Embroidery at the turn of the century

In the second half of the 19th century, Berlin wool work was already viewed critically, albeit not by all sections of the population. This criticism, which originated in England, was directed against the decorative arts as a whole and began as early as 1835, when an investigative report by the Parliamentary Select Committee on Art and Manufactures found that the quality of English products could not compete with that of other exporting countries. In addition to the lack of quality, the commission criticized "the rampant and indiscriminate use of ornamentation. As an example of poor design, critics lambasted the 'deceptive' three-dimensional, illusionistic patterns that decorated the two-dimensional surfaces of carpets and wallpapers."[1]

This criticism intensified in 1851 when the first World's Fair was held in London. Critics lamented mass production, which led to poor quality, "rushed in construction, overly focused on ornamentation without purpose, and unmindful of the materials used"[2] The degrading social conditions of the production process[3] were also cited negatively as both a cause and a consequence of industrial production. As a consequence, Henry Cole (1808–1882), Richard Redgrave (1804–1888), and Owen Jones (1809–1874) were appointed to a working group in England, which, with the support of Prince Albert, was tasked with developing guidelines for a modern and morally appropriate design language.[4] This can be seen as the origin of the counter-movement to industrialization that later became known as the Arts and Crafts Movement, which found resonance in other industrialized countries and spread there with various adaptations.

The aforementioned shortcomings of the decorative arts also affected embroidery, especially "Berlin wool work," which was based on the mass production of colored embroidery patterns. In her essay, Talia Schaffer lists the attitudes toward embroidery that led to the success of "Berlin wool work" and were based on a zeitgeist characterized by "the machine-inflected, cheap, easily made, imitative, mass-produced, and modern"[5] . She agrees with Stepanova's portrayal that "Berlin wool work" resulted in a loss of creativity and diversity in embroidery techniques[6] when she argues that the individuality of the embroiderers was reduced to the level of a machine loom, but that "this chance to prove one could work like a steam power-loom was precisely the appeal of Berlin woolwork"[7] because it allowed the embroiderers to prove that they also possessed the skills that made English industry successful.[8] Another criticism is that the garments and accessories that were embroidered meant that embroidery was closely linked to ever-changing fashions, resulting in the production of disposable products rather than timeless art.[9] In summary, Schaffer notes that the women's embroidery produced products that represented "among other things, a love of productivity itself, a sign of allegiance to a nation exulting in its industrial might."[10]

In addition to the aforementioned fundamental criticisms, which primarily address de-individualization, there are two further aspects that have also shaped the "reputation" of embroidery to the present day. On the one hand, embroidery is criticized as a waste of time.[11] Furthermore, a more aesthetic point of view is taken, in that Victorian decorative art in general and "Berlin Wool Work" in particular are considered to be a "Förderung des schlechten Geschmacks"[12] because the embroideries were chosen "für die unpassendsten Anlässe"[13] . The multitude of embroideries that copied original paintings by old masters can also be considered tasteless. Apart from the fact that the original paintings were intended and executed as paintings, these embroideries did not convey any kind of message; they remained inappropriate imitations, which is why they can also be considered kitsch.

In response to the findings of the parliamentary commission in 1835, the Government School of Design was founded in 1837 and renamed the National Art Training School in 1853.[14] This clearly shows how seriously the state took criticism of industrially manufactured goods and considered it essential for economic success. The working group mentioned above, established in England in 1851, addressed questions of ornamentation[15] and developed three principles that were to be decisive for a modern design language: "first, that decoration is secondary to form; second, that form is dictated by function and the materials used; and third, that design should derive from historical English and non-Western ornament as well as plant and animal sources, distilled into simple, linear motifs"[16] These principles were almost like guidelines: they were posted on posters in the rooms of the Schools of Design with explanations so that they were always present to the artists.[17]

Shortly after these attempts at reform, and also on the occasion of the 1851 World's Fair, a group of critics of Victorian art emerged who became known as the Arts and Crafts Movement, a counter-movement to industrialization in the field of decorative arts. They agreed with the above-mentioned points of criticism, but differed significantly in terms of the solution. While the state-supported efforts were primarily concerned with modernizing and improving the quality of the design of industrially manufactured goods, the group around William Morris (1834-1896) and John Ruskin (1819-1900) also included criticism of the social consequences of industrialization. They took the alienation of workers from their work caused by industrial labor and the accompanying self-alienation as an opportunity to set different priorities for the production of goods.[18] From their point of view, "a return to a system of manufacture based on small-scale workshops"[19] was a possibility "that allowed their makers to remain connected both with their product and with other people"[20] . This backward-looking attitude was modeled on the medieval world with its connection to nature.[21] Morris believed that "a happy worker made beautiful things regardless of ability, and that good, moral design could only come from a good and moral society"[22] .

