German samplers

This section will examine the detailed differences in the development of samplers and thus also in the use of cross-stitch in samplers between England and Germany. However, the general line of development is so similar that one can speak of a common culture of sampler embroidery.

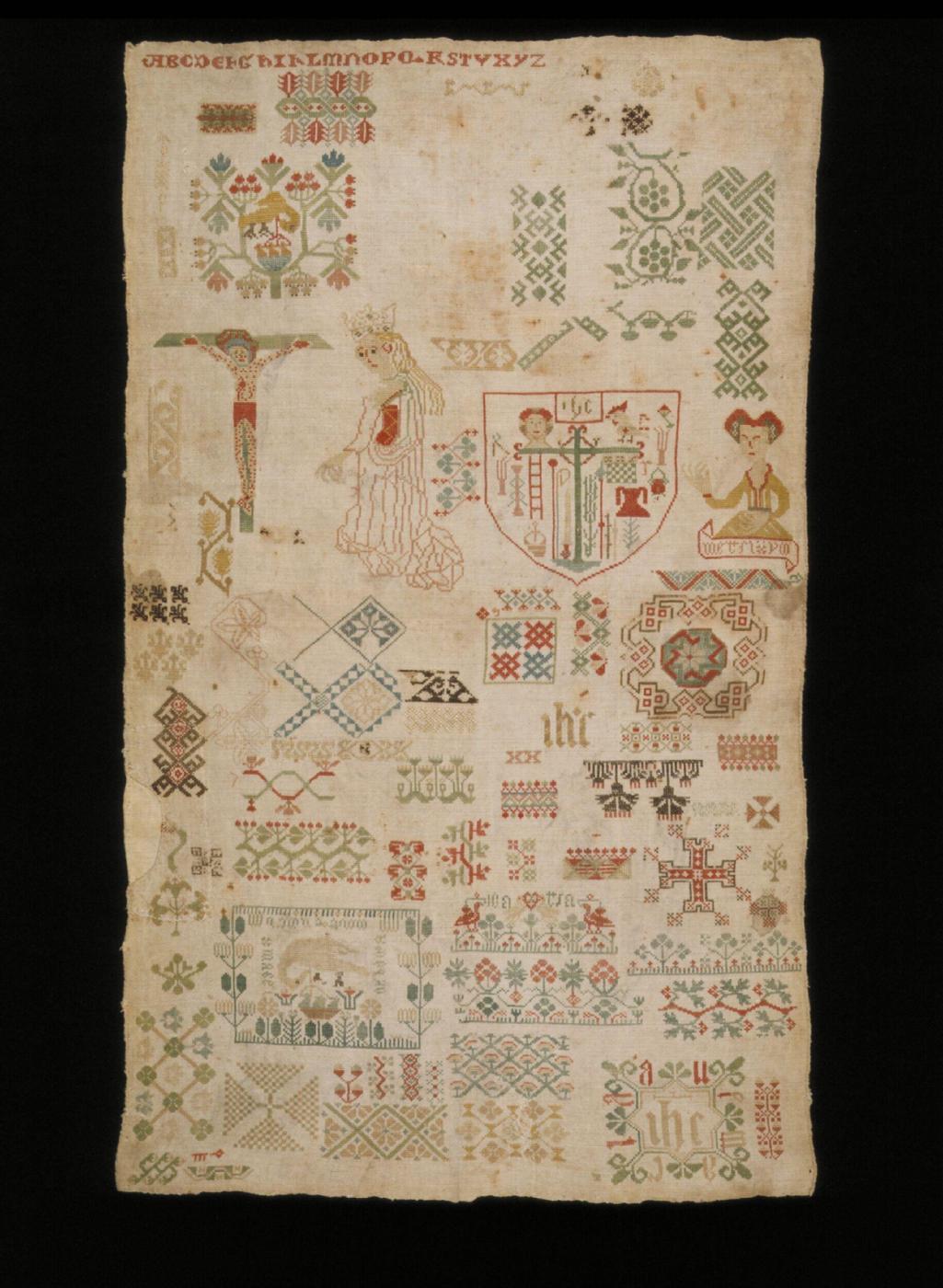

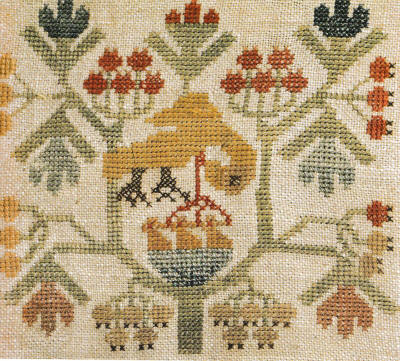

As mentioned in the chapter on samplers, the earliest surviving German samplers feature cross-stitch embroidery dating from the first half of the 16th century.[1] This sampler can clearly be classified as a spot sampler: it features various geometric patterns, embroidered in cross-stitch and long-arm cross-stitch, arranged randomly, usually with only one repeat each. An alphabet is located at the very top of the cloth, and in the middle, the embroiderer has obviously practiced the abbreviation "ihs" for Iesus Hominum Salvator, which she then uses at the bottom right as the center of a small pattern whose border is decorated with letters. Next to it, the picture shows various elements with a Christian reference: Christ on the cross, a kneeling queen, presumably the Virgin Mary, a cross with the instruments of torture, which tell the story of Christ's suffering in brief, beginning with Peter's betrayal, and two depictions of a pelican opening its own breast with its beak, letting its blood drip onto its dead young and thus bringing them back to life – a symbol of Christ's sacrificial death. There are also depictions of two geese and a woman who has raised her right hand as if she were holding something thin, perhaps a thread, between her thumb and index finger. Both images have inscriptions, which I was unable to decipher. The depiction of the crucifixion, the Mother of God, and the instruments of torture can certainly be explained by the fact that at the time of its creation, the Christian faith was undoubtedly part of everyone's intellectual concept; the depiction of the pelican can also be explained by Christian iconography[2] . The fact that the depictions of the pelican, the geese, and the unidentifiable woman are accompanied by "captions" can be attributed to the Renaissance period, when people attempted to record knowledge with the aid of embroidery and label it with a description[3].

Fig. 1: Embroidery sampler, Germany, first half of the 16th century.- https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O69791/sampler-unknown/

Fig. 2: Detail from the above sampler,

Germany, first half of the 16th century: Pelican with its young

Germany, first half of the 16th century: Pelican with its young

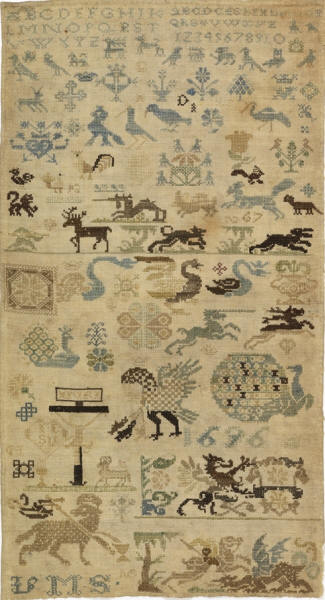

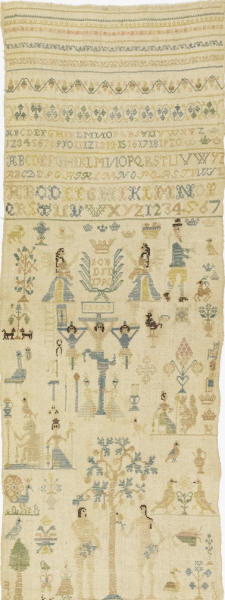

In terms of motifs and their execution, this sampler seems to mark the beginning of a tradition. The motifs of the crucifixion, instruments of torture, the Lamb of God, Adam and Eve under the apple tree, and similar religious motifs can be found on almost all German embroidery samplers until the 19th century, along with depictions of animals that have symbolic meaning in the ecclesiastical narrative tradition. They occur mainly in the Protestant north of Germany, while in the Catholic south, crucifixion is often the central motif, along with saints and the Virgin Mary.[4] The consistent and extremely frequent use of Christian motifs seems to make inscriptions with religious and moral content superfluous in German samplers, especially since the meanings of the motifs were generally known and understood at the time.[5] . It is therefore striking that in 1752, the words "Gloria in excelsis deo"[6] were embroidered on a sampler, and in 1755, the words "Soli deo gloria"[7] were embroidered on another sampler. Inscriptions such as "Alles mit Gott" (Everything with God) did not reappear until the end of the 19th/beginning of the 20th century. The distinctive Christian iconography on German samplers makes them very different from the inscription-dominated English samplers.

