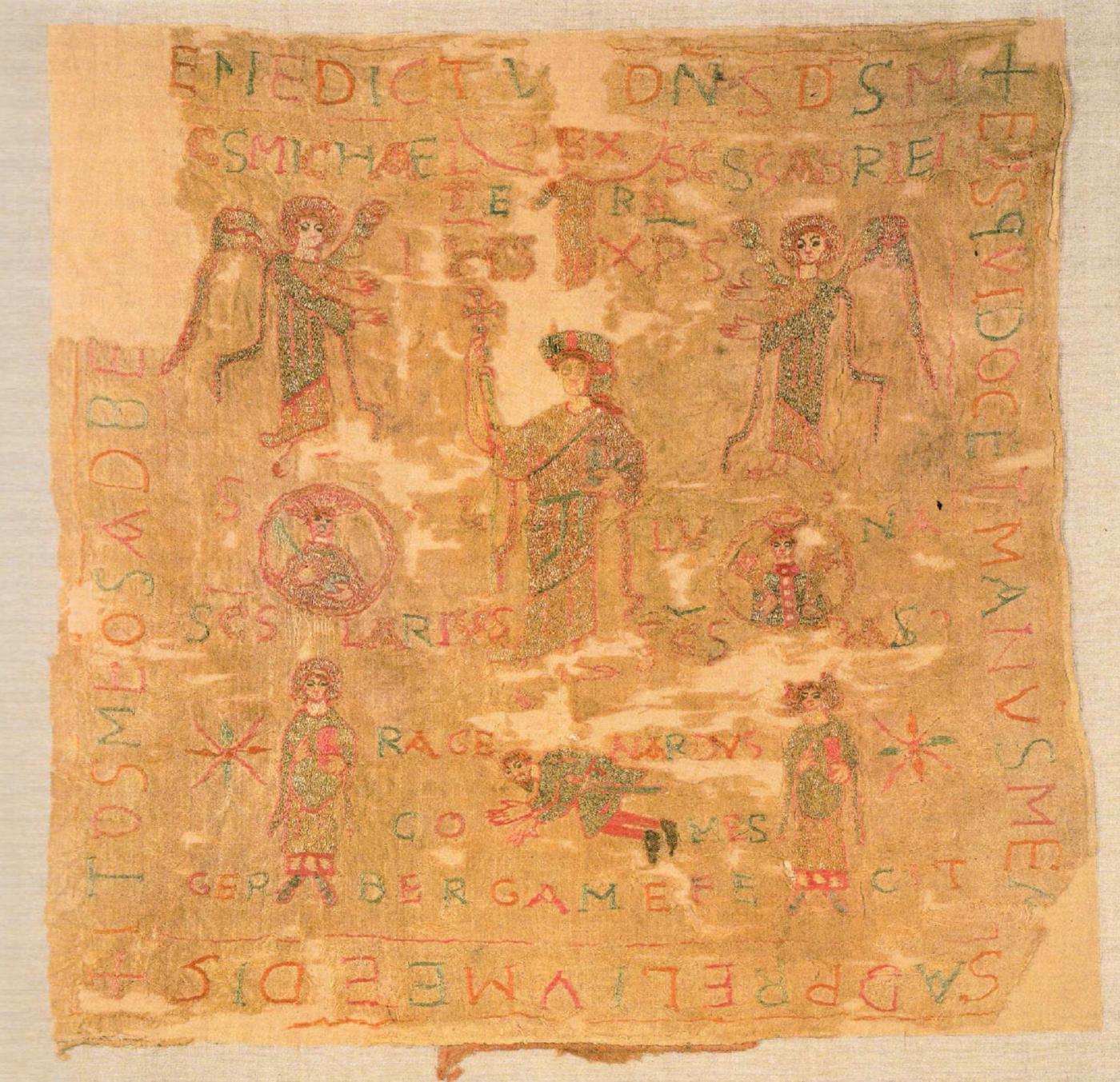

Around/after 957, the so-called war banner of Queen Gerberga (913-968), a sister of Emperor Otto I, was created. The embroidery shows Christ with a cross staff in the center. At his feet is a figure identified in the embroidered text as "Ragenardus Comes." A more precise dating of the embroidery depends on the identification of this Ragenardus. One interpretation identifies him as Gerberga's nephew, Count Reginar III (+973). Gerberga was first married to Duke Giselbert of Lorraine. From 955 onwards, her nephew Reginar attempted to regain the ducal position in Lorraine, thereby antagonizing not only Emperor Otto I's brother, Archbishop Bruno of Cologne, who held the ducal title after Giselbert's death, but also King Lothar of France, Gerberga's son from her second marriage to Louis IV, King of West Francia. The war lasted from 955 to 957, with Reginar suffering a crushing defeat and being banished to Bohemia by Otto I in 958[1] . According to this interpretation, the embroidery would have been created between 955 and 957, as the flag would have served as a war flag during the conflict. A retrospective documentation of the victory, as Böse considers possible[2] , seems rather unlikely, since Reginar, kneeling at the feet of Christ, is still depicted wearing his sword. Since he would have had to lay down his sword after his defeat, the flag could be dated to around 956, when Reginar's position in the conflict had already deteriorated, so that his submissive posture could indicate his impending defeat and, in view of this, the flag was intended to motivate his opponents to redouble their efforts.

It is precisely the depiction of the count submitting to Christ with his sword that leads Fraser McNair to a different identification and thus interpretation of the flag. He believes the count to be Ragenold (Rainald) de Roucy, who undertook military expeditions to Burgundy in the late 950s together with Gerberga and Bruno of Cologne. Supported by the words of Psalm 144 embroidered on the edge of the flag, McNair assumes that the flag depicts the successful warrior Ragenold, who may have received it as a gift[3] .

