English Samplers

The earliest indicators of the change in the purpose of samplers around 1600, from a collection of patterns and stitches to an integral part of education, are considered to be the dating and signing of samplers[1], whose purpose is said to have been to document a child's progress in the process of growing up[2], which cannot apply to the Bostocke sampler if we assume that Jane Bostocke was a professional embroiderer. The addition of alphabets around the middle of the 17th century is seen as a supporting argument[3], although it should be noted that the German sampler from the first half of the 16th century and the Jane Bostocke sampler already feature an alphabet. However, the clearly ordered and planned arrangement of decorative patterns in separate rows, while retaining the previous variety of embroidery stitches and motifs,[4] mostly in addition to pictorial patterns that were still arranged in the style of spot samplers, can be seen as a significant change towards a new form – long and narrow. This made it easier to store a sampler rolled up in a needlework basket without damaging the patterns.[5] The width of the samplers was determined by the width of the linen,[6] while the length could be chosen freely. The area for embroidery was now used in its entirety[7]. Samplers now looked like a long band[8] – hence the name "band sampler."

Fig. 1: Spot sampler, England, first half of the 17th century. The sampler uses slant stitch, half cross stitch, chain stitch, running stitch, staggered tapestry stitch, and others.- https://collection.cooperhewitt.org/objects/18616917/

Fig. 2: Band sampler, Germany, 17th century. The sampler uses cross stitch, eyelet stitch, and double running stitch.- https://collection.cooperhewitt.org/objects/18616809/

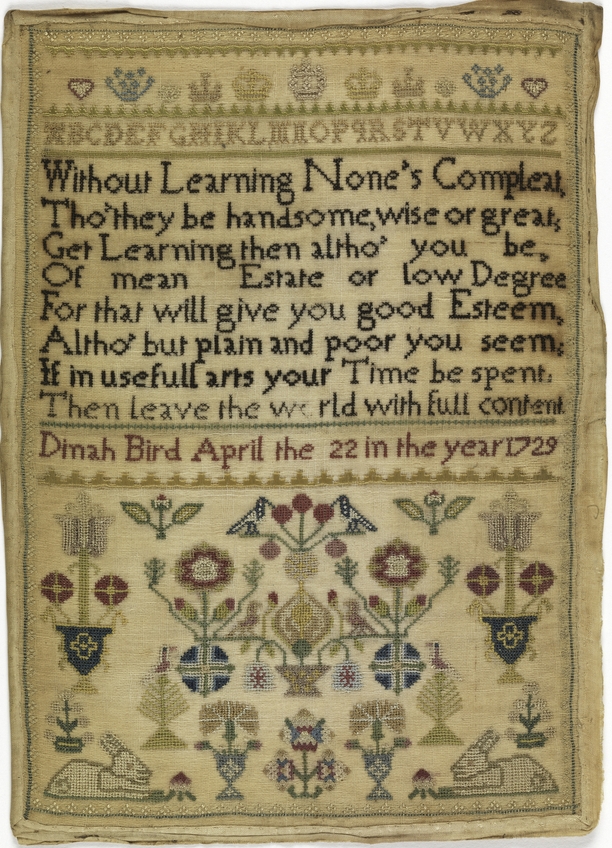

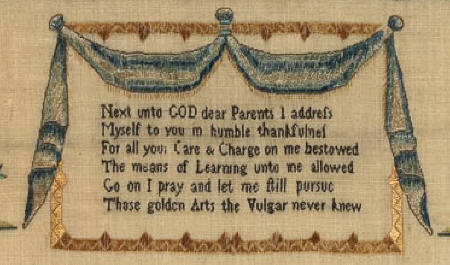

The form and planned arrangement of the motifs give these samplers a rather formalized appearance, suggesting that there was indeed an underlying educational concept that emphasized discipline, order, and thriftiness and sought to prevent idleness.[9] Definitive confirmation that the production of samplers played a role in the education of girls comes from the fact that samplers were increasingly marked with the name or initials of the embroiderer, her age, and the date of production. For example, there is a sampler from 1644 that was made by 10-year-old Frances Bridon.[10] It is common practice in England to label samplers with the full name of the embroiderer; initials are rarely used instead of the full name, which may indicate that embroidery skills were particularly socially recognized and proudly displayed. The frequently used inscription "... is my name and with my hand I made the same"[11] or "... with my needle I wrought the same"[12] seems to illustrate this. Inscriptions indicating the age of the embroiderer show that the samplers were made by children or young people.[13] The children are mostly between seven and thirteen years old. Despite their modesty, their pride in their achievements is evident in the frequently occurring inscription "I am a maid but young, my skill is yet but small, I hope that God will bless me so that I shall live to mend this all."[14] Some of these samplers contain sayings that mention the name of the teacher[15] or use her initials. The latter suggests that certain teachers were very well known and that the fact that a girl had been their pupil was a recommendation for a future employer. The position of a needlework teacher was obviously desirable because of the greater independence and autonomy it offered, as can be seen from the statement that Elizabeth Hopkins embroidered somewhat rebelliously in her sampler in 1711: "When I was young I little thought that wit must be so dearly bought, But now experience tells me how if I would thrive that I must bow and bend unto another's will that I might learn both art and skill to get my living with my hands so that I might be free from bonds that mine own Dame then I might be and freed from all such slavery."[16] Several samplers from the 17th and 18th centuries also emphasize the value of schools[17] and learning itself, which is more important than owning a house and land[18], which is why the inscriptions occasionally thank parents or a patron for the opportunity to learn.[19]