In addition to Christian motifs, German samplers feature the same elements as English samplers: " Blumen und Früchte allein und in Vasen und Körben, Zweige, Ranken und Bäume, Wappen und Wappentiere, Wildtiere wie Hirsche, Rehe, Hasen, Eichhörnchen, Störche und Krebse, und Haustiere wie Hunde, Katzen, Tauben, Pfauen, Papageien, Schafe, Ziegen und Gänse zusammen mit Hirte und Hirtin, Hähne […] Personifikationen für die Gerechtigkeit (justitia), die Hoffnung (Spes), den Frieden (Pax), die Milde (Clementia), das Glück (Fortuna) sowie das pflanzliche Wachstum (Ceres) […] Zu Beginn des 19. Jahrhunderts wurden dazu die biedermeierlichen Zeichen der Freundschaft eingefügt, etwa Urnen, Altäre und Grabmonumente in parkähnlichen Gärten.[8]

In addition to Christian motifs, German samplers feature the same elements as English samplers: " Blumen und Früchte allein und in Vasen und Körben, Zweige, Ranken und Bäume, Wappen und Wappentiere, Wildtiere wie Hirsche, Rehe, Hasen, Eichhörnchen, Störche und Krebse, und Haustiere wie Hunde, Katzen, Tauben, Pfauen, Papageien, Schafe, Ziegen und Gänse zusammen mit Hirte und Hirtin, Hähne […] Personifikationen für die Gerechtigkeit (justitia), die Hoffnung (Spes), den Frieden (Pax), die Milde (Clementia), das Glück (Fortuna) sowie das pflanzliche Wachstum (Ceres) […] Zu Beginn des 19. Jahrhunderts wurden dazu die biedermeierlichen Zeichen der Freundschaft eingefügt, etwa Urnen, Altäre und Grabmonumente in parkähnlichen Gärten.[8]

Fig. 3: Embroidery sampler, 1697. This sampler shows a mixture of Christian motifs and animal motifs. The Lamb of God is depicted at the bottom left, above it the crucifixion scene, and at the bottom right is the battle of St. George and the dragon. Some of the animals depicted have symbolic meaning: the eagle stands for renewal and baptism, the peacock for immortality and resurrection, the unicorn for Christ, the swan for purity, and much more. The sampler is worked in cross stitch and double running stitch.-

https://collection.cooperhewitt.org/

objects/18564241/

https://collection.cooperhewitt.org/

objects/18564241/

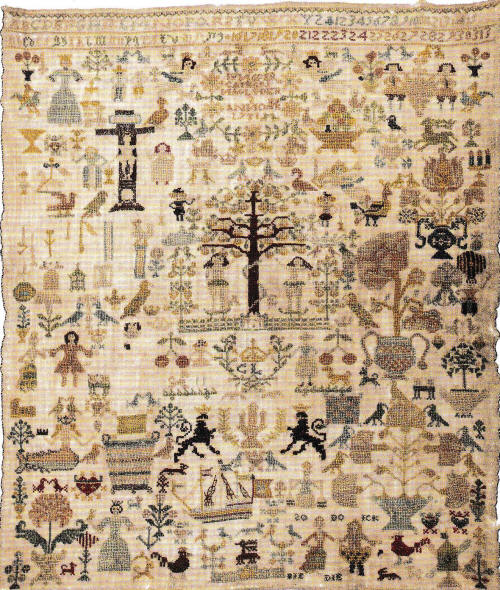

Fig. 4: Embroidery sampler, 1790. The cloth features religious and everyday motifs. Among the border motifs, alphabets, and numerals worked in rows, the central part of this sampler depicts the crucifixion as redemption from original sin, represented by Adam and Eve under the apple tree. This arrangement suggests that the cloth was embroidered in southern Germany. Here, too, there are animal motifs that have symbolic character: the peacock, the swan, the pair of doves as a symbol of love and fidelity, the spinning monkey as a symbol of vanity and malice, the dog as a symbol of loyalty, and many more. There is also a stork with a baby in its beak, which suggests that the cloth may have been made for the engagement or wedding of ICB and DFD, whose initials are marked on it. The cloth is worked in cross-stitch and stem stitch.-

https://collection.cooperhewitt.org/

objects/18616691/

https://collection.cooperhewitt.org/

objects/18616691/

Fig. 5: Embroidery sampler in picture format, 1680. In addition to border patterns, alphabets, and numerals, the cloth features many floral patterns, but reserves a row on the right-hand side

a row for Christian symbols. On the left is the crucifixion scene with the arma Christi, and on the right is the representation of Heavenly Jerusalem as the end point of salvation history. The cloth is embroidered in cross stitch, eyelet stitch, and Holbein stitch.-

https://www.schlossmuseum.de/sammlungen/

kaleidoskop/kaleidoskop-61-70/65-ein-stickmustertuch-von-1680/

a row for Christian symbols. On the left is the crucifixion scene with the arma Christi, and on the right is the representation of Heavenly Jerusalem as the end point of salvation history. The cloth is embroidered in cross stitch, eyelet stitch, and Holbein stitch.-

https://www.schlossmuseum.de/sammlungen/

kaleidoskop/kaleidoskop-61-70/65-ein-stickmustertuch-von-1680/

Fig. 6: Embroidery sampler by Catharina Lüders, 1731. Countless motifs adorn this cloth, which is exceptionally marked with a name. Religious motifs include the crucifixion scene with Mary and John, the arma Christi, Adam and Eve under the apple tree, and the biblical explorers Joshua and Caleb with the grape. As allegories of the virtues of justice and hope, there is a female figure with scales and a sword and a female figure with an anchor and a bird. A windmill, a water carrier, and a ship suggest that the sampler originated in northern Germany. At the bottom edge, there is a couple holding hands with the inscription "SO DO ICK BIE DIE," which presumably expresses the embroiderer's desire to be with the man she loves. This is also suggested by numerous symbols of love and fidelity. As far as can be seen, the cloth is embroidered in cross-stitch.-

In: Andrea Madadi, Ausgezählt. Stickmustertücher in den Vierlanden. Bergedorfer Museumslandschaft (ed.), Hamburg 2021, p. 62

In: Andrea Madadi, Ausgezählt. Stickmustertücher in den Vierlanden. Bergedorfer Museumslandschaft (ed.), Hamburg 2021, p. 62

Fig. 7: Embroidery sampler by M. Carolina, 1836. The embroidery sampler features the typical detailed and lifelike floral embroidery typical of the Biedermeier period, as well as the widespread motifs of monuments and temples in park-like landscapes. A girl in traditional is seen in the rural idyll of a village. A striking feature is the iron cross embroidered in the center with the crowned initials FW and the year 1813. The Prussian King Frederick William had donated the Iron Cross as an award for

services in the wars of liberation against Napoleon; on the sampler, it can be seen

as a political symbol for the desire for national unity. The sampler uses satin stitch, stem stitch, knot stitch, appliqué technique, and embroidered beads.-

https://collection.cooperhewitt.org/

objects/18616671/

services in the wars of liberation against Napoleon; on the sampler, it can be seen

as a political symbol for the desire for national unity. The sampler uses satin stitch, stem stitch, knot stitch, appliqué technique, and embroidered beads.-

https://collection.cooperhewitt.org/

objects/18616671/

Fig. 8: Embroidery sampler by Katharina Häusler, 1828. With the alphabets and numerals arranged in rows, the characteristic components of a sampler are still used here. The pictorial section contains typical Biedermeier elements: flowers, an ivy-covered urn as a symbol of friendship, and depictions of rural life with villages and hunting. The sampler is worked in cross-stitch.-

https://collection.cooperhewitt.org/

objects/18489081/

https://collection.cooperhewitt.org/

objects/18489081/

The development from spot samplers to so-called band samplers occurred earlier and more consistently in England than in Germany. German samplers from the 17th century are far fewer in number than English ones, which may be due to the destruction and devastation of the Thirty Years' War.[9] It appears that band samplers became popular in Germany later on. The number of band samplers and picture samplers was roughly equal. In the 18th century, band samplers predominated, but from the second third of the 18th century onwards, they very quickly gave way to picture formats. The development in Germany was therefore delayed in comparison with England in terms of form.