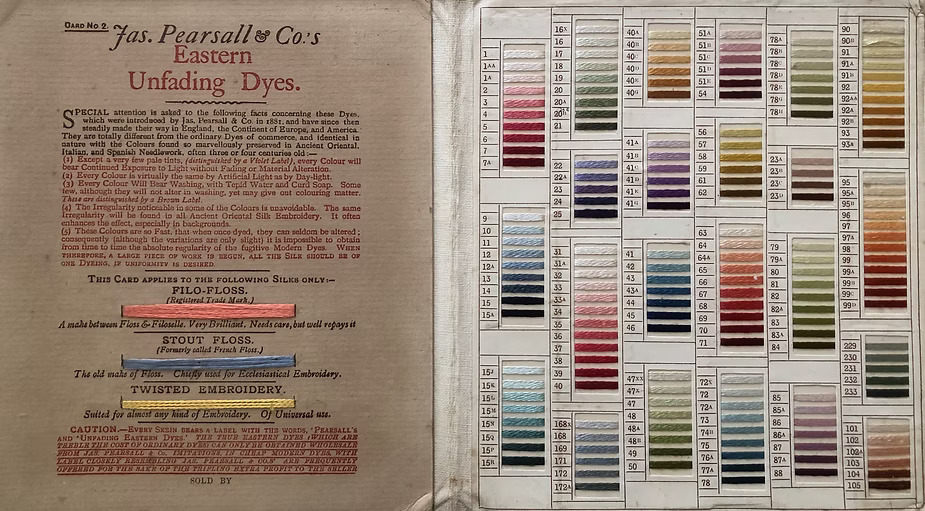

The goals of the Arts and Crafts Movement were also applied to embroidery. This gave rise to what was known as Art Needlework, which differed from the counted embroidery of "Berlin Wool Work" in that it was embroidered according to freely drawn patterns[23] and thus inevitably drew on the old techniques of tracing. Accordingly, as in medieval embroidery, the outlines were embroidered and then filled in. A variety of stitches were used[24], and emphasis was placed on careful shading and the use of naturally dyed silk[25] , which was "totally different from the ordinary dyes of commerce and identical in nature to the colors found so marvelously preserved in ancient Oriental, Italian, and Spanish needlework, often four or three centuries old"[26] . Preferred motifs tended to be stylized flowers and other motifs from nature, as well as geometric patterns and shapes. The paintings in medieval manuscripts and drawings in Renaissance flower and animal books also served as models.{27] The colors used in embroidery were often the muted colors found in nature, "featuring shades of green, brown, blue, and rust. These colors were often complemented by brighter accents, such as red or gold."[28] Efforts to transform embroidery from a domestic activity carried out by amateurs into a serious art form[29] were supported by the founding of the Ladies Work Society in 1875, which was not only intended to fulfill the aforementioned purpose, but also – in line with Morris' socialist ideals – to contribute to women being paid fairly for their embroidery so that they could live with dignity. [30] The Royal School of Needlework[31] , founded in 1872, and the Embroidery Societies, founded in the 1890s, contributed to the spread of Arts and Crafts Movement embroidery.[32]

