Samplers

Even before the first pattern book with embroidery designs was published in 1523, there were collections of embroidery designs, but these were not traded as marketable goods. Instead, they were produced by a single person, remained in their possession, and, at best, were passed down from generation to generation within a family.[1] Pieces – possibly remnants – of a base fabric were embroidered with patterns wherever there was space, which is why these cloths were called "random or spot samplers".[2] It is assumed that these samplers were made by experienced, if not professional, embroiderers[3] to be stored rolled up[4] and used as reference pieces for future embroidery.[5] Not only were their own patterns "saved," but patterns from others were also copied,[6] and new patterns were probably added again and again[7] . In addition, these collections not only offered patterns, like the model books, but also "stored" a variety of embroidery techniques, including cross-stitch[8] , so that the effect of the patterns could be seen and it was also possible to understand how the embroidery stitch was made by unraveling the embroidery[9] . Samplers also made it possible to demonstrate visual effects created by the variety of colors and their combinations, as well as by the use of different embroidery threads.[10] The term "sampler" for these embroidery pattern cloths originated in England and arose from their character as a "notebook" or "notepad" – hence the derivation from the Latin "exemplum" or the French "exemple"[11]. In the Netherlands, they were called "merklappen," in German-speaking countries "Modeltücher," and in Italian "imparaticci."[12] Combined with the fact that embroidery was obviously practiced by untrained people in a domestic setting, it was this purpose of samplers that led to embroidery suffering a loss of prestige since the 16th century, as it was no longer seen as an art but as a craft.[13]

Since samplers contributed significantly to the spread of cross-stitch, it is appropriate to take a look at their development and the context in which they evolved. Of the many subtypes of samplers, which are seen as "wichtige[n] textile[n] Ausdrucks- und Tradierungsform"[14], only those samplers that served as embroidery samplers will be considered here.

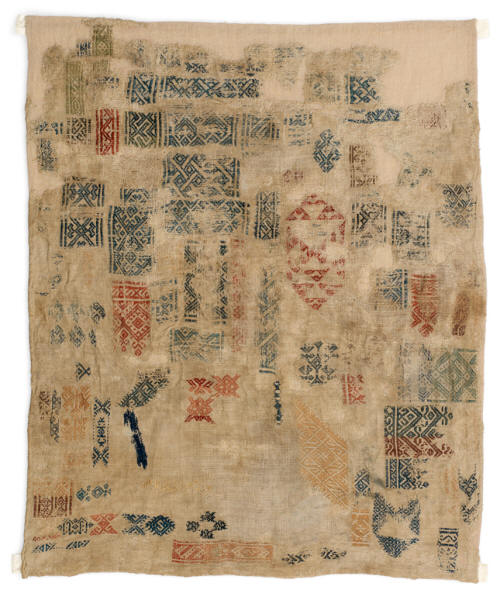

The literature states that the "älteste bekannte Stickmustertuch […]aus dem 9. Jahrhundert aus Zentralasien [stamme]"[15] . Embroidery samplers from Egypt dating from between the 13th and 16th centuries have been preserved.[16] In the 16th century, embroidery samplers were a pan-European phenomenon, although it remains unclear whether they or the idea behind them came to Europe through trade or whether they are a European tradition for which there is simply no older surviving evidence.

The existence of samplers around the year 1500 can be proven for England by a source that also uses the term sampler: For the year 1502, the household accounts of Queen Elizabeth of York note that on July 10, Thomas Fisshe was paid 8d for, among other things, "an elne of Iynnyn cloth for a sampler for the Quene"[17], and King Edward VI's inventory from 1552 mentions a "sampler or set of patterns workes on Normandy canvas with green and black silks"[18]. It is known that samplers were considered valuable possessions and were often mentioned in wills[19], such as "1546, [when] Margaret Thompson, of Freston-in-Holland, Lincolnshire, left a will, in which she says, 'I gyve to Alys Pynchebeck my syster's doughter my sawmpler with semes.'“[20] There is also literary evidence of the widespread use of samplers[21]. The term 'modeltücher' appears in a German text from 1562[22], and the Dutch painter Joos van Cleve depicts a sampler in a version of his painting 'The Holy Family' created around 1520.[23]