In contrast to English samplers, German embroidery samplers very rarely bear the name of the embroiderer; in Germany, it is more common to embroider initials and a year, but almost never the age of the embroiderer. By the end of the 18th century, only seven embroidery samplers with a name had been found.[10] This makes it difficult to determine conclusively whether the samplers were made by adults, young people, or schoolchildren. However, there are indications – albeit only slight ones – that, as in England, the production of samplers was intended to impart knowledge and was part of the education of girls: a sampler from 1723 depicts a scene from the Bible showing Hagar, who is pregnant by Abraham, fleeing from Abraham's wife, Sarah, and an angel appearing to her at a well. Hagar later became Abraham's second wife and bore his first son, Ishmael[11] . The depiction of the figures on the sampler is accompanied by the "caption" "Hagar" and "Ishmael." The figure of the angel is located between a tree and a branch; it is captioned "Der Fryling."[12] The meaning of this word is unclear; one might be tempted to recognize it as an earlier or dialectal form of the word "spring" if it were not for its earlier form, "Lenz." Assuming that it is an old dialect form of "Frühling," the inscription could refer to the fact that Ishmael became the progenitor of a confederation of twelve tribes of North Arabian peoples and, in this respect, represented a beginning, just like spring. Another possibility is to read "Der Fryling" as the title of the entire scene. In that case, the meaning could be that the story of the child Ishmael is being told, with "Fryling" meaning "the child." Whatever the exact meaning of the word may be, it can be assumed that it was clear to people in the 18th century. What is important here is that the caption or headline serves to clarify what is depicted in the image. Beginning with the embroiderer and ending with the viewers, the biblical story is conveyed in this way.

This intention to impart knowledge also seems to be present in an embroidery sampler from 1755. The sampler, which features many different motifs, shows a female figure with a crown in the upper left corner. She holds scales in one hand and a staff in the other. The caption "Iustitia" has been added, allowing for a clear interpretation of the figure. In the lower third of the cloth is a depiction of a male lion, recognizable by its mane, which is crowned and thus identified as the king of animals . The depiction is signed "Der Löwe". It is possible that the intention here was to commemorate this exotic animal[13] , as all the other animals on this sampler are native to the region and therefore familiar to both the embroiderer and the viewer.

This intention to impart knowledge also seems to be present in an embroidery sampler from 1755. The sampler, which features many different motifs, shows a female figure with a crown in the upper left corner. She holds scales in one hand and a staff in the other. The caption "Iustitia" has been added, allowing for a clear interpretation of the figure. In the lower third of the cloth is a depiction of a male lion, recognizable by its mane, which is crowned and thus identified as the king of animals . The depiction is signed "Der Löwe". It is possible that the intention here was to commemorate this exotic animal[13] , as all the other animals on this sampler are native to the region and therefore familiar to both the embroiderer and the viewer.

Fig. 9: Embroidery sampler from Saxony, 1723,

worked in cross stitch and satin stitch.-

https://skd-online-collection.skd.museum/

Details/Index/1231899

worked in cross stitch and satin stitch.-

https://skd-online-collection.skd.museum/

Details/Index/1231899

A sampler from 1763 may also provide a clue. In addition to numerous religious and secular motifs, its main motif depicts the main building of the Francke Foundations in Halle, which housed the orphanage founded in 1701.[14] It would be reasonable to assume that a girl living in this orphanage embroidered the cloth, i.e., that it was a product of the handicraft lessons taught there. There is another embroidery sampler from 1789 which – at least it is assumed – shows the main building of the Francke Foundations. However, " zahlreiche Eigenheiten [weisen] auf die Herkunft dieses Tuches aus einem herrschaftlichen Haus hin"[15] , so it is rather unlikely that this cloth was embroidered by a pupil in handicraft lessons at the orphanage.

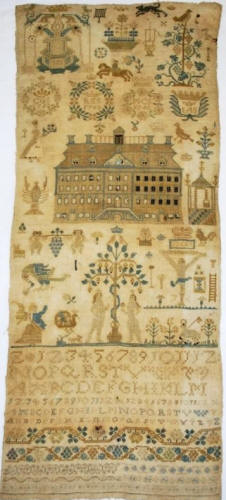

Fig. 10: Embroidery sampler, 1763. The main building of the

Franckesche Stiftungen in Halle/Saale is depicted in the center of the cloth. In addition, there are numerous Christian motifs: the crucifixion with the arma Christi, Adam and Eve, Joshua and Caleb, the Lamb of God, and the pelican. The cloth is worked in cross-stitch.-

https://nat.museum-digital.de/object/3107

Franckesche Stiftungen in Halle/Saale is depicted in the center of the cloth. In addition, there are numerous Christian motifs: the crucifixion with the arma Christi, Adam and Eve, Joshua and Caleb, the Lamb of God, and the pelican. The cloth is worked in cross-stitch.-

https://nat.museum-digital.de/object/3107

Fig. 11: Embroidery sampler with three dates: 1782, 1785, and 1789. Below the alphabets and numerals, there is a row of crowns, each each bear initials, suggesting that they can be attributed to specific nobles. The pictorial section features a spinning monkey, a basket of fruit, and a stork as symbols of fertility, the crucifixion scene framed by chairs and a table, a crab as a symbol of resurrection, Adam and Eve under the tree of knowledge, and Joshua and Caleb. The striking castle-like building probably represents the Francke Foundations in Halle.

The cloth is worked in cross-stitch.-

https://nat.museum-digital.de/object/763090

The cloth is worked in cross-stitch.-

https://nat.museum-digital.de/object/763090

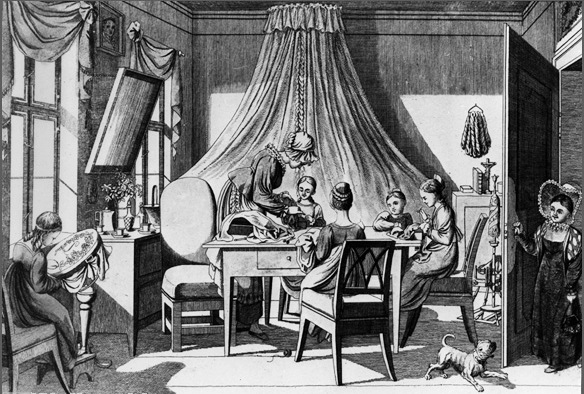

Other sources also provide no clear information as to whether German samplers were embroidered by adults in the 17th and 18th centuries or were created as part of girls' education. A Nuremberg household book from 1703 states that "das zarte Frauen-Zimmer und die jungen Mägdlein"[16] make samplers. In the "Nutzbares, galantes und curiöses Frauenzimmer-Lexicon" from 1715, it is said that " Jungfern in der Nehe-Schule" embroider samplers.[17] However, Zedler's Universal Lexicon from 1739 only mentions the "Frauenzimmer" making samplers, whereby the stated purpose of collecting "Buchstaben, allerley Figuren, Muster und so fort nach denen gar unterschiedenen Arten derer Stiche, soviel deren nur im Nähen vorkommen können"[18] does not allow any determination of the age of the embroiderers. Daniel Chodowiecki's copperplate engraving from 1774 shows young women doing household chores, including sewing and embroidery, with the spinning and embroidery being done by the "ladies" and the laundry being done by the maids. The cover pictures of the pattern books, which date from much earlier, also show young women embroidering.[19]