The goals of the Arts and Crafts Movement were also applied to embroidery. This gave rise to what was known as Art Needlework, which differed from the counted embroidery of "Berlin Wool Work" in that it was embroidered according to freely drawn patterns[23] and thus inevitably drew on the old techniques of tracing. Accordingly, as in medieval embroidery, the outlines were embroidered and then filled in. A variety of stitches were used[24], and emphasis was placed on careful shading and the use of naturally dyed silk[25] , which was "totally different from the ordinary dyes of commerce and identical in nature to the colors found so marvelously preserved in ancient Oriental, Italian, and Spanish needlework, often four or three centuries old"[26] . Preferred motifs tended to be stylized flowers and other motifs from nature, as well as geometric patterns and shapes. The paintings in medieval manuscripts and drawings in Renaissance flower and animal books also served as models.{27] The colors used in embroidery were often the muted colors found in nature, "featuring shades of green, brown, blue, and rust. These colors were often complemented by brighter accents, such as red or gold."[28] Efforts to transform embroidery from a domestic activity carried out by amateurs into a serious art form[29] were supported by the founding of the Ladies Work Society in 1875, which was not only intended to fulfill the aforementioned purpose, but also – in line with Morris' socialist ideals – to contribute to women being paid fairly for their embroidery so that they could live with dignity. [30] The Royal School of Needlework[31] , founded in 1872, and the Embroidery Societies, founded in the 1890s, contributed to the spread of Arts and Crafts Movement embroidery.[32]