Yet another explanation can be found in Alexandra Gajewskia and Stefanie Seeberg, who see the figure as the aforementioned Reginar. His depiction shows the "traditional humble attitude of worship adopted by patrons on donor images."[4] However, given the hostile relationship between Reginar and Gerberga, it seems rather unlikely that Gerberga could have embroidered the flag on Reginar's behalf.

Whichever interpretation one tends towards, the embroidery on the flag seems to bear witness to a specific historical event that took place between 955 and 957, making the dating plausible. In any case, the creation of the embroidery can be narrowed down to the period between 955 and 968, as the embroidered text notably and explicitly names the maker of the embroidery, stating "Gerberga me fecit." The embroidery is executed in split stitch and gold embroidery using the appliqué technique[5].

Yet another explanation can be found in Alexandra Gajewskia and Stefanie Seeberg, who see the figure as the aforementioned Reginar. His depiction shows the "traditional humble attitude of worship adopted by patrons on donor images."[4] However, given the hostile relationship between Reginar and Gerberga, it seems rather unlikely that Gerberga could have embroidered the flag on Reginar's behalf.

Whichever interpretation one tends towards, the embroidery on the flag seems to bear witness to a specific historical event that took place between 955 and 957, making the dating plausible. In any case, the creation of the embroidery can be narrowed down to the period between 955 and 968, as the embroidered text notably and explicitly names the maker of the embroidery, stating "Gerberga me fecit." The embroidery is executed in split stitch and gold embroidery using the appliqué technique[5].

The textiles of the Bamberg Cathedral Treasury are particularly noteworthy examples of 11th-century embroidery. These are various objects belonging to Emperor

Henry II (*973/978 + 1024, emperor 1002-1024) and his wife Kunigunde (*975 +1033) as the patrons, all of which appear to have been created during the reign of

Henry II:

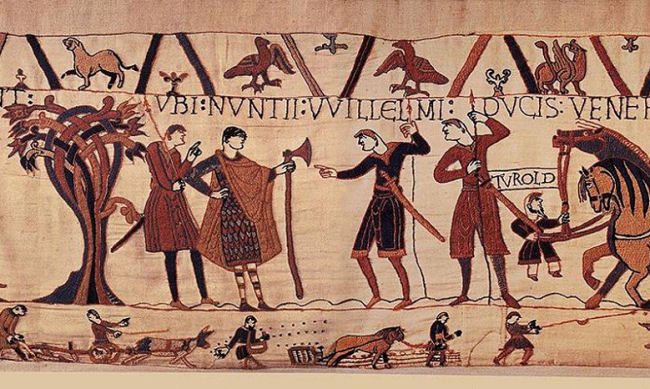

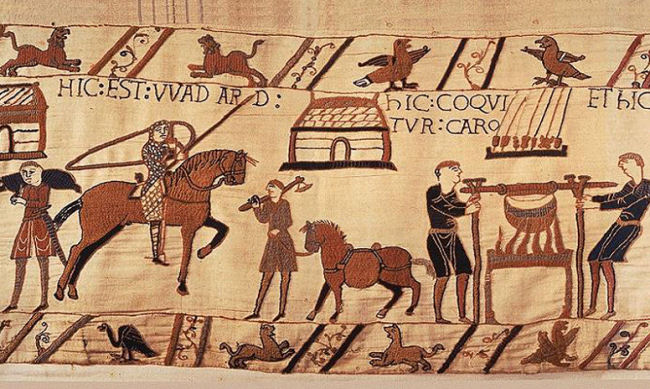

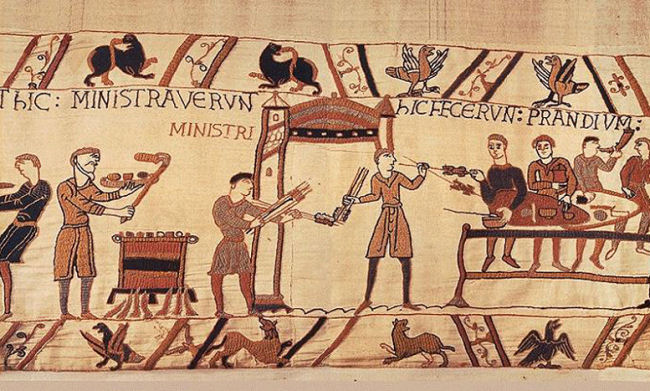

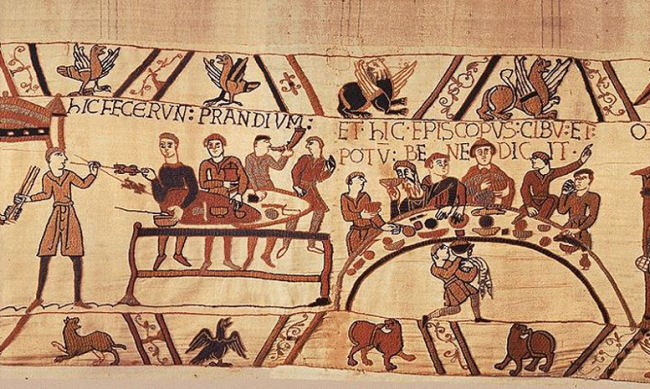

A secular embroidery that, like Gerberga's war banner, refers to a specific historical event is the famous Bayeux Tapestry. Nine linen panels, each approximately 50 cm high, are sewn together to form a tapestry over 70 m long depicting the conquest of England by William the Conqueror in 1066. In numerous individual scenes, accompanied by embroidered texts, the development is depicted from the decision of the English King Edward the Confessor to appoint the Norman Duke William, whose strict organization of his duchy he admired, as his successor in 1064, to his victory over his rival Harold Godwinson at the Battle of Hastings in 1066. The continuous depiction is framed at the top and bottom by borders showing animals, plants, fable scenes and mythical creatures, as well as scenes commenting on the plot, such as agricultural activities or details of a battle – wounded, dead, looting, etc.[8] . The layout of the embroidery follows the tradition of depicting secular events in Viking art, as fragments found in a Viking ship burial in Oseberg from the 8th or 9th century show[9] .

Contrary to earlier assumptions that William the Conqueror's wife, Matilda, had the tapestry made, research now believes that it was commissioned by Odo, Bishop of Bayeux, who was William the Conqueror's half-brother. He was bishop of Bayeux from 1049 to 1097; after the conquest of England, he was also Earl of Kent until 1088. " Diese Sichtweise wird gestützt durch die Tatsache, dass Odo in vier Szenen der Stickerei und dreimal in den Inschriften erwähnt wird […] und drei der neben den Hauptakteuren in den Inschriften benannten Personen, Wadard, Vital und Turold, die in keiner anderen zeitgenössischen Quelle der Schlacht bei Hastings genannt werden, […] sich auf Odo [beziehen]"[10]. If we follow this attribution of the patron, we can date the completion to 1077 at the latest, as it can be assumed that the tapestry was presented for the inauguration of Bayeux Cathedral.

Assumptions about where the embroidery was made vary depending on the nationality of the researchers. While French researchers assumed it was of French origin, English researchers assumed it was made in England. Nowadays, English provenance is generally accepted, with three main reasons being cited: "Zu dieser Zeit [gemeint: als Odo Graf von Kent war] gab es eine angesehene Schule für Stickerei in Canterbury […] und Stil und Technik des Teppichs deuten auf diese Schule hin. Außerdem sind Details in einer Reihe von Motiven deutlich von Illustrationen in angelsächsischen Handschriften aus dem 10. und 11. Jahrhundert"[11] and the orthographic forms of proper names in the Latin texts are strongly influenced by English[12] .

Henry II (*973/978 + 1024, emperor 1002-1024) and his wife Kunigunde (*975 +1033) as the patrons, all of which appear to have been created during the reign of

Henry II:

- the tunic of Henry II, sometimes also called the tunic of Kunigunde

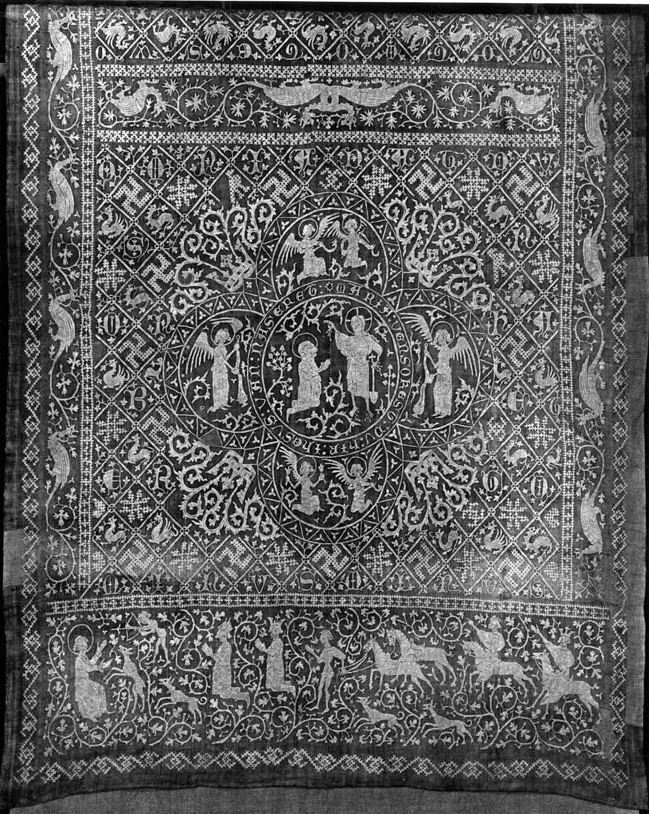

- the blue Kunigunde cloak, which is the oldest surviving liturgical garment with a surface-filling pictorial program

- Henry II's star cloak

- the white Kunigunde cloak

- the Rationale

A secular embroidery that, like Gerberga's war banner, refers to a specific historical event is the famous Bayeux Tapestry. Nine linen panels, each approximately 50 cm high, are sewn together to form a tapestry over 70 m long depicting the conquest of England by William the Conqueror in 1066. In numerous individual scenes, accompanied by embroidered texts, the development is depicted from the decision of the English King Edward the Confessor to appoint the Norman Duke William, whose strict organization of his duchy he admired, as his successor in 1064, to his victory over his rival Harold Godwinson at the Battle of Hastings in 1066. The continuous depiction is framed at the top and bottom by borders showing animals, plants, fable scenes and mythical creatures, as well as scenes commenting on the plot, such as agricultural activities or details of a battle – wounded, dead, looting, etc.[8] . The layout of the embroidery follows the tradition of depicting secular events in Viking art, as fragments found in a Viking ship burial in Oseberg from the 8th or 9th century show[9] .

Contrary to earlier assumptions that William the Conqueror's wife, Matilda, had the tapestry made, research now believes that it was commissioned by Odo, Bishop of Bayeux, who was William the Conqueror's half-brother. He was bishop of Bayeux from 1049 to 1097; after the conquest of England, he was also Earl of Kent until 1088. " Diese Sichtweise wird gestützt durch die Tatsache, dass Odo in vier Szenen der Stickerei und dreimal in den Inschriften erwähnt wird […] und drei der neben den Hauptakteuren in den Inschriften benannten Personen, Wadard, Vital und Turold, die in keiner anderen zeitgenössischen Quelle der Schlacht bei Hastings genannt werden, […] sich auf Odo [beziehen]"[10]. If we follow this attribution of the patron, we can date the completion to 1077 at the latest, as it can be assumed that the tapestry was presented for the inauguration of Bayeux Cathedral.