Fig. 12: Daniel Chodowiecki, Women's Work. Illustration for Johann Bernhard Basedow, Elementarwerk, 1744.- https://collections.lacma.org/node/232007

The illustrations on the title pages of the pattern books show that in the 16th and 17th centuries, women of the nobility and the wealthy bourgeoisie embroidered, and in the countryside, decorating objects with embroidery was a common activity in large households[20] . It can be safely assumed that in these social classes, daughters learned various handicrafts, including embroidery, at an early age and that they made samplers in the process. These were not only pattern collections, but also proof that the daughters' education had followed the recommendations and instructions of the virtues incorporated into the model books and that the result was " gehorsam[e], fleißig[e], keusch[e]"[21] and, above all, marriageable young ladies. In the 18th century, the image of women changed, leading above all to an expansion of embroidery circles and a change in the purpose of samplers. Although "noch in der ersten Hälfte des Jahrhunderts […] die Moralischen Wochenschriften das Bild der gelehrten Frau"[22] propagated and thus seemed to herald a departure from embroidery as a leisure activity in favor of the acquisition of knowledge and scholarly debate. However, this new Enlightenment understanding of roles was very quickly abandoned in favor of the view that women had a gender-specific destiny: it was divine will, nature itself, and society that excluded women from public life and confined them to domestic duties[23] . The general view was that scholarship only led to the neglect of female duties.

At the same time as this intellectual concept was developing, an actual social change was taking place, brought about by absolutist rule and mercantilist economics: the many small territories had a great need for revenue for representation, the army, and the administration, which they had to expand in order to enforce their rule everywhere. To this end, measures were taken to strengthen the economy of their own countries and thus increase revenues. The national economy, which was based on the principle of increasing revenues, was reflected in a change in private economic activity: it was no longer a matter of organizing production for the household's own needs and perhaps a small surplus, but rather "das Gewinnstreben begann, sich gegen die christliche Haushaltung durchzusetzen"[24] . Production for the market increased and new forms of production developed, such as publishing.

At the same time as this intellectual concept was developing, an actual social change was taking place, brought about by absolutist rule and mercantilist economics: the many small territories had a great need for revenue for representation, the army, and the administration, which they had to expand in order to enforce their rule everywhere. To this end, measures were taken to strengthen the economy of their own countries and thus increase revenues. The national economy, which was based on the principle of increasing revenues, was reflected in a change in private economic activity: it was no longer a matter of organizing production for the household's own needs and perhaps a small surplus, but rather "das Gewinnstreben begann, sich gegen die christliche Haushaltung durchzusetzen"[24] . Production for the market increased and new forms of production developed, such as publishing.

Fig. 13: Johann Heinrich Ramberg, Die gelehrte Frau (The Learned Woman), 1802. Ramberg illustrates the widespread view of the consequences that occur in a household when the housewife devotes herself to tasks other than housekeeping duties.-

https://wwwu.uni-klu.ac.at/elechner/schulmuseum/

wechselausstellung/wa01/wa01_04.htm

https://wwwu.uni-klu.ac.at/elechner/schulmuseum/

wechselausstellung/wa01/wa01_04.htm

The market-oriented focus of large estates and the introduction of new methods in agriculture and new products led to professionalization and thus to the dissolution of the "whole household." At the same time, the civil service grew, especially in the cities. The result was a restructuring of the family, as work increasingly took place outside the home. This eliminated the previous position of women as managers of the household. Both on large farms and in cities, women were now reduced to the home and family, in the narrow role of housewife and child-rearer. Their task was now to provide the man in the public eye with a harmonious and loving home where he could rest undisturbed from the hardships of work. However, women now had to perform tasks that "vorher gegen Bezahlung ausgeführt worden waren (Stillen, Kochen, Kinderversorgung und –erziehung, Kleiderpflege und –herstellung, Einkaufen, Putzen etc.). […]Die Übernahme der häuslichen Arbeit wurde zunehmend mit der Liebe zu Ehemann und Kindern begründet und eingefordert. Dazu trug auch das bürgerliche Ideal der Liebesheirat bei, das mit der Aufklärung und Romantik populär wurde: Da vordergründig nicht mehr aus rein ökonomischen Gründen geheiratet wurde, war die Ehefrau dazu verpflichtet, die häusliche Arbeit ohne Erwartung einer Gegenleistung als ´Liebesdienst´ zu versehen."[25] For bourgeois women, especially those of civil servants, there was the additional task of representing the family to the outside world[26] and establishing social contacts, i.e., building a network that could be helpful to their husbands' careers. This upward orientation also meant that it had to appear to the outside world as if the woman did not work herself, but had the leisure to pass the time with non-essential activities as a hobby. These activities were handicrafts, above all embroidery, because as an embellishing activity it most closely corresponded to the ideal image of the bourgeois housewife. In the middle and lower middle classes, the husband's income was often far from sufficient to enable his wife to live such a life.[27] Embroidery samplers, which in Germany from the mid-18th century onwards increasingly took on a pictorial format and also emphasized the pictorial elements, were ideally suited to be hung in a prominent place and to conceal the real living conditions of the family. At the same time, they served as proof of the virtues expected of a bourgeois housewife: "Aufmerksamkeit, Ordnung, Reinlichkeit, Fleiß, Sparsamkeit."[28] .

Fig. 14: Daniel Chodowiecki, The Family, 1771. Chodowiecki depicts his own family here. He sits at the window and goes about his work, while his wife is busy with the children gathered around the table.-

https://www.porta-polonica.de/de/atlas-der-erinnerungsorte/daniel-chodowiecki-die-polonica#lg=2&slide=1

https://www.porta-polonica.de/de/atlas-der-erinnerungsorte/daniel-chodowiecki-die-polonica#lg=2&slide=1

The acquisition of the skills required until the mid-19th century, when the first reliable household sewing machines came onto the market, to make all clothing and household linen by hand and, if necessary, to label and/or embellish it, took place in various ways. The Reformation took up the idea of the necessity of education that had already been developed during the Renaissance and modified it: education no longer served the goal of individual development, but rather had the goal of raising children to be good Christians.[29] Girls were expressly included in this, as they too should be able to read the Word of God. Luther therefore called on city rulers and princes to establish schools for both sexes[30] . In the Protestant states and cities of northern Germany, "relativ geordnete[n] Schulverhältnisse[n]" emerged[31] , which in several states were based on the church regulations of Johann Bugenhagen. They provided for a girls' school in every parish, for which parents had to pay school fees. For poor girls whose parents could not afford the school fees, the poor relief fund was to cover the cost. The girls were to learn to read, be taught religion, and learn Christian hymns. School attendance was to be one, at most two hours a day. All other skills necessary for housekeeping were to be acquired at home. The aim was to train "nützliche, fröhliche, geschickte, freundliche, gehorsame, gottesfürchtige, nicht abergläubische und eigensinnige Hausmütter, die ihr Haus in Zucht regieren und die Kinder in Gehorsam, Ehr- und Gottesfurcht auferziehen"

[32]. The literature indicates that a two-tier school system was established for girls: for young girls, there was the so-called Dirnckens Schol, which was compulsory and served the above-mentioned elementary education. For girls between the ages of 9 and 14, there was the Jungfern Schol, which was not compulsory but strongly recommended. This school provided instruction in needlework.[33] It is difficult to determine how widespread these schools actually were, but it is said that "in den Städten […], auch in den wohlhabenden Landgebieten, den Vierlanden, dem Alten Land, der Wilstermarsch, der Probstei etwa, um nur Beispiele zu nennen, […] diese Schulen allemal vorhanden waren."