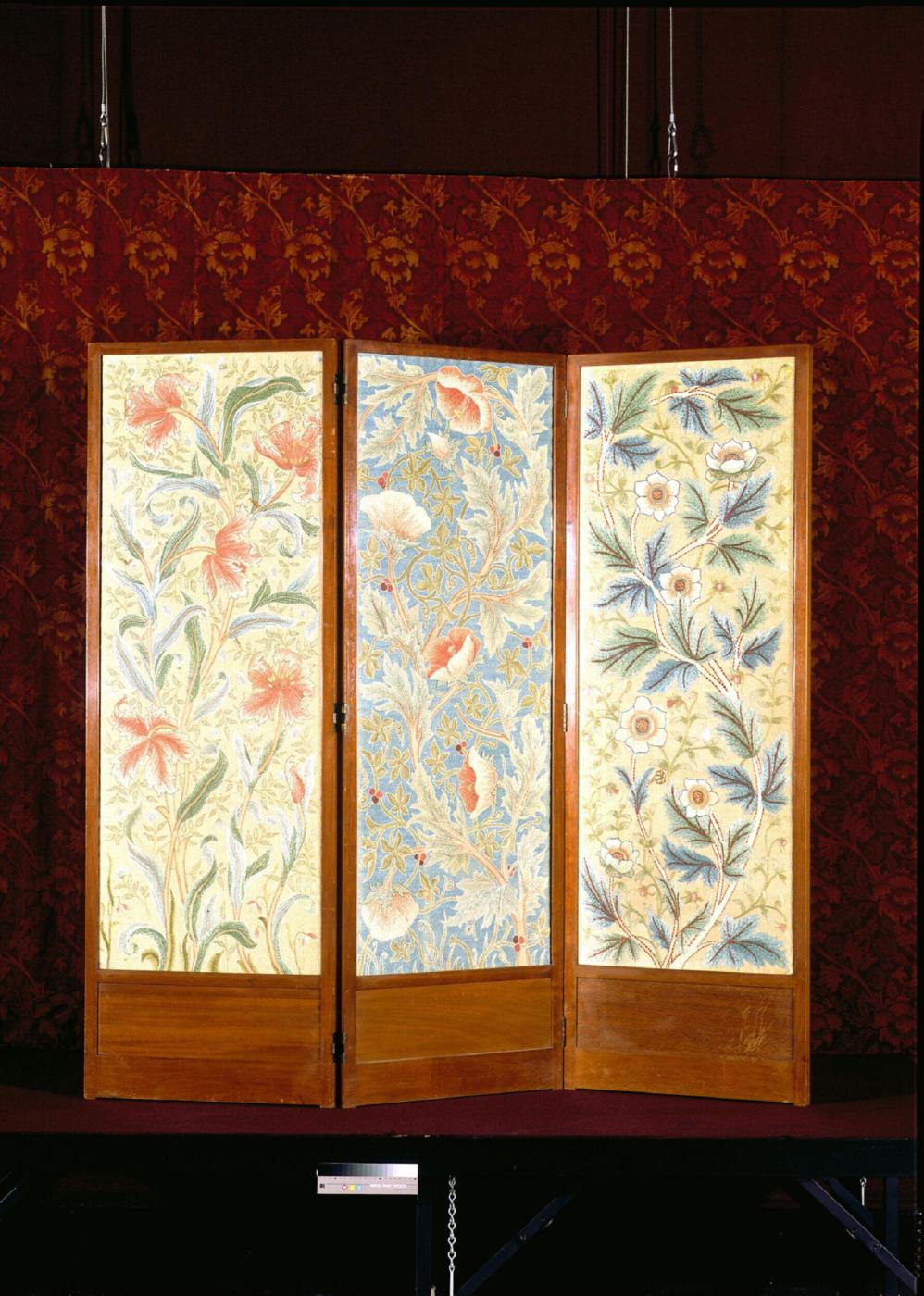

Fig. 1: Three-part screen with mahogany frame and silk embroidery in satin stitch, darning stitch, and style stitch, created between 1885 and 1910. The pattern was designed by John Henry Dearle, and the screen, including the embroidery, was manufactured in the workshops of William Morris. - https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O78101/screen-john-henry-dearle/

Fig. 2: Embroidered bedspread or hanging, late 19th century, possibly designed and executed by May Morris. - https://www.metmuseum.org/art/

collection/search/744452

collection/search/744452

Fig. 3: Altar cloth, embroidered by May Morris, 1912. The silk embroidery is fully embroidered with relatively bright colors and gold thread. For the crosses, an appliqué technique was used with gold threads on a silver-colored silk background.- https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/arts-and-crafts-an-introduction?srsltid=AfmBOopXn0-fTKQs2XI9pjeQL_

TB9lY9E5xvYW96aVrQtyCP6v1O_yrh

TB9lY9E5xvYW96aVrQtyCP6v1O_yrh

Fig. 4: Color chart from Pearsall & Co., Eastern Unfading Dyes thread card, late 19th century. In: Halse, Lynn: Art Embroidery part II, 2020 - https://www.ornamentalembroidery.com/

post/art-embroidery-part-ii

post/art-embroidery-part-ii

The Arts and Crafts Movement experienced a significant decline, particularly in the 1920s, as it was too labor-intensive and costly and could therefore only serve an elite clientele. Due to its backward-looking nature, the Arts and Crafts Movement failed to keep up with contemporary developments.[33]

Regardless of the contradiction between the goals of the Arts and Crafts Movement and the zeitgeist striving for economic success, the ideas of the Arts and Crafts Movement spread throughout Europe. In Germany, a similar movement emerged in the form of Jugendstil or Art Nouveau. Art Nouveau sought to break down the barriers between art and design. The aim was to create art for everyone, which meant seeing beauty in everything[34] and integrating this beauty into people's everyday lives.[35] In this respect, Art Nouveau was significantly less elitist in its goals than the Arts and Crafts Movement. Although Art Nouveau was also a counter-movement to industrialization in that it sought to bring man and nature into harmony, it did not reject technological developments and industrial production as completely as the Arts and Crafts Movement.

Art Nouveau did not take works from past eras as models for contemporary artistic creation, as they had emerged from and reflected the spirit of their respective times, according to one of the movement's leading theorists.[36] In the present, "Zweck, Material und Fügung [sind] die einzigen Direktiven."[37] This means that at the beginning of a creative process, "sich den Zweck eines jeden Gegenstandes zunächst einmal recht deutlich klarzumachen und die Form logisch aus dem Zweck zu entwickeln. […] Zu der Gestaltung nach dem Zweck [komme] also die Gestaltung nach dem Charakter des Materials, und mit der Rücksicht auf das Material [sei] gleichzeitig die Rücksicht auf die dem Material entsprechende Konstruktion gegeben."[38] By observing these principles, inner truthfulness and genuine solidity are achieved. This distinguishes contemporary arts and crafts production from the pomp that the bourgeoisie displayed in the service of its social ambitions.[39] In this way, the arts and crafts movement contributes to " die heutigen Gesellschaftsklassen zur Gediegenheit, Wahrhaftigkeit und bürgerlichen Einfachheit zurückzuerziehen."[40] The aforementioned principles distinguish Art Nouveau from the Arts and Crafts Movement: the goals of usability, material appropriateness, and functionality of a work are opposed to the claim that works of art should be complete in themselves, characterized by timelessness and a message that transcends themselves. They are also far removed from the belief that art needs neither a message nor a purpose (L'art pour l'art).