The existence of samplers around the year 1500 can be proven for England by a source that also uses the term sampler: For the year 1502, the household accounts of Queen Elizabeth of York note that on July 10, Thomas Fisshe was paid 8d for, among other things, "an elne of Iynnyn cloth for a sampler for the Quene"[17], and King Edward VI's inventory from 1552 mentions a "sampler or set of patterns workes on Normandy canvas with green and black silks"[18]. It is known that samplers were considered valuable possessions and were often mentioned in wills[19], such as "1546, [when] Margaret Thompson, of Freston-in-Holland, Lincolnshire, left a will, in which she says, 'I gyve to Alys Pynchebeck my syster's doughter my sawmpler with semes.'“[20] There is also literary evidence of the widespread use of samplers[21]. The term 'modeltücher' appears in a German text from 1562[22], and the Dutch painter Joos van Cleve depicts a sampler in a version of his painting 'The Holy Family' created around 1520.[23]

Fig. 1: Joos van Cleve (c. 1485-1540/41), The Holy Family, created around 1520, Currier Museum of Art, Manchester, New Hampshire, USA.- https://collections.currier.org/objects-1/info/242

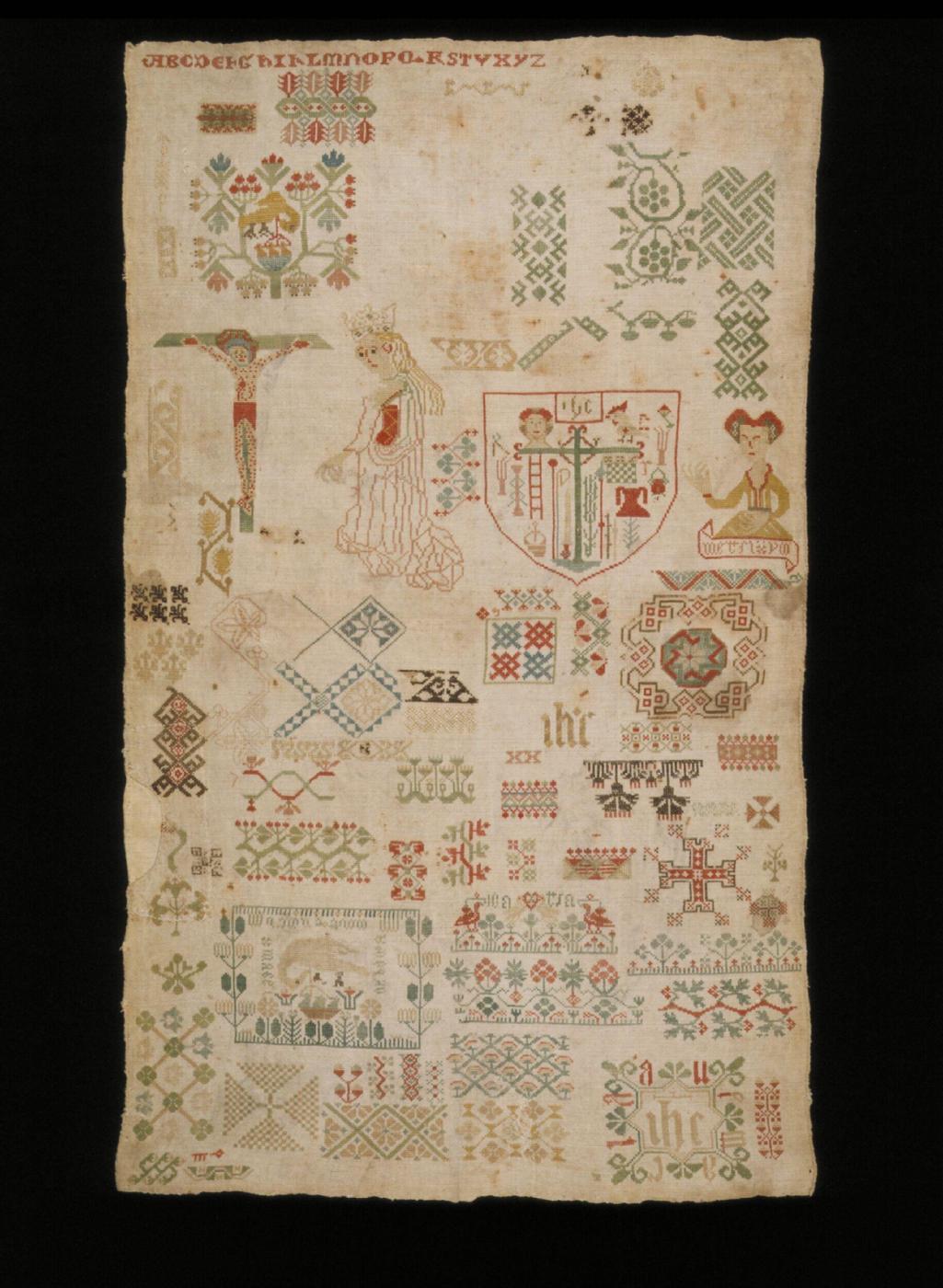

The Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge has a sampler that is thought to be from the 15th century, based on how similar the geometric patterns are to ones you see on clothes and household linens from that time.[24] Like an embroidery sampler from Germany dated to the first half of the 16th century, it is designed as a spot sampler; embroidered in cross-stitch and braid stitch, the sampler features Christian motifs alongside an alphabet and decorative patterns.[25] Very few samplers from the 16th century have survived. As mentioned above, it can be assumed that older samplers have all been lost. However, the rarity of these old samplers could also suggest that the production and preservation of samplers was not common until the end of the 15th century. The reason for this could be that it was only with the displacement of women from commercial life, the abolition of many monasteries during the Reformation, and the spread of the new image of women as heads of large households[26] that it made sense to keep "notebooks" in these households, which remained there and served as examples for the future, especially since the prices for printed pattern books must have been relatively high in relation to income.[27] The presence of letters on these samplers could be an indication of this thesis, because it was necessary for private households to mark their precious laundry so that it could be identified on the bleaching field. Ulrike Zischka emphasizes that "die ostfriesische Bezeichnung „Letterntuch“ für das Stickmustertuch […] schon sprachlich die Wichtigkeit der aufgestickten Lettern, der Buchstaben [verdeutlichte]."[28]

Fig. 3: Linen embroidered with multicolored silk in darning stitch and running stitch, 15th century.- https://data.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/id/

object/110901

object/110901

Fig. 4: Cross-stitch Sampler, 1st half of the 16th century. -https://web.archive.org/web/20110109204453/