[34]

However, there is no uniform picture for the area of present-day Germany or even the German-speaking region, because the fragmentation into a multitude of small territories ruled this out. Literature refers to a school for poor girls in the convent of the Penitents of St. Jerome in 1569, where the girls were taught "Religion, Lesen, Schreiben sowie in Hand- und Haushaltsarbeiten“[35] . From the middle of the 17th century, religious orders also became involved in the education and training of children. One well-known example is the Ursuline Order, which generally offered free elementary schooling for poor girls and boarding schools for the daughters of the nobility and bourgeoisie. The curriculum of the Ursuline elementary schools included the same subjects as that of the penitents of St. Jerome. In 1684, for example, such a school was established in Düsseldorf.[36]

A very well-known example of girls' education is the Francke Foundations in Halle, which were founded in 1698. In addition to other types of schools, there was also an elementary school. In 1710, Francke established the curriculum for girls, in which reading, writing, and religion played a prominent role. "Für die Maedgen ist auch darinn gesorgt, daß ihnen eigene Lehrerinnen im Nähen, Stricken und Sticken gehalten werden."[37] The fame of this school and its concept, which focused on the individual talents of each child, contributed to its great popularity, especially in Pietist circles, which may have led to the motif of the orphanage on the above-mentioned embroidery samplers.

A very well-known example of girls' education is the Francke Foundations in Halle, which were founded in 1698. In addition to other types of schools, there was also an elementary school. In 1710, Francke established the curriculum for girls, in which reading, writing, and religion played a prominent role. "Für die Maedgen ist auch darinn gesorgt, daß ihnen eigene Lehrerinnen im Nähen, Stricken und Sticken gehalten werden."[37] The fame of this school and its concept, which focused on the individual talents of each child, contributed to its great popularity, especially in Pietist circles, which may have led to the motif of the orphanage on the above-mentioned embroidery samplers.

Fig. 15: Johann Michael Voltz, Häusliches Handarbeiten, 1823.- https://germanhistorydocs.ghi-dc.org/sub_image.cfm?image_id=298

However, it must be assumed that, despite the establishment of these schools, a large proportion of girls from the upper classes continued to be educated at home and prepared for their traditional roles as wives and mothers. There were higher schools for girls, such as the Augustinian school "Beatae Mariae Virginis" in Essen, founded in 1652, but if girls from noble or wealthy families were not taught at home by private tutors or governesses, they usually attended a girls' boarding school. There they were "befähigt […], als zukünftige Gattin eines wohlhabenden Mannes einem vornehmen Haushalt vorstehen zu können und einen Salon zu führen. Die Vorbereitung auf einen praktischen Beruf oder das Erwerbsleben war nicht vorgesehen. Im Handarbeitsunterricht erlernten sie die feinen Handarbeiten".[38]

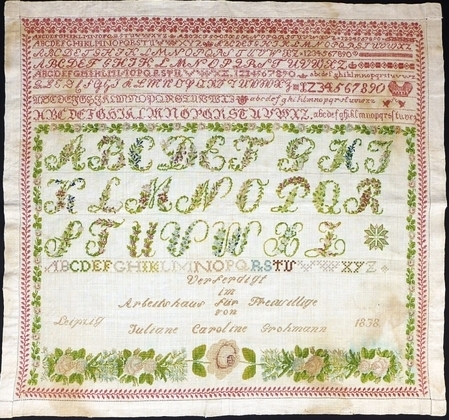

Since the 1830s, the elements of embroidery samplers have changed: now place names and inscriptions such as "Zum Andenken an die Schulzeit" or "Andenken meiner Jugend" appear, and from the 1850s onwards, it became standard practice to include the name of the embroiderer. At the same time, the proportion of samplers with a large number of pictorial elements declined in favor of very simple samplers that only featured one or more alphabets, the numbers from one to ten, and the name of the embroiderer, occasionally also various crowns. This change can be attributed to the expansion of compulsory schooling and its increasing enforcement in individual states. The general compulsory education introduced in 1717 by King Frederick William I of Prussia and its implementation by Frederick II's General School Regulations for Elementary Schools in 1763 represented progress, but in reality it was not always enforced. In 1794, the General Prussian Land Law regulated the school system: schools became a matter for the state and were placed under its supervision; however, parents were allowed to teach and educate their children at home.[39] There were no state regulations regarding content, so the churches continued to determine the curricula. Prussia's defeat at Jena and Auerstedt in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars led to the so-called Prussian reforms from 1807 onwards, which also included an education reform, although this only affected grammar schools. As far as elementary schools were concerned, the school attendance rate "[wurde] zu Beginn des 19. Jahrhunderts auf 60 Prozent geschätzt, von 2,2 Millionen nach dem Gesetz schulpflichtigen Kindern besuchten nicht mehr als 1,3 Millionen eine Schule […] [Allerdings] betrug der durchschnittliche Schulbesuch in Preußen 1846 schon etwa 86 Prozent."[40] The subjects taught also included handicrafts: In 1817 and again in 1830 in Prussia, handicrafts were included in the curriculum[41]. "Um die Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts verstärkten sich in verschiedenen Landesteilen die Bemühungen um die obligatorische Einführung eines systematischen Handarbeitsunterrichts"[42] , and "Vertreter von Industrieschulvereinen machten z. B. für Mecklenburg einen ganzen Katalog von Forderungen auf: 1. »Der Handarbeitsunterricht sollte an allen Schulen obligatorisch sein«; 2. der »Handarbeitsunterricht sollte Massenunterricht sein […] und stufenmäßig nach einem geordneten Plan fortschreiten«10. Parallel zu diesen formalen Forderungen nach Disziplinierung wurden durchaus auch inhaltliche Ansprüche der kreativen Vermittlung erhoben: »die rein mechanische Nacharbeit ist zu verwerfen – denn Handarbeit ist eine geistig durchdachte Arbeit, […] die Auswahl der Arbeiten sollten an der Brauchbarkeit fürs praktische Leben orientiert sein"[43] . In addition to the establishment of schools in the German states, in a time of increasing pauperism, it was also helpful to fall back on the tradition of work schools, which had existed since the 17th century, and the industrial schools that emerged towards the end of the 18th century, "in denen die Bedürftigen beschäftigt wurden und zugleich eine Arbeit erlernten, die ihnen eine Existenzgrundlage ermöglichen sollte."[44] One example is the poorhouse in Göttingen, which was modernized in 1818/19 with the aim of providing volunteers with space, materials, and tools so that they could carry out manual work.[45]