Embroidery was particularly well suited to integrating beauty into people's everyday lives. In line with the goal of uniting humans and nature, organic shapes and curved lines were preferred. They were used as a "metaphor for the freedom and release [...] from the weight of artistic tradition and critical expectations"[41]. In addition, there were floral ornamental abstractions as well as geometric shapes that made it difficult to recognize that they were taken from nature[42] , depictions of animals, and mythological figures.[43] Another characteristic feature of the embroidery was the "whip lash" form, an asymmetrical line, often curved in an S-shape. The name comes from an embroidery design by Hermann Obrist in 1895.[44] Like the Arts and Crafts Movement, Art Nouveau was also more of an elitist movement, even if that did not correspond to its goals. One can only assume that the zeitgeist, which was characterized by increasing nationalism on the eve of World War I, did not meet with much interest in a movement that was characterized by critical attitudes.

Cross-stitch was not a popular embroidery technique for either the Arts and Crafts Movement or Art Nouveau. The reason may be that other embroidery techniques such as satin stitch or monastic stitch seemed better suited to creating curved, flowing shapes. Another reason may be that people wanted to consciously distance themselves from the widespread style of Berlin wool work and therefore rejected the so-called counted stitches.

Regardless of the contradiction between the goals of the Arts and Crafts Movement and the zeitgeist striving for economic success, the ideas of the Arts and Crafts Movement spread throughout Europe. In Germany, a similar movement emerged in the form of Jugendstil or Art Nouveau. Art Nouveau sought to break down the barriers between art and design. The aim was to create art for everyone, which meant seeing beauty in everything[34] and integrating this beauty into people's everyday lives.[35] In this respect, Art Nouveau was significantly less elitist in its goals than the Arts and Crafts Movement. Although Art Nouveau was also a counter-movement to industrialization in that it sought to bring man and nature into harmony, it did not reject technological developments and industrial production as completely as the Arts and Crafts Movement.

Art Nouveau did not take works from past eras as models for contemporary artistic creation, as they had emerged from and reflected the spirit of their respective times, according to one of the movement's leading theorists.[36] In the present, "Zweck, Material und Fügung [sind] die einzigen Direktiven."[37] This means that at the beginning of a creative process, "sich den Zweck eines jeden Gegenstandes zunächst einmal recht deutlich klarzumachen und die Form logisch aus dem Zweck zu entwickeln. […] Zu der Gestaltung nach dem Zweck [komme] also die Gestaltung nach dem Charakter des Materials, und mit der Rücksicht auf das Material [sei] gleichzeitig die Rücksicht auf die dem Material entsprechende Konstruktion gegeben."[38] By observing these principles, inner truthfulness and genuine solidity are achieved. This distinguishes contemporary arts and crafts production from the pomp that the bourgeoisie displayed in the service of its social ambitions.[39] In this way, the arts and crafts movement contributes to " die heutigen Gesellschaftsklassen zur Gediegenheit, Wahrhaftigkeit und bürgerlichen Einfachheit zurückzuerziehen."[40] The aforementioned principles distinguish Art Nouveau from the Arts and Crafts Movement: the goals of usability, material appropriateness, and functionality of a work are opposed to the claim that works of art should be complete in themselves, characterized by timelessness and a message that transcends themselves. They are also far removed from the belief that art needs neither a message nor a purpose (L'art pour l'art).

Embroidery was particularly well suited to integrating beauty into people's everyday lives. In line with the goal of uniting humans and nature, organic shapes and curved lines were preferred. They were used as a "metaphor for the freedom and release [...] from the weight of artistic tradition and critical expectations"[41]. In addition, there were floral ornamental abstractions as well as geometric shapes that made it difficult to recognize that they were taken from nature[42] , depictions of animals, and mythological figures.[43] Another characteristic feature of the embroidery was the "whip lash" form, an asymmetrical line, often curved in an S-shape. The name comes from an embroidery design by Hermann Obrist in 1895.[44] Like the Arts and Crafts Movement, Art Nouveau was also more of an elitist movement, even if that did not correspond to its goals. One can only assume that the zeitgeist, which was characterized by increasing nationalism on the eve of World War I, did not meet with much interest in a movement that was characterized by critical attitudes.