http://www.vam.ac.uk/images/image/53364-popup.html

http://www.vam.ac.uk/images/image/53364-popup.html

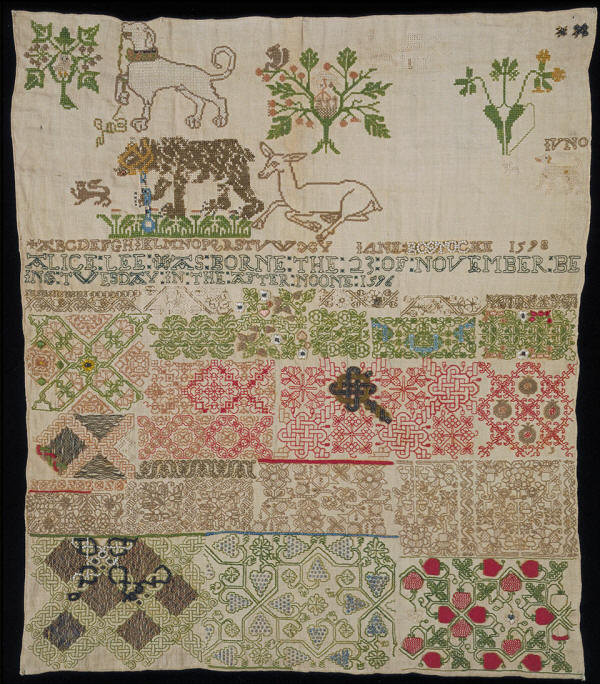

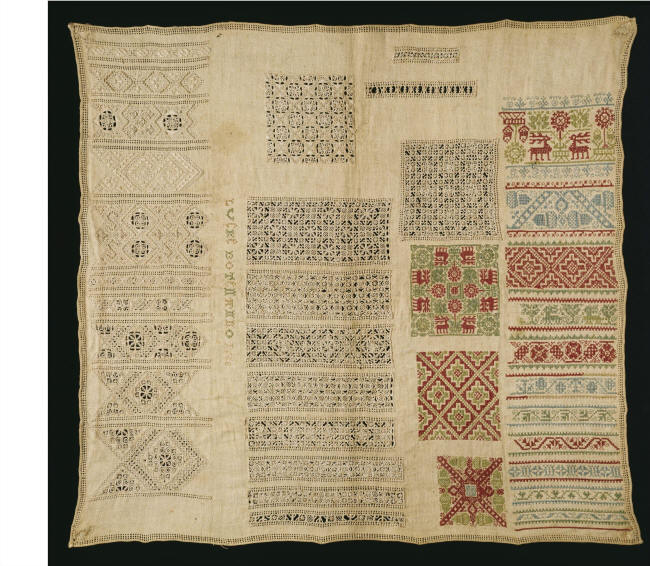

The most famous sampler of the 16th century is Jane Bostocke's sampler, created in 1598. It shares its rectangular shape, floral and animal motifs, alphabet, and a number of decorative patterns with earlier samplers that have been preserved. The metal threads, silk yarns, and beads used for embroidery, as well as the variety of embroidery stitches[29], were also found on earlier samplers. What is new, however, is that this sampler bears the name of the embroiderer and is dated, and an inscription indicates the purpose of the embroidery, namely to commemorate the birth of a child, Alice Lee, on November 23, 1596[30]. The Victoria & Albert Museum, which owns the sampler, describes the quality of the embroidery as very high, so it can be assumed that Jane Bostocke, who was a distant cousin of Alice Lee, was employed as an embroiderer in the child's household.[31] Another new feature is that the decorative patterns are no longer arranged randomly, but neatly in rows on the fabric background, while the floral and animal motifs still follow the random arrangement. The combination of elements from previous samplers with their random arrangement of motifs and the new elements described above means that this sampler is attributed to the "period of transition in the practical use of such items"[32], namely the transition "between a reference piece and a demonstration of its maker's skill"[33]. The same applies to an almost square sampler from Germany, which also shows patterns for linen embroidery arranged in rows. It was made by Lucke Boten in 1618.[34] The Cooper-Hewitt Collection of the Smithsonian Museum contains a sampler marked "Elizabeth Hine's work ended 1610." In contrast to the two samplers mentioned above, it has no blank areas on the base fabric, but is completely filled with depictions of animals, plants, buildings, ships, and people, with the image elements arranged in such a way that the overall picture is well suited to demonstrating the embroiderer's skills.[35] The picture suggests that the embroiderer was an adult.

Fig. 5: Sampler by Jane Bostocke, 1598. The sampler uses cross stitch, zigzag stitch, backstitch, satin stitch, chain stitch, buttonhole stitch, and French knots.

- https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O46183/sampler-jane-bostocke/

- https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O46183/sampler-jane-bostocke/

Fig. 6: Sampler by Lucke Boten, 1618. The sampler uses double backstitch, Montenegrin cross stitch, Italian cross stitch, satin stitch, and Richelieu embroidery.-

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O70238/sampler-boten-lucke/

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O70238/sampler-boten-lucke/

Fig. 7: Sampler by Elizabeth Hine, 1610. The sampler uses various counted stitches.- https://collection.cooperhewitt.org/objects/18697401/

The development of samplers or pattern cloths in England and Germany was basically the same in both countries. However, there are differences in the details, as can be seen from the samplers or pattern cloths that museums make available online[36]. This will be included and explained in the following.