Since the 1830s, the elements of embroidery samplers have changed: now place names and inscriptions such as "Zum Andenken an die Schulzeit" or "Andenken meiner Jugend" appear, and from the 1850s onwards, it became standard practice to include the name of the embroiderer. At the same time, the proportion of samplers with a large number of pictorial elements declined in favor of very simple samplers that only featured one or more alphabets, the numbers from one to ten, and the name of the embroiderer, occasionally also various crowns. This change can be attributed to the expansion of compulsory schooling and its increasing enforcement in individual states. The general compulsory education introduced in 1717 by King Frederick William I of Prussia and its implementation by Frederick II's General School Regulations for Elementary Schools in 1763 represented progress, but in reality it was not always enforced. In 1794, the General Prussian Land Law regulated the school system: schools became a matter for the state and were placed under its supervision; however, parents were allowed to teach and educate their children at home.[39] There were no state regulations regarding content, so the churches continued to determine the curricula. Prussia's defeat at Jena and Auerstedt in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars led to the so-called Prussian reforms from 1807 onwards, which also included an education reform, although this only affected grammar schools. As far as elementary schools were concerned, the school attendance rate "[wurde] zu Beginn des 19. Jahrhunderts auf 60 Prozent geschätzt, von 2,2 Millionen nach dem Gesetz schulpflichtigen Kindern besuchten nicht mehr als 1,3 Millionen eine Schule […] [Allerdings] betrug der durchschnittliche Schulbesuch in Preußen 1846 schon etwa 86 Prozent."[40] The subjects taught also included handicrafts: In 1817 and again in 1830 in Prussia, handicrafts were included in the curriculum[41]. "Um die Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts verstärkten sich in verschiedenen Landesteilen die Bemühungen um die obligatorische Einführung eines systematischen Handarbeitsunterrichts"[42] , and "Vertreter von Industrieschulvereinen machten z. B. für Mecklenburg einen ganzen Katalog von Forderungen auf: 1. »Der Handarbeitsunterricht sollte an allen Schulen obligatorisch sein«; 2. der »Handarbeitsunterricht sollte Massenunterricht sein […] und stufenmäßig nach einem geordneten Plan fortschreiten«10. Parallel zu diesen formalen Forderungen nach Disziplinierung wurden durchaus auch inhaltliche Ansprüche der kreativen Vermittlung erhoben: »die rein mechanische Nacharbeit ist zu verwerfen – denn Handarbeit ist eine geistig durchdachte Arbeit, […] die Auswahl der Arbeiten sollten an der Brauchbarkeit fürs praktische Leben orientiert sein"[43] . In addition to the establishment of schools in the German states, in a time of increasing pauperism, it was also helpful to fall back on the tradition of work schools, which had existed since the 17th century, and the industrial schools that emerged towards the end of the 18th century, "in denen die Bedürftigen beschäftigt wurden und zugleich eine Arbeit erlernten, die ihnen eine Existenzgrundlage ermöglichen sollte."[44] One example is the poorhouse in Göttingen, which was modernized in 1818/19 with the aim of providing volunteers with space, materials, and tools so that they could carry out manual work.[45]

Fig. 16: Embroidery sampler by Juliane Caroline Grohmann, 1832. The cloth was made using cross-stitch in the workhouse for volunteers in Leipzig. In workhouses, the poor and orphans were occasionally volunteers were taught skills that would enable them to find work.-

https://nat.museum-digital.de/object/929542

https://nat.museum-digital.de/object/929542

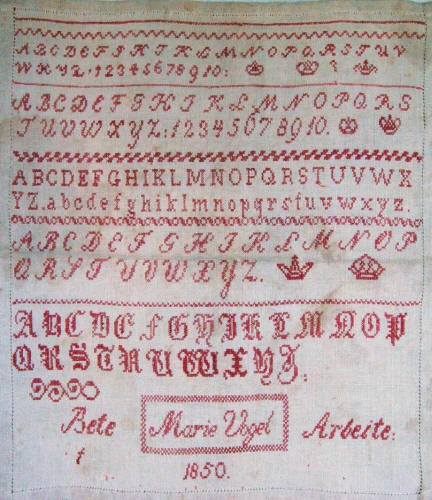

Fig. 17: Embroidery sampler by Marie Vogel, 1850.

The inscription "Bete - Arbeite," which frames the name of the embroiderer, suggests that this sampler was made in a school that specifically prepared young girls for a profession. The cloth was embroidered in cross-stitch and already uses the typical red embroidery color.-

https://skd-online-collection.skd.museum/Details/Index/747164

The inscription "Bete - Arbeite," which frames the name of the embroiderer, suggests that this sampler was made in a school that specifically prepared young girls for a profession. The cloth was embroidered in cross-stitch and already uses the typical red embroidery color.-

https://skd-online-collection.skd.museum/Details/Index/747164

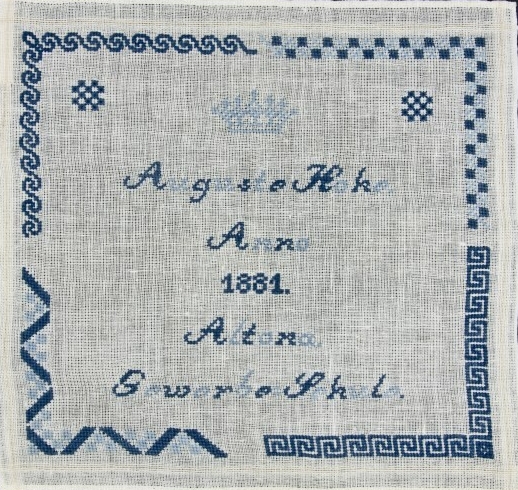

Fig. 18: Embroidery sampler by Auguste Hoke, 1881. The cloth was made at the Altona vocational school. It is cross-stitch.-

https://www.museen-sh.de/Objekt/DE-MUS-058811/lido/alt-e00025194

https://www.museen-sh.de/Objekt/DE-MUS-058811/lido/alt-e00025194

Fig. 19: Embroidery sampler, 1902. The sampler was made by a student at the Gmünd Industrial School using cross-stitch. The squares at the bottom are exercises in darning and mending.-

In the course of the Kulturkampf, the church lost its influence on the content of school lessons. Instead, the state introduced regulations for school subjects and their content with the "General Provisions" of 1872. Handicraft lessons "sollte[n] mindestens zwei Stunden pro Woche von einer dafür qualifizierten Handarbeitslehrerin erteilt werden. Der Lehrplan sah ausschließlich die so genannten ´Nutzarbeiten´ vor. Damit sollten später alle im Haushalt anfallenden Arbeiten ausgeführt werden können. Dazu gehörten das Strumpfstricken, Übungen am Zeichentuch (das Sticken) und Nähtuch (Ausführen verschiedener Nähte), das Nähen eines Frauenhemdes, Flicken und Stopfen (Ausbessern)."[46] The aim was to prepare the girls for their future role as housewives so that they would be able to "die Textilien in den Familien so auszubessern, dass sie dem ´bürgerlichen Anspruch´ nach Ordnung und Sauberkeit entsprachen."[47]

For girls from the lower social classes, needlework lessons provided the basis for their work: "Viele arbeiteten als Näherinnen in gut gestellten Familien und in kleinen Gewerbebetrieben, nähten dort nach Auftrag, besserten aus, fertigten Aussteuern. Für Berlin wird die Zahl dieser Arbeitskräfte für das Jahr um 1885 auf cirka 103.000 Frauen angegeben."[48] This purpose is also evident in the crowns often found on samplers, as the ability to embroider them was required if a girl found employment in a noble household[49] . At the same time, needlework lessons served to "Einübung bürgerlicher Tugenden wie Ordnung, Fleiß, Sparsamkeit, Geduld sowie Strebsamkeit und [trug] somit zur ´Erziehung zur Weiblichkeit`"[50] . The curricula—and here in particular the influence of Rosalie Schallenfeld, headmistress of a girls' secondary school in Berlin, who developed and promoted a curriculum for needlework lessons[51] —contributed to the disappearance of individual designs on embroidery samplers. Instead, they were given a standardized appearance: "auf mäßig feinem Stramin [wurde] mit türkisch-rotem Garn […] Systematisch[…] auf den Kreuzstich hingearbeitet, am oberen Rand werden einfache gerade Stiche geübt, dann folgen schräge Stiche, die zum Kreuzstich hinführen, der nach dieser Übung erst zu Buchstaben verarbeitet wird. […] Als Ersatz für Blumenmotive werden zu Ende des Jahrhunderts häufiger den Buchstabenreihen kurze Sprüche angefügt – „Alles mit Gott so hats keine Not“, Sprüche, wie sie zu dieser Zeit für Überhandtücher und Wandschoner modisch."[52] Handicraft lessons were taught by handicraft teachers who, from 1887 onwards, had to pass a practical and theoretical examination in order to be accepted into the civil service.[53]