Fig. 3: Sampler with praise for learning, 1729. The sampler uses cross stitch, satin stitch, rococo stitch, running stitch, and double running stitch.- https://collection.cooperhewitt.org/objects/18617181/

Fig. 4: Detail from the sampler by Sarah Williamson, 1795

The gratitude expressed to her parents for their care and the opportunity to learn, both in the choice of words and the design of the sampler suggest that Sarah Williamson came from a wealthy family.-

https://data.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/id/object/110940

The gratitude expressed to her parents for their care and the opportunity to learn, both in the choice of words and the design of the sampler suggest that Sarah Williamson came from a wealthy family.-

https://data.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/id/object/110940

Fig. 5: Excerpt from the sampler by Mary Culley from Finchamstead, 1790. At the bottom of the sampler is the inscription:

"Thanks to Mr. Saint John for giving me schooling and I hope to return it by improving God save the church our king." It is possible that the aforementioned Mr. Saint John financed a local school or enabled his tenants' children to attend school.-

https://data.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/id/object/110713

"Thanks to Mr. Saint John for giving me schooling and I hope to return it by improving God save the church our king." It is possible that the aforementioned Mr. Saint John financed a local school or enabled his tenants' children to attend school.-

https://data.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/id/object/110713

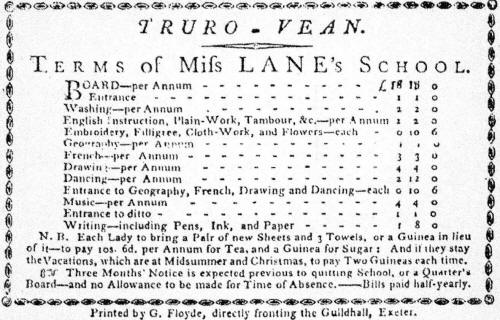

The findings from the samplers show that needlework lessons were generally part of the education and upbringing of girls. Contrary to the demands of the Reformation and especially the Puritans to establish schools for boys and girls and, in particular, to improve the situation of the poor through schooling, little changed in the existing system of home schooling and class-based education.[20] Apart from social status, access to education was also gender-dependent, as the education of women was seen as a threat to male dominance in society.[21] This did not change the fact that schooling for girls was permitted and even encouraged when it seemed useful for maintaining the social structure or when parents wanted and were able to provide their daughters with an education.[22] For example, there were girls who learned Latin,[23] which had been important since the Middle Ages, especially for merchants, because Latin was the lingua franca of the time and international business was conducted in Latin until the mid-17th century, when French became the new lingua franca due to the new leadership role of France under Louis XIV. At the beginning of the 17th century, there were grammar schools for girls that followed the same classical curriculum as those for boys. These were supplemented in the mid-17th century by private schools that taught mathematics, writing, and modern languages. It is possible that needlework was also taught in these schools to make the education appear acceptable to the outside world.[24] For the daughters of wealthy families of the nobility and gentry, there were so-called finishing schools from 1617 onwards, where needlework, conversation, manners, dancing, and music were taught.[25] They were intended for older girls who were about to enter society. All these opportunities were reserved for daughters of wealthy families, as annual fees had to be paid for schooling.[26]

Fig. 6: School costs, broken down by subject.- In: Rebecca Scott, Samplers, Oxford 2009, p. 56