Assumptions about where the embroidery was made vary depending on the nationality of the researchers. While French researchers assumed it was of French origin, English researchers assumed it was made in England. Nowadays, English provenance is generally accepted, with three main reasons being cited: "Zu dieser Zeit [gemeint: als Odo Graf von Kent war] gab es eine angesehene Schule für Stickerei in Canterbury […] und Stil und Technik des Teppichs deuten auf diese Schule hin. Außerdem sind Details in einer Reihe von Motiven deutlich von Illustrationen in angelsächsischen Handschriften aus dem 10. und 11. Jahrhundert"[11] and the orthographic forms of proper names in the Latin texts are strongly influenced by English[12] .

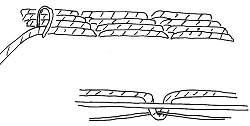

The embroidery was done with wool yarn in ten colors using the overcast stitch; contours and letters are embroidered in the stem stitch. Due to the detailed depiction of slaughter events, it is assumed that the motifs of the entire tapestry were drawn – not sketched – by a single man[13] . The execution was probably carried out by women, with several women working on the embroidery at the same time, which explains why the motifs appear somewhat "squashed" in some places, as the space had already been limited by other embroiderers working on other scenes. Moreover, it would probably not have been possible for a single person to complete such an extensive embroidery within just under eleven years, assuming that the date of completion is 1077.

Fig.2: The so-called Bayeux Stitch

Fig. 3: Depiction of animals at the top and depiction of agricultural activities at the bottom.- In: In: http://anglo-saxon.archeurope.com/@images/Bayeux%20Tapestry/scene%2012.jpg

Fig. 4: Odo of Bayeux at the Battle of Hastings.- In: http://anglo-saxon.archeurope.com/@images/Bayeux%20Tapestry/scene%2082.jpg

Fig. 5-7: The three consecutive scenes show the preparation of the meal, the serving of the food, and the eating at the table.- In:

http://anglo-saxon.archeurope.com/@images/Bayeux%20Tapestry/scene%2056.jpg,

http://anglo-saxon.archeurope.com/@images/Bayeux%20Tapestry/scene%2057.jpg,

http://anglo-saxon.archeurope.com/@images/Bayeux%20Tapestry/scene%2058.jpg

http://anglo-saxon.archeurope.com/@images/Bayeux%20Tapestry/scene%2057.jpg,

http://anglo-saxon.archeurope.com/@images/Bayeux%20Tapestry/scene%2058.jpg

The Bayeux Tapestry already shows the exceptionally high quality of English embroidery, which became known as opus anglicanum from the 13th century onwards and was valued and sought after throughout Europe. The term opus anglicanum probably did not originate in England itself, but comes from papal and other European texts[14] . It refers to the period from around 1200 to 1350, which saw the "technical, artistic and economic development of the medieval embroidery trade in England."[15]

In contrast to the wool embroidery of the Bayeux Tapestry, opus anglicanum is embroidery with silk, gold, and silver threads. " Typisch […] sind die plastisch gestickten Gesichter und das markante, wallende Haar der Figuren sowie die feine Schattierung der Kleidung"[16] . The embroidery was done with silk using split stitch, whereby the "einzelnen Reihen […] dabei so eng nebeneinander gestickt [wurden], dass sie optisch miteinander verschmolzen.“[17] Often, the split stitches were only 2 mm in size, especially in the more detailed parts of the embroidery. Three or more shades of one color were used for shading, with the direction of embroidery being important for creating a flowing impression. Metal threads were typically used for halos, borders, and backgrounds, and sometimes for clothing, and were almost exclusively worked using the buried layering technique. On the one hand, this technique protects the thread, and on the other hand, the buried thread technique creates a "movable" thread, which makes the embroidery flow. Backgrounds were often embroidered to create a geometric pattern.[18] The liveliness of the embroidery of opus anglicanum led to it also being referred to as "needle painting."

Fig. 8: Underside couching stitch.- Abb.8: Versenkte Anlegetechnik.- https://vianostra.at/scriptorium/

handarbeiten/historisches-sticken.htm

handarbeiten/historisches-sticken.htm

Fig. 9: Shoes from the tomb of Archbishop Hubert Walter, created between 1170 and 1200.- In: Browne, Clare et al (Hrsg.): English Medieval Embroidery: Opus Anglicanum, Yale 2021, S. 127

Fig. 10: The Steeple Aston Cope (detail), 1310-40.- In: https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/the-steeple-aston-cope?srsltid=AfmBOopKZ_5eL-E31TJ7voN0YofGzsPCDcwWaXUuEs

MwZyjDgzcBg-C2

MwZyjDgzcBg-C2

Fig..11: The Toledo Cope, 1320-30.- In: https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/about-opus-anglicanum?srsltid=AfmBOoqwLPXtW8iUDT-oa7ETRA_pe99TolnDAetRFboM8NBUSzeP4Vve

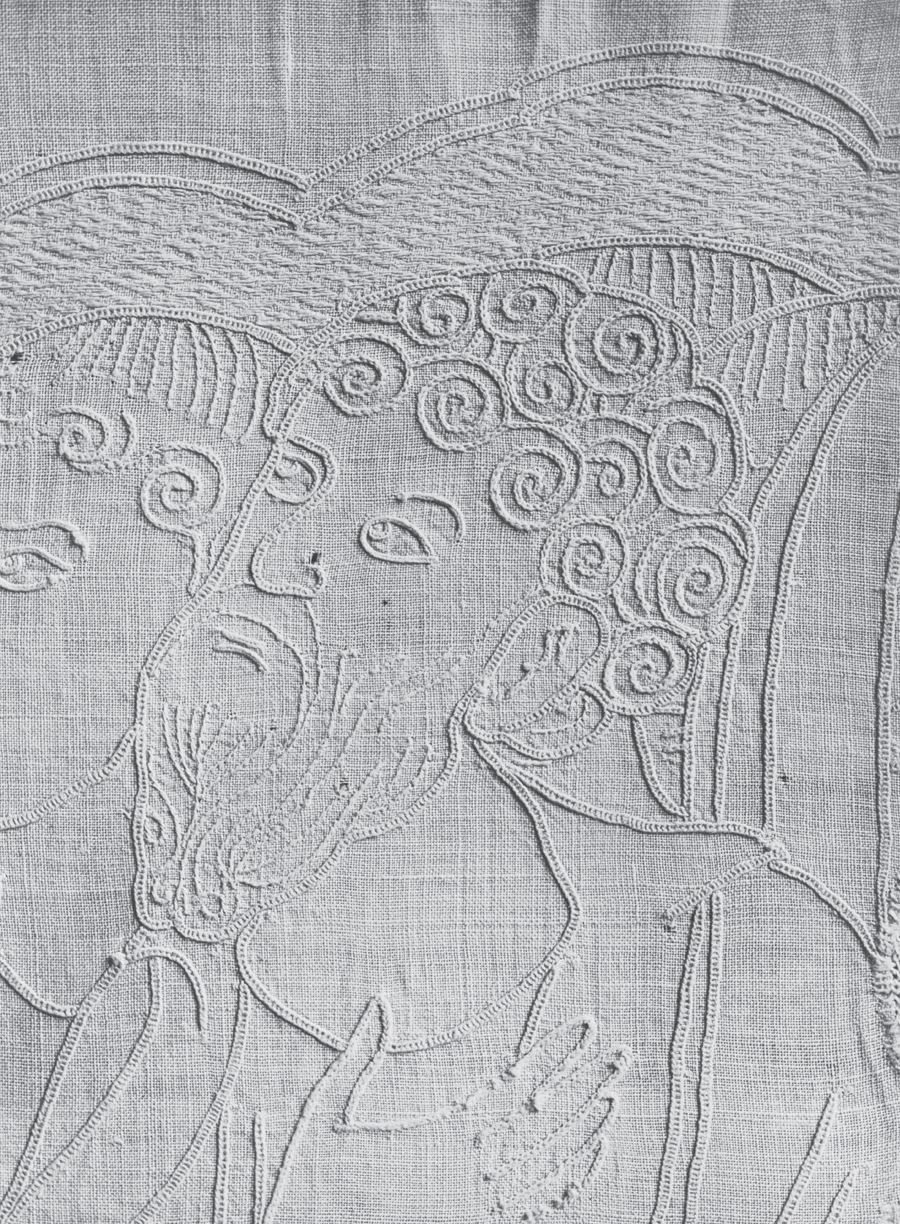

At around the same time that opus anglicanum was flourishing in England, an astonishing amount of white embroidery was to be found in German-speaking countries, especially in northern Germany. This embroidery seems to be so typical of German embroidery from the 12th century onwards[19] that it is referred to as opus teutonicum, although it is unclear when and by whom this term was first used.[20] Whitework embroidery, sometimes also called linen embroidery, is embroidery with white linen thread, more rarely with white wool, on a white embroidery ground, usually linen. In the early days of white embroidery, colored thread was used very sparingly to highlight certain special parts of the embroidery, such as halos. From the second half of the 13th century onwards, the use of colored silk embroidery threads increased. The embroidery was mainly done in chain stitch, tapestry stitch, satin stitch, and stem stitch. Occasionally, outlines were also embroidered in buttonhole stitch and filet embroidery was used for the background.[21] It is believed that whitework embroidery was very widespread in Germany because flax could be grown in the country itself and was therefore an easily accessible raw material.[22]

Early white embroidery has been preserved mainly in the form of antependia and hunger cloths.[23] From the 14th century onwards, white embroidery with secular motifs such as people, animals, and heraldic elements became more common.[24]

An altar cloth from Fulda, dating from around 1180[25], is considered to be "das älteste […] und zugleich künstlerisch vollendestete Werk."[26] It is believed to have been burned "1945 zusammen mit unzähligen anderen textilen Kunstwerken aus dem Besitz des Kunstgewerbemuseums an deren hauptsächlichem Bergungsort, im Schloss Sophienhof in Mecklenburg,"[27] , so that Falke's description and a few surviving photos must be relied upon to make statements about the embroidery. The outlines were executed in double chain stitch on a fine, regularly woven linen ground; the areas remained free except for a gloriole on the right edge, the halos, ointment vessels, rosettes, and animals in the corner medallions. The latter were embroidered in full in monastic stitch. Monastic stitch was also used for the inscription.[28]

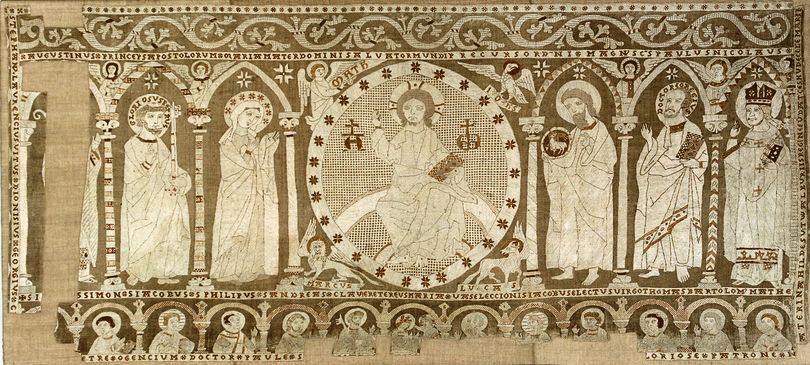

White embroidery proves particularly interesting for the purpose of this work, which is to examine the history of cross-stitch. Around 1260, an antependium was produced in the monastery of Heiningen near Wolfenbüttel, depicting Christ enthroned on the globe, surrounded by Mary, John the Baptist, and the twelve apostles. The embroidery ground consists partly of bleached and partly of unbleached linen, creating color differences. Colored silk thread was used for the cross-stitch in the ornaments and inscription, while the embroidery techniques commonly used for white embroidery were used for the remaining elements of the image.[29]

An altar cloth from Fulda, dating from around 1180[25], is considered to be "das älteste […] und zugleich künstlerisch vollendestete Werk."[26] It is believed to have been burned "1945 zusammen mit unzähligen anderen textilen Kunstwerken aus dem Besitz des Kunstgewerbemuseums an deren hauptsächlichem Bergungsort, im Schloss Sophienhof in Mecklenburg,"[27] , so that Falke's description and a few surviving photos must be relied upon to make statements about the embroidery. The outlines were executed in double chain stitch on a fine, regularly woven linen ground; the areas remained free except for a gloriole on the right edge, the halos, ointment vessels, rosettes, and animals in the corner medallions. The latter were embroidered in full in monastic stitch. Monastic stitch was also used for the inscription.[28]

White embroidery proves particularly interesting for the purpose of this work, which is to examine the history of cross-stitch. Around 1260, an antependium was produced in the monastery of Heiningen near Wolfenbüttel, depicting Christ enthroned on the globe, surrounded by Mary, John the Baptist, and the twelve apostles. The embroidery ground consists partly of bleached and partly of unbleached linen, creating color differences. Colored silk thread was used for the cross-stitch in the ornaments and inscription, while the embroidery techniques commonly used for white embroidery were used for the remaining elements of the image.[29]

Fig. 12: Fulda altar cloth, around 1180.- In: Lothar Lambacher, Inkunabeln des Opus teutonicum. Die verlorenen romanischen Weißstickereien des Berliner Kunstgewerbemuseums, S. 111

Fig. 13: Heininger antependium, around 1260.- In: https://www.reddit.com/r/Medievalart/comments/

1khk0lx/lenten_cloth_or_antependium_nuns_of_heiningen/

?tl=de

1khk0lx/lenten_cloth_or_antependium_nuns_of_heiningen/

?tl=de

Fig. 14: Two apostles, Heininger antependium (detail), around 1260.- In: August Fink; Das weisse Antependium aus Kloster Heiningen (Jehrbuch der Berliner Museen 1959), S. 173

There is disagreement among researchers about the dating of a – albeit colored – antependium that belongs (or belonged) to Halberstadt Cathedral. The antependium, embroidered on half-silk satin, is interesting here because it was lined and an inscription was embroidered on the upper edge of the lining with green silk. Cross-stitch was used for this inscription. The lining is dated to around 1300 or the first half of the 14th century, while the embroidery probably dates from the second half of the 13th century.[30]

Four altar cloths in white embroidery have been preserved from the Premonstratensian convent of Altenberg an der Lahn, two of which date from the 13th century and two from the 14th century.[31] Images of the pieces, including a detailed description of the embroidery techniques used, are difficult to find. However, it appears that the altar cloth from around 1350 in the Cleveland Museum was partially embroidered in cross-stitch, namely the zigzag border around the edge and the arched frames around the figurative and animal elements.

Four altar cloths in white embroidery have been preserved from the Premonstratensian convent of Altenberg an der Lahn, two of which date from the 13th century and two from the 14th century.[31] Images of the pieces, including a detailed description of the embroidery techniques used, are difficult to find. However, it appears that the altar cloth from around 1350 in the Cleveland Museum was partially embroidered in cross-stitch, namely the zigzag border around the edge and the arched frames around the figurative and animal elements.

Fig. 15: Altar cloth from the Altenberg/Lahn monastery, around 1330. The figures include the Three Kings, St. Elizabeth and her daughter, who was the abbess of Altenberg, and St. Nicholas. A Latin inscription names the embroiderers as Sophia, Hardewigis, and Lucardis.- In: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/466843

A hunger cloth dating from the early 14th century comes from the Lüne monastery. The cloth shows damage in several places, which can be explained by the tension caused by its use. Some of the damage has been repaired, although it is noticeable that holes above the right foot or leg and under the left arm of the fourth figure from the right in the lower part of the cloth have been repaired by cross-stitching.[32] Unfortunately, the question of why no attempt was made to repair the holes using embroidery techniques faithful to the original remains unanswered.

Fig. 16: Lenten veil from the Lüne monastery, first half of the 14th century.(own photo)

In addition to antependia, altar cloths, and fasting or hunger cloths, lectern cloths were also a common sight in medieval monasteries and churches, as they all served to present biblical content, legends of saints, etc. in a memorable way through pictorial representations. In the late 14th century, a lectern cloth was made for the Wiesenkirche (St. Maria zur Wiese) in Soest[33], which bears a striking resemblance to white embroidery. "Auf einen grauen Leinengrund sind mit weißem Leinengarn in unterschiedlichen Sticharten flächendeckend Ornamente und figürliche Darstellungen aufgestickt worden."[34] The embroidery techniques used include cross-stitch, which was used for the border edgings, inner edgings, and some ornaments.

Fig. 17: Lectern cover from Maria zur Wiese, Soest, second half of the 14th century.-

In: Marti, Susan: Geflecht aus Text und Bild – Vorläufige Überlegungen zu

einer Leinenstickerei aus der Soester Wiesenkirche, S. 60

In: Marti, Susan: Geflecht aus Text und Bild – Vorläufige Überlegungen zu

einer Leinenstickerei aus der Soester Wiesenkirche, S. 60

Although cross-stitch is not the predominant stitch used in whitework embroidery, it is clear that it was known and used. This raises the question of whether cross-stitch embroidery existed before the 12th century. It is also interesting to know when and how cross-stitch became the embroidery technique that is currently considered the embroidery technique par excellence. To answer these questions, it is necessary to examine whether the existing textile remains with embroidery are representative or not. It may be helpful to consider who produced or commissioned the embroidery and who carried out the embroidery work. These questions will be explored in the next "chapter" in an excursus.