For girls from the lower social classes, needlework lessons provided the basis for their work: "Viele arbeiteten als Näherinnen in gut gestellten Familien und in kleinen Gewerbebetrieben, nähten dort nach Auftrag, besserten aus, fertigten Aussteuern. Für Berlin wird die Zahl dieser Arbeitskräfte für das Jahr um 1885 auf cirka 103.000 Frauen angegeben."[48] This purpose is also evident in the crowns often found on samplers, as the ability to embroider them was required if a girl found employment in a noble household[49] . At the same time, needlework lessons served to "Einübung bürgerlicher Tugenden wie Ordnung, Fleiß, Sparsamkeit, Geduld sowie Strebsamkeit und [trug] somit zur ´Erziehung zur Weiblichkeit`"[50] . The curricula—and here in particular the influence of Rosalie Schallenfeld, headmistress of a girls' secondary school in Berlin, who developed and promoted a curriculum for needlework lessons[51] —contributed to the disappearance of individual designs on embroidery samplers. Instead, they were given a standardized appearance: "auf mäßig feinem Stramin [wurde] mit türkisch-rotem Garn […] Systematisch[…] auf den Kreuzstich hingearbeitet, am oberen Rand werden einfache gerade Stiche geübt, dann folgen schräge Stiche, die zum Kreuzstich hinführen, der nach dieser Übung erst zu Buchstaben verarbeitet wird. […] Als Ersatz für Blumenmotive werden zu Ende des Jahrhunderts häufiger den Buchstabenreihen kurze Sprüche angefügt – „Alles mit Gott so hats keine Not“, Sprüche, wie sie zu dieser Zeit für Überhandtücher und Wandschoner modisch."[52] Handicraft lessons were taught by handicraft teachers who, from 1887 onwards, had to pass a practical and theoretical examination in order to be accepted into the civil service.[53]

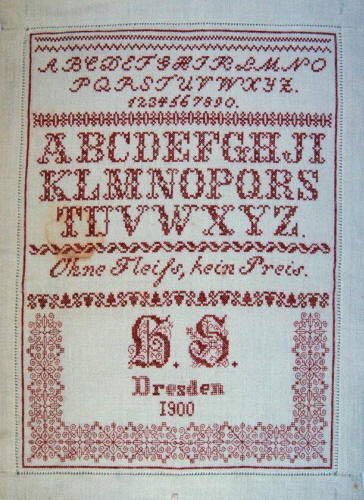

Fig. 20: Embroidery sampler, Dresden 1900. The upper part of this embroidery sampler is typical of school samplers from 1872 onwards. The second alphabet and the half-circular border represent advanced work. The saying is typical of the late 19th/early 20th century.-

https://skd-online-collection.skd.museum/

Details/Index/748210

https://skd-online-collection.skd.museum/

Details/Index/748210

Fig. 21: Parts from the tablecloth made by my handicrafts teacher in elementary school,

Ms. Elisabeth Scharenberg, as an exam piece.

Ms. Scharenberg was about to retire in 1960.

(own photo)

Ms. Elisabeth Scharenberg, as an exam piece.

Ms. Scharenberg was about to retire in 1960.

(own photo)

Another difference between English and German samplers, which is significant for the history of cross-stitch, is the types of stitches used on samplers and embroidery samplers. The German embroidery sampler from the first half of the 16th century mentioned above mainly uses cross-stitch, with a much smaller amount of braid stitch. The few embroidery samplers from the 17th century that have survived are mainly embroidered in simple cross stitch or its variants (Montenegrin and Italian cross stitch); there are small amounts of back stitch, running stitch, stem stitch, and satin stitch. From the 18th century onwards, cross-stitch became the stitch of choice for embroidery samplers. Other stitches are so rare that they are hardly worth mentioning; most of them are backstitches or stem stitches used to border motifs. Cross-stitch thus became the standard stitch in embroidery in Germany much earlier than in England.

Bergemann points out that cross-stitch was already known in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, but was rarely used. However, it "in der zweiten Hälfte des 16. Jahrhunderts […] mit dem Aufkommen der farbig ausgestickten Kanevasstickereien [habe er] rasch an Bedeutung [gewonnen]"[54] . This development was probably supported by the emergence of pattern books, which presented their patterns as drawings on a grid, making them particularly suitable for canvas embroidery. As early as 1703, a Nuremberg household book highlighted cross-stitch and named it as the stitch for embroidery samplers, "weil das zarte kleinen Frauen-Zimmer und die jungen Maegdlein darinnen am allerersten pflegen angewiesen zu werden/und bey uns davon besondere Model-Tuecher zu machen."[55] The popularity of cross-stitch is also evident from the statement "so machen man auch von diesen Stich groß und kleine Kissen/SpielBeutel/Kammfuter/und allerley Galanterien"[56] . The fact that cross-stitch was widely established is shown by the entry in Covinus' Frauenzimmer-Lexikon from 1715, which states under the keyword "Creutz-Nahd or Creutz-Stich": "Ist eine sonderbahre Art, die Nahmen, Jahrzahl, auch offters gantze Figuren in weisse Wäsche, durch eitel Creutz-Stiche, so über den Faden gezehlet werden, Creutz-weiß einzuziehen"[57] and cross-stitch is explicitly mentioned as an embroidery technique for samplers: "worinnen (gemeint: im Modell-Tuch, d.Verf.) das Weibes-Volck die Creutz-Nahd an Buchstaben, Zahlen und allerhand Figuren entworffen, und welches denen Jungfern in der Nehe-Schule zur Vorschrifft vorgeleget wird."[58] This assessment of the importance of cross-stitch remained unchanged until the beginning of the 19th century, as can be seen from Löffler's instructions for women's work from 1826. There it states that "unter dem bunten Genähe […] vordersamst der Kreuzstich zu bemerken [ist] […] der bey uns vorzüglich zur Verfertigung der sogenannten Modeltücher gebraucht [wird]" [59]. In view of this development, it is not surprising that needlework lessons also began with the easy-to-learn cross-stitch and only then moved on to the more difficult satin stitch.[60]

The Damen Conversations Lexikon of 1837 already considers cross-stitch to be historical when it states that it was frequently used in tapestry embroidery—presumably referring to embroideries in the Berlin Wool Work style —but then faded into the background in favor of petit point stitching. In contrast to other embroidery techniques, which would then be more likely to be classified as needle painting, the encyclopedia judges that "der petit point, oder auch der Kreuzstich, die Gunst der Mehrzahl [genießt], die nichts von Malerei versteht, was bei sämmtlichen, kunstreichern, freien Stickereien durchaus nöthig ist."[61] The disparagement of cross-stitch as non-artistic, which is evident here, was obviously widespread in the 19th century, as Falke describes it as "die bevorzugte Manier unserer Tage, ja heute von der Dilettantenhand fast allein geübt"[62] . He sees the cross-stitch technique as imperfect and "künstlerisch […] unangemessen, weil sie im Grund nur Karrikaturen hervorzubringen im Stande ist"[63] . Therefore, cross-stitch is " allein für Ornamente in geraden Linien, für geometrisch-musivische Muster [geeignet]"[64] . Cross-stitch requires only "ein bischen Zählen, ein gutes Auge, eine sichere Hand – das ist alles. Es ist also nur eine Beschäftigung, ein Zeitvertreib übrig geblieben, aber keine Kunst."[65] . These assessments make it clear that the deprofessionalization of embroidery and its widespread popularity among the aristocracy and bourgeoisie as well as the fashionable Berlin Wool Work are seen as the reason for the preference for cross-stitch and thus the degradation of embroidery as lacking in aesthetics, creativity, and artistic intention. This view can also be found—albeit only in one sentence of a more extensive article—in Brockhaus Konversations-Lexikon at the end of the 19th century, where it states that "zu Anfang unseres Jahrhunderts […] die Stickkunst einen tiefen Stand erreicht hat"[66] and only "dank der kunstgewerblichen Bewegung (gemeint: die arts and crafts-Bewegung, d. Verf.) seit den sechziger Jahren“[67], it had regained its quality since the 1860s, to which the art embroidery schools that emerged in Prussia, Saxony, and especially Austria in the wake of this movement made a significant contribution by "dem erwachsenen weiblichen Geschlecht eine rationelle Ausbildung in der Weiß- und Buntstickerei [zu] gewähren"[68] .