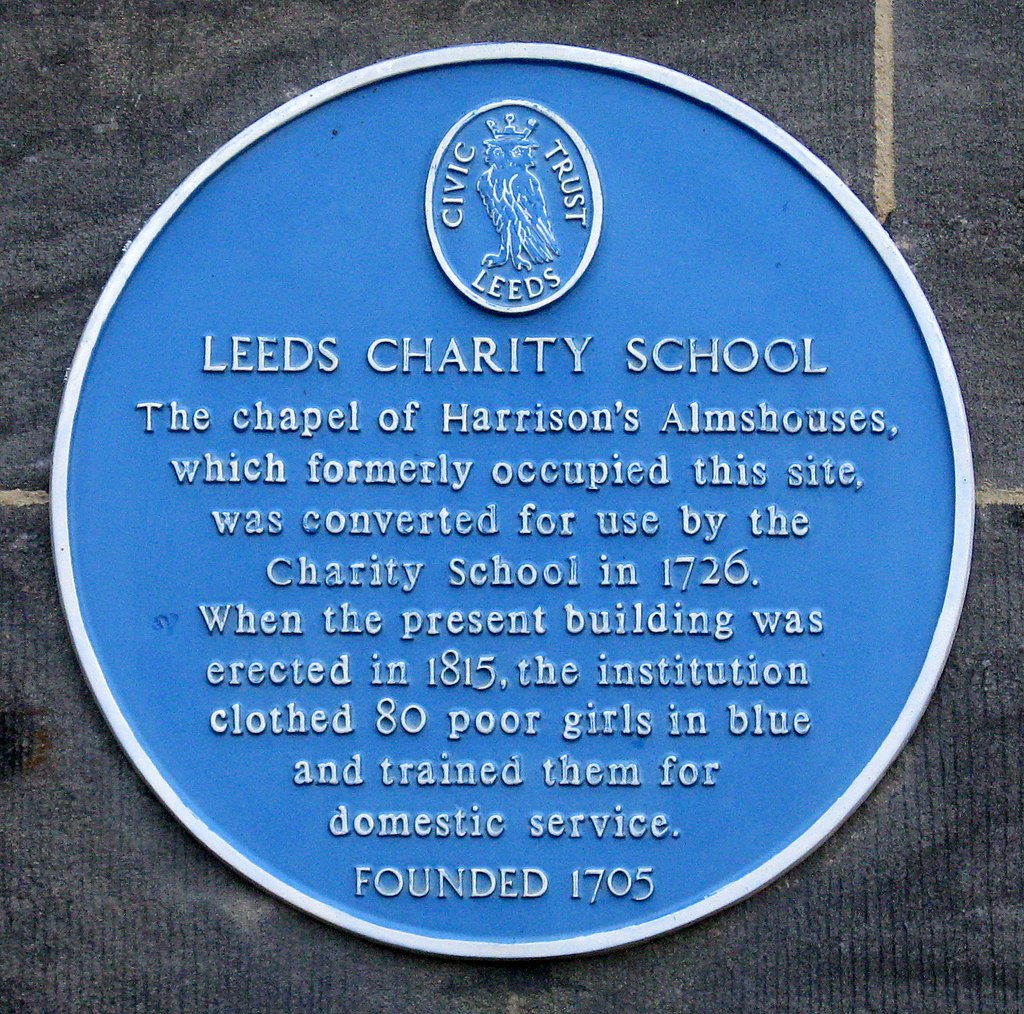

In addition, since the 16th century there had been so-called charity schools,[27] which were financed in rural areas by wealthy landowners in a parish and in cities by committees that carried out fundraising activities to attract donors who made regular contributions to the school's upkeep. In some cases, such charity schools and orphanages were financed, at least in part, by the sale of linen and clothing or services such as embroidery and sewing, which were produced or provided by the inmates.[28] The charity school movement was based on several factors: on the one hand, the Puritan belief in the value of education and upbringing for everyone, and on the other hand, the effort to prevent unrest caused by the growing number of poor people in the cities, which was the result of population growth and increasing urbanization due to the significant rise in agricultural productivity and the demand for goods and handicrafts. Thus, in 1699, the Society for the Propagation of Christian Knowledge was founded, which sought in particular to promote religious education in order to prevent moral decline and a slide into crime.[29]

Fig. 7: Commemorative plaque on the building of the former Leeds Charity School.- https://www.childrenshomes.org.uk/LeedsCharity/

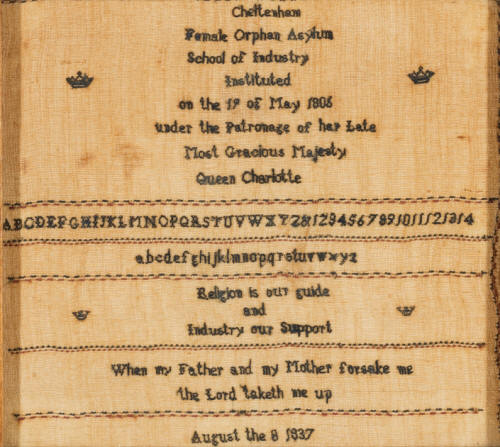

Fig. 8: Sampler commemorating the founding of the orphanage in Cheltenham, August 8, 1837.- https://collection.cooperhewitt.org/objects/18727651/

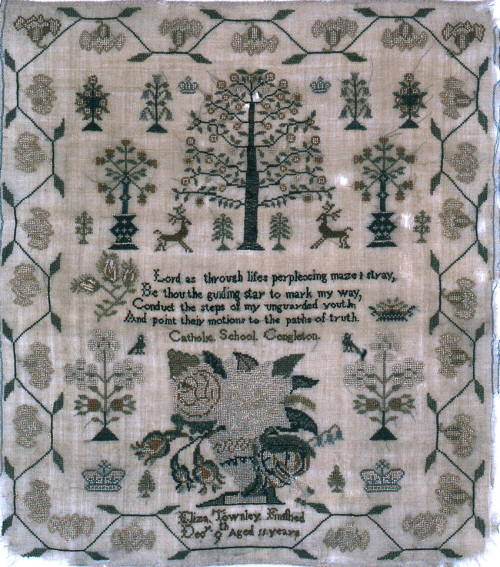

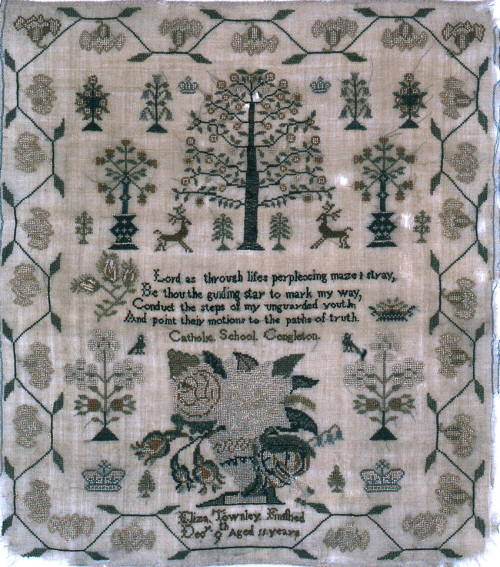

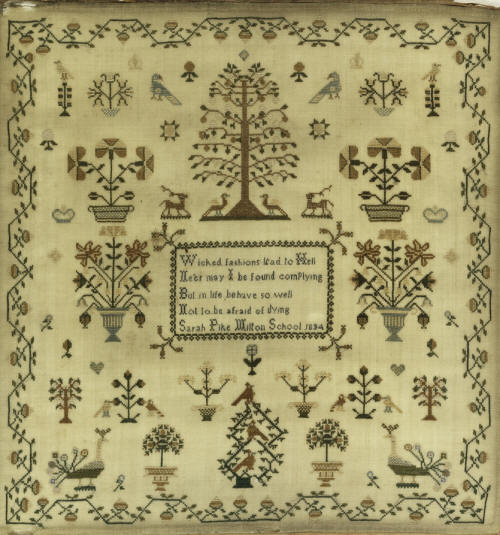

The education and upbringing of daughters from wealthy families, as well as that of daughters from poor families, followed the principle of preparing girls for their socially prescribed roles as adults. For the daughters of wealthy families, this meant preparing them for the role of wife to a landowner, who had to be able to represent her husband in society and perform the extensive tasks of instructing and supervising numerous servants on a country estate and alleviating the hardships of tenants and the poor. This objective remained unchanged for centuries: Bowden cites the example of Lady Frances Hobart (1603-1664), who played an instrument, sang, danced, could read, write, and do arithmetic, did needlework, and ran the household.[30] Almost 200 years later, the skills that Jane Austen lists in her novel „Pride and Prejudice“ (1813) as requirements for the wife of a landowner correspond to those mastered by Lady Hobart[31]. Jane Austen's novel also makes it clear that such an education was sought after by ambitious families who had acquired their wealth through trade or craftsmanship in order to achieve social advancement, which was often ridiculed in public, as a caricature from 1809 shows[32]. Accordingly, a sampler from 1835 reads: "Go on dear Elizabeth strive to excel In book and work and needle well For book and work they both intend To make a housewife and a friend."[33] While the daughters of the nobility and gentry practiced embroidery as a leisure activity or as a demonstration of the fact that they did not have to work, for the poor population it was a matter of acquiring skills that would make them suitable for service in wealthy households or enable them to earn a living as seamstresses or embroiderer[34] or even to rise to the rank of teacher or companion[35]. Embroidery therefore always had its uses. As a sampler from 1790 states: "Two things, the needle and the book we find, Help to accomplish all the female kind. The shining needle draws the fine spun thread, covering the person and adorning the head. Since neatness gives the charms that all commend, the needle is the female's choiest friend."[36] And in 1808 it says: "Of female arts in usefulness, the needle far excels the rest."[37] Regardless of whether a woman ran a large household or worked as a servant, she was expected to remain in the background and submit to male authority, to be modest and concentrate on her destiny, as Elizabeth Davey noted on her sampler in 1721: "A Prudent Woman all her time imploys that tends to wisdom not in talk & toys"[38] . In 1817, eight-year-old Ann Wood described the attitude that girls were taught with "With cheerful mind we yield to men The higher Honors of the Pen The Needles our great care In this we chiefly wish to shine How far the arts already mine This sampler does declare," and in 1830, Jane Bailey recommended on her sampler: "Seek to be good but aim not to be great, A woman's noble station is retreat, Her fairest virtues fly from public sight, Domestic worth still shuns too strong a light."[39] Unfortunately, it is not possible to determine from the samplers which social class the respective embroiderer belonged to. One might be tempted to infer social status from the type of materials used; however, most samplers are embroidered with silk thread and only a few with wool thread, so this correlation is rather unlikely. Some samplers, however, indicate the school where they were made, including various charity schools[40] and orphanages[41] .

Fig. 9: Sampler by Ann and Deborah Jones, 1787. The sampler was made at Ackworth School in Yorkshire, founded by Quakers in 1779. The school was a boarding school for girls and boys. The embroidery in medallion shapes is typical of Quaker embroidery.-

https://data.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/id/object/200917

https://data.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/id/object/200917

Fig. 10: Sampler by Eliza Townley, early 19th century. Eliza Townley was a pupil at the Catholic school in Congleton, Cheshire.-

https://collection.cooperhewitt.org/objects/18564401/

https://collection.cooperhewitt.org/objects/18564401/

Fig. 11: Sampler by Sarah Pike, 1834. Sarah Pike attended school in Milton, Cambridgeshire.-

https://collection.cooperhewitt.org/objects/18617239/

https://collection.cooperhewitt.org/objects/18617239/

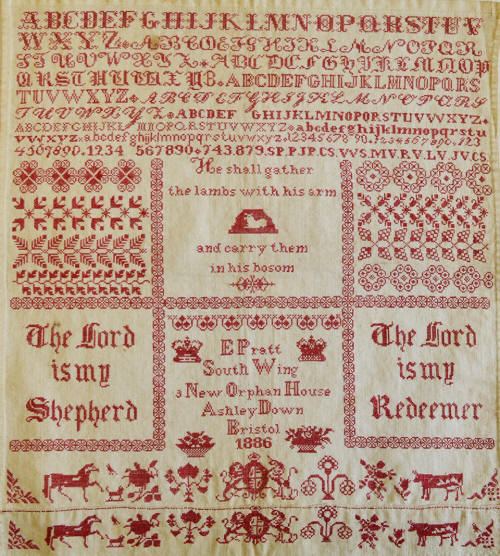

Fig. 12: Sampler by E. Pratt, 1886. E. Pratt lived in the south wing of the New Orphanage in Bristol, Ashley Down Rd. The orphanage was built between 1849 and 1870.- https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O1369605/sampler-e-pratt/

The curriculum of charity schools almost everywhere included reading, singing, and handicrafts, i.e., sewing, darning, knitting, and embroidery[42] ; depending on the preferences of the sponsors, lessons in writing and arithmetic were also given, and in general, the focus was on moral and religious instruction[43] . In accordance with Puritan/Calvinist beliefs, it was important to be as diligent as possible and avoid wasting time, with the aim of accustoming children to a structured and disciplined daily routine. This is explicitly addressed in a sampler from 1826: "If idly spent no art or care Time's blessing can restore, And God requires a strict amount For ev'ry mis-spent hour, Short is our longest day of life. And soon its prospect ends, Yet on that day's Uncertain date, Eternity depends."[44] Handicrafts, and in particular embroidery, which required concentration, played a special role in this, especially as it promoted patience, subordination, and obedience while also requiring long periods of sitting still[45] . The latter virtues were also expected of the daughters of the nobility and gentry, who were first under the guardianship of their fathers and then their husbands[46] . In this way, embroidery became established as a female activity for all social classes, although in wealthy circles it was already identified at the beginning of the 18th century with a lifestyle that declared embroidery to be a leisure activity[47] . In line with the behavioral goals of education, the vast majority of samplers from the early 17th century to almost the end of the 19th century feature religious and moral texts and sayings. These include the Ten Commandments[48] , the Lord's Prayer[49] , quotations from the Bible[50] and the Psalms[51] , as well as exhortations to live a life in fear of God and to be aware of the transience of earthly goods[52] . The exhortations to strive for virtues such as moderation, modesty, wisdom, sincerity, truthfulness, gratitude, obedience, and love for one's parents are too numerous to document in detail. A large number of samplers praise charity, whereby this praise can be understood both as an expression of gratitude and as an indication that the embroiderer's family supported charitable causes.

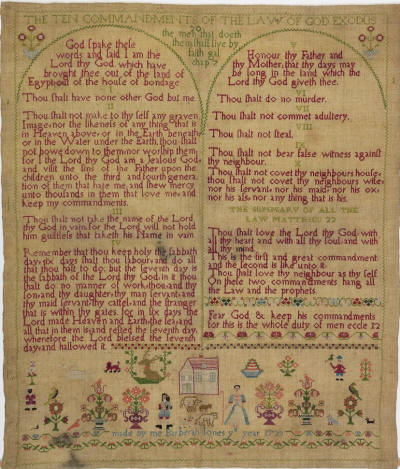

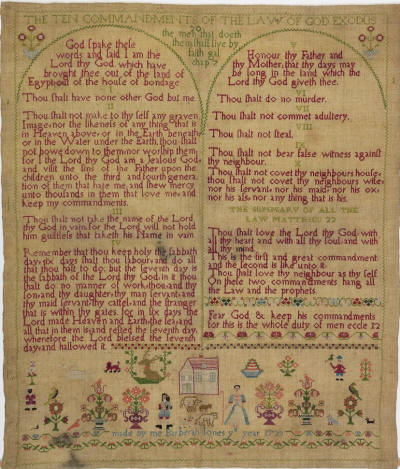

Fig. 13: Sampler by Barbara Jones, 1723. The sampler depicts the Ten Commandments.-

https://data.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/id/object/110671

https://data.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/id/object/110671

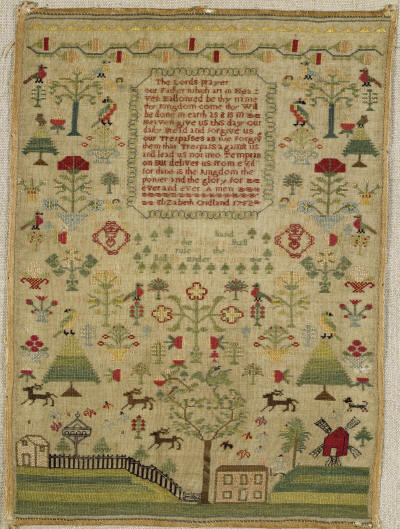

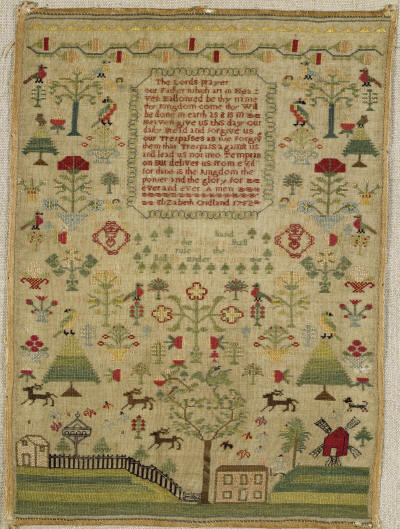

Fig. 14: Sampler by Elizabeth Cridland, 1752. The Lord's Prayer is embroidered on the sampler.-

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O70353/sampler-cridland-elizabeth/

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O70353/sampler-cridland-elizabeth/

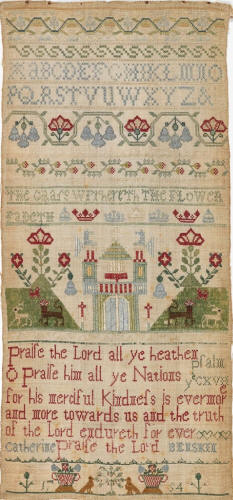

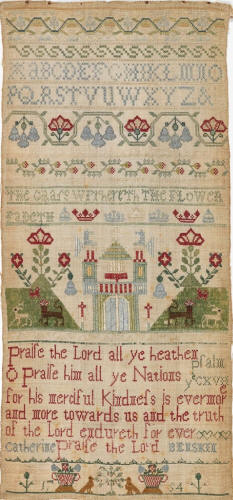

Fig. 15: Sampler by Catherine Benskin, 1754. A verse from Psalm 117 is embroidered on the sampler.-

https://data.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/id/object/110698

https://data.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/id/object/110698

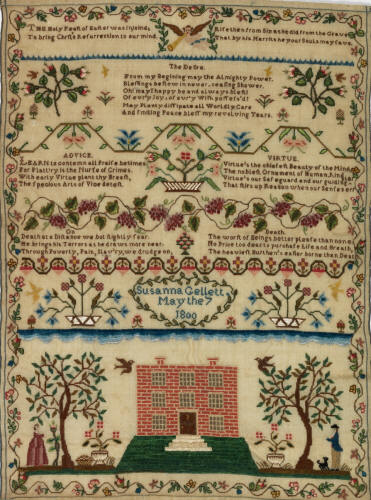

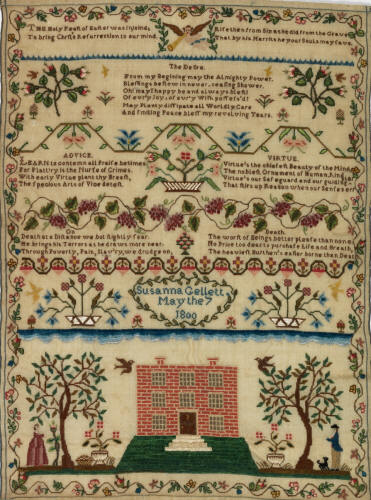

Fig. 16: Sampler by Susanna Gellett, 1800. The sampler reminds us of the transience of life and exhorts us to live a virtuous life.-

https://data.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/id/object/110782

https://data.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/id/object/110782

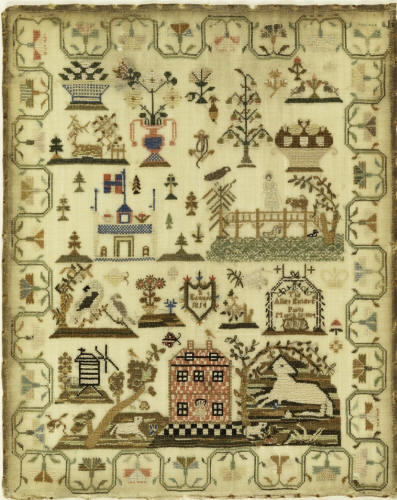

Since the 1720s, a gradual change has taken place in the form of samplers, with "picture formats" first appearing sporadically and then, from the middle of the century onwards, becoming more common, i.e., the long side is not significantly longer than the short side and vice versa. From 1750 onwards, these picture formats predominated, and ribbon samplers became rare. At the same time, the arrangement of motifs on samplers changed from rows to a more symmetrical image structure. These samplers were no longer made as practice pieces or pattern collections, but were intended to be hung up on display to demonstrate the education and skills of the daughter of the house[53] . Samplers now also reflect the genealogy of a family[54] , mourn the loss of loved ones[55] , praise the value of friendship[56] or capture a pictorial representation of their native surroundings[57] . Although the vast majority of samplers continued to contain alphabets, numbers and religious-moral sayings, motifs now also appeared that testified to the broad education of the embroiderers. In the last quarter of the 18th century, so-called map samplers appeared, demonstrating both geographical knowledge and embroidery skills.

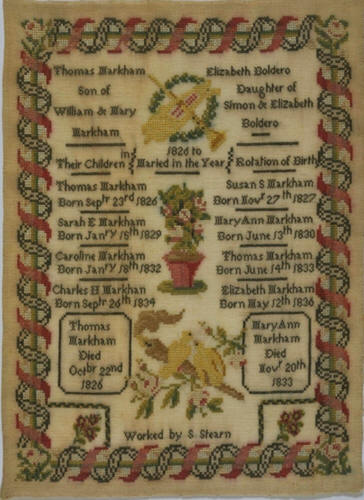

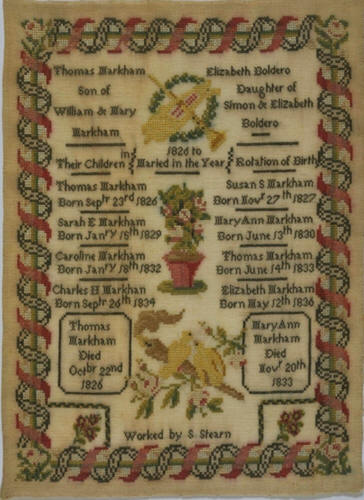

Fig. 17: Sampler by S. Stearn, ca. 1836-1840. S. Stearn notes the dates of birth and death of members of her family.

The musical instruments and birds depicted suggest that the Markham family was closely involved with music.-

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O70556/

sampler-stearn-s/

The musical instruments and birds depicted suggest that the Markham family was closely involved with music.-

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O70556/

sampler-stearn-s/

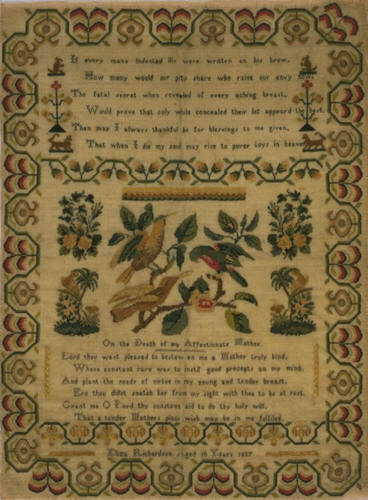

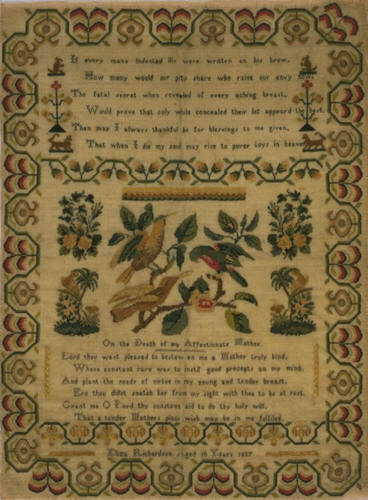

Fig. 18: Sampler by Eliza Richardson, 1837. Ten-year-old Eliza Richardson mourns her deceased mother with this sampler.-

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O70538/

sampler-richardson-eliza/

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O70538/

sampler-richardson-eliza/

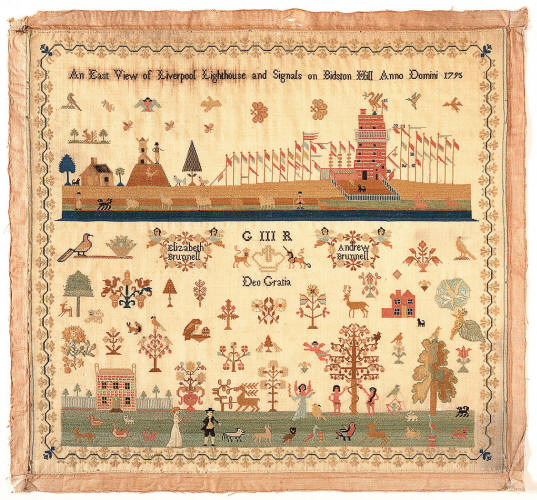

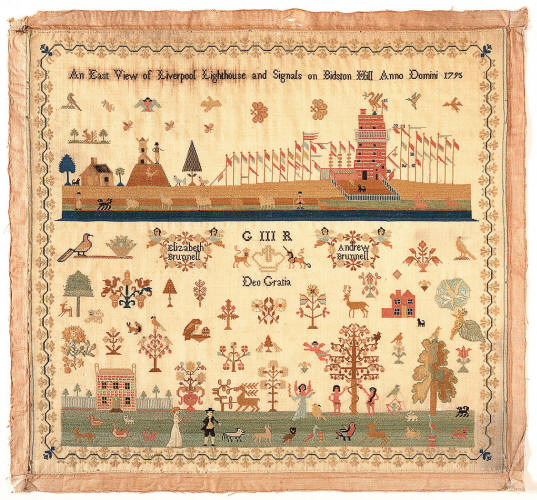

Fig. 19: The sampler was probably embroidered by Elizabeth Brunnell in 1795. It depicts a partial view of her hometown of Liverpool.- https://collection.cooperhewitt.org/

objects/18483231/

objects/18483231/

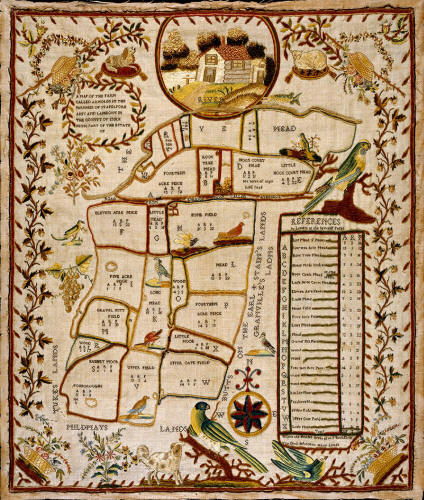

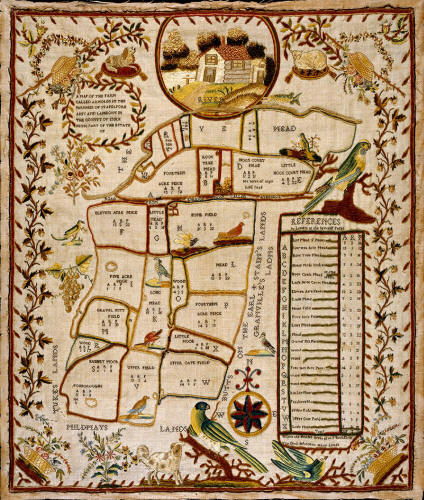

Fig. 20: Sampler entitled "A map of the farm called Arnolds in the Parishes of Stapleforb Abby and Lamboun in the County of Essex being part of the estate of," ca. 1790. The sampler shows the exact location of the individual fields belonging to the farm. The embroiderer may have been the daughter of the farm's tenant.-

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/

O355538/the-farm-called-arnolds-in-sampler/the-farm-called-arnolds-in-sampler-unknown/

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/

O355538/the-farm-called-arnolds-in-sampler/the-farm-called-arnolds-in-sampler-unknown/

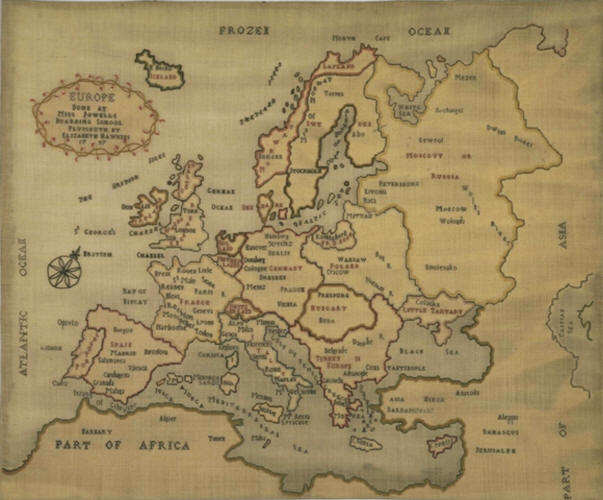

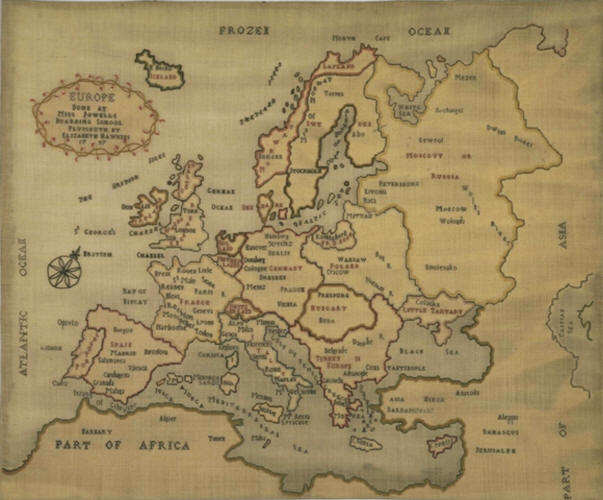

Fig. 21: Sampler by Elizabeth Hawkins, 1797. Elizabeth Hawkins was a student at Miss Powell's Boarding School in Plymouth, where she made this sampler.-

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O70394/

sampler-elizabeth-hawkins/

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O70394/

sampler-elizabeth-hawkins/