Cross-stitch was not a popular embroidery technique for either the Arts and Crafts Movement or Art Nouveau. The reason may be that other embroidery techniques such as satin stitch or monastic stitch seemed better suited to creating curved, flowing shapes. Another reason may be that people wanted to consciously distance themselves from the widespread style of Berlin wool work and therefore rejected the so-called counted stitches.

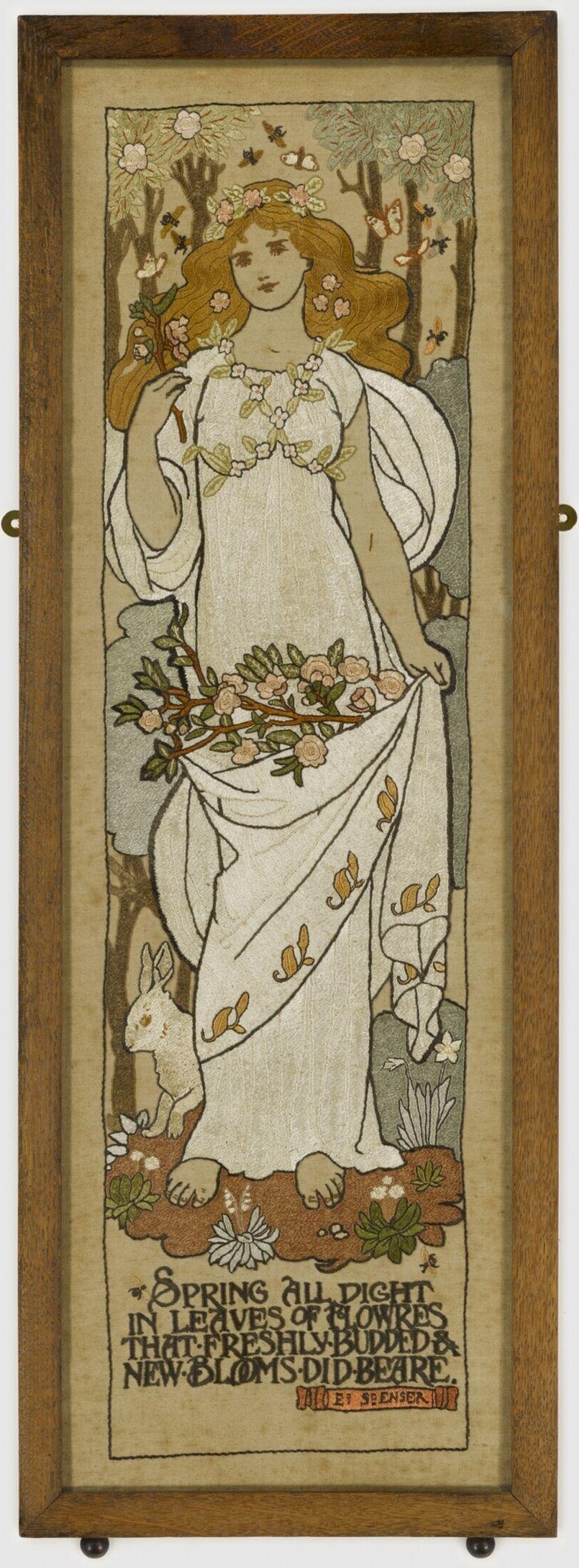

Fig. 5: Part of a four-part screen depicting the four seasons, here spring. The text is taken from the poem "The Faerie Queene" by Edmund Spenser, written in 1590/1596. The text reads "'SPRING ALL DIGHT / IN LEAVES OF FLOWES / THAT FRESHLY BUDDED & / NEW BLOOMS DID BEARE. / E. SPENSER." The design shows the close connection between visual art and literature and thus represents the pursuit of a Gesamtkunstwerk, or total work of art. - https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O1459621/screen-panel-set/

Fig. 6: Hermann Obrist, wall hanging with cyclamen, wool fabric with silk embroidery, around 1895.- https://www.kunsthalle-muc.de/jugendstil/