In the wake of progressive education efforts, the production of embroidery samplers was removed from needlework classes at the turn of the century, as embroidery was now to be limited to useful items[69] . Examples include the production of needle cases or cutlery pouches, which were still being embroidered in the lower grades of elementary school (now primary school) in the 1950s. Progressive education represents the end of a development with regard to embroidery samplers that had already been slowly taking place throughout the 19th century. The advent of embroidery patterns, which could be purchased individually or borrowed, played a significant role in the demise of embroidery samplers.[70] Due to their low price, these patterns made samplers obsolete. A women's encyclopedia from 1846 states that the "Modelltuch, ehedem das unumgängliche Erforderniss, um junge Mädchen das sogenannte Buchstaben-Bezeichnen der Wäsche zu lehren […] in langweilige, Zeit und Seide verschwendende Spielerei aus[artete]."[71] Another contributing factor was the invention of the embroidery machine, which became widely available in the 1880s and replaced hand embroidery in many areas[72] , so that, together with the sewing machine and the knitting machine, there was increasing mechanization and industrialization of activities that had previously been carried out by women in their homes.

All in all, it is obvious, that, despite the critisicm, the popularity of the embroidery patterns led to a huge increase in the number of women taking up embroidery done in cross stitch or its deviations, but the quality of the work was not always guaranteed, with the result that the general public ultimately condemned the depictions of rural idylls and scenes from times long past as artificial nostalgia.[73]

Bergemann points out that cross-stitch was already known in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, but was rarely used. However, it "in der zweiten Hälfte des 16. Jahrhunderts […] mit dem Aufkommen der farbig ausgestickten Kanevasstickereien [habe er] rasch an Bedeutung [gewonnen]"[54] . This development was probably supported by the emergence of pattern books, which presented their patterns as drawings on a grid, making them particularly suitable for canvas embroidery. As early as 1703, a Nuremberg household book highlighted cross-stitch and named it as the stitch for embroidery samplers, "weil das zarte kleinen Frauen-Zimmer und die jungen Maegdlein darinnen am allerersten pflegen angewiesen zu werden/und bey uns davon besondere Model-Tuecher zu machen."[55] The popularity of cross-stitch is also evident from the statement "so machen man auch von diesen Stich groß und kleine Kissen/SpielBeutel/Kammfuter/und allerley Galanterien"[56] . The fact that cross-stitch was widely established is shown by the entry in Covinus' Frauenzimmer-Lexikon from 1715, which states under the keyword "Creutz-Nahd or Creutz-Stich": "Ist eine sonderbahre Art, die Nahmen, Jahrzahl, auch offters gantze Figuren in weisse Wäsche, durch eitel Creutz-Stiche, so über den Faden gezehlet werden, Creutz-weiß einzuziehen"[57] and cross-stitch is explicitly mentioned as an embroidery technique for samplers: "worinnen (gemeint: im Modell-Tuch, d.Verf.) das Weibes-Volck die Creutz-Nahd an Buchstaben, Zahlen und allerhand Figuren entworffen, und welches denen Jungfern in der Nehe-Schule zur Vorschrifft vorgeleget wird."[58] This assessment of the importance of cross-stitch remained unchanged until the beginning of the 19th century, as can be seen from Löffler's instructions for women's work from 1826. There it states that "unter dem bunten Genähe […] vordersamst der Kreuzstich zu bemerken [ist] […] der bey uns vorzüglich zur Verfertigung der sogenannten Modeltücher gebraucht [wird]" [59]. In view of this development, it is not surprising that needlework lessons also began with the easy-to-learn cross-stitch and only then moved on to the more difficult satin stitch.[60]

The Damen Conversations Lexikon of 1837 already considers cross-stitch to be historical when it states that it was frequently used in tapestry embroidery—presumably referring to embroideries in the Berlin Wool Work style —but then faded into the background in favor of petit point stitching. In contrast to other embroidery techniques, which would then be more likely to be classified as needle painting, the encyclopedia judges that "der petit point, oder auch der Kreuzstich, die Gunst der Mehrzahl [genießt], die nichts von Malerei versteht, was bei sämmtlichen, kunstreichern, freien Stickereien durchaus nöthig ist."[61] The disparagement of cross-stitch as non-artistic, which is evident here, was obviously widespread in the 19th century, as Falke describes it as "die bevorzugte Manier unserer Tage, ja heute von der Dilettantenhand fast allein geübt"[62] . He sees the cross-stitch technique as imperfect and "künstlerisch […] unangemessen, weil sie im Grund nur Karrikaturen hervorzubringen im Stande ist"[63] . Therefore, cross-stitch is " allein für Ornamente in geraden Linien, für geometrisch-musivische Muster [geeignet]"[64] . Cross-stitch requires only "ein bischen Zählen, ein gutes Auge, eine sichere Hand – das ist alles. Es ist also nur eine Beschäftigung, ein Zeitvertreib übrig geblieben, aber keine Kunst."[65] . These assessments make it clear that the deprofessionalization of embroidery and its widespread popularity among the aristocracy and bourgeoisie as well as the fashionable Berlin Wool Work are seen as the reason for the preference for cross-stitch and thus the degradation of embroidery as lacking in aesthetics, creativity, and artistic intention. This view can also be found—albeit only in one sentence of a more extensive article—in Brockhaus Konversations-Lexikon at the end of the 19th century, where it states that "zu Anfang unseres Jahrhunderts […] die Stickkunst einen tiefen Stand erreicht hat"[66] and only "dank der kunstgewerblichen Bewegung (gemeint: die arts and crafts-Bewegung, d. Verf.) seit den sechziger Jahren“[67], it had regained its quality since the 1860s, to which the art embroidery schools that emerged in Prussia, Saxony, and especially Austria in the wake of this movement made a significant contribution by "dem erwachsenen weiblichen Geschlecht eine rationelle Ausbildung in der Weiß- und Buntstickerei [zu] gewähren"[68] .

In the wake of progressive education efforts, the production of embroidery samplers was removed from needlework classes at the turn of the century, as embroidery was now to be limited to useful items[69] . Examples include the production of needle cases or cutlery pouches, which were still being embroidered in the lower grades of elementary school (now primary school) in the 1950s. Progressive education represents the end of a development with regard to embroidery samplers that had already been slowly taking place throughout the 19th century. The advent of embroidery patterns, which could be purchased individually or borrowed, played a significant role in the demise of embroidery samplers.[70] Due to their low price, these patterns made samplers obsolete. A women's encyclopedia from 1846 states that the "Modelltuch, ehedem das unumgängliche Erforderniss, um junge Mädchen das sogenannte Buchstaben-Bezeichnen der Wäsche zu lehren […] in langweilige, Zeit und Seide verschwendende Spielerei aus[artete]."[71] Another contributing factor was the invention of the embroidery machine, which became widely available in the 1880s and replaced hand embroidery in many areas[72] , so that, together with the sewing machine and the knitting machine, there was increasing mechanization and industrialization of activities that had previously been carried out by women in their homes.

All in all, it is obvious, that, despite the critisicm, the popularity of the embroidery patterns led to a huge increase in the number of women taking up embroidery done in cross stitch or its deviations, but the quality of the work was not always guaranteed, with the result that the general public ultimately condemned the depictions of rural idylls and scenes from times long past as artificial nostalgia.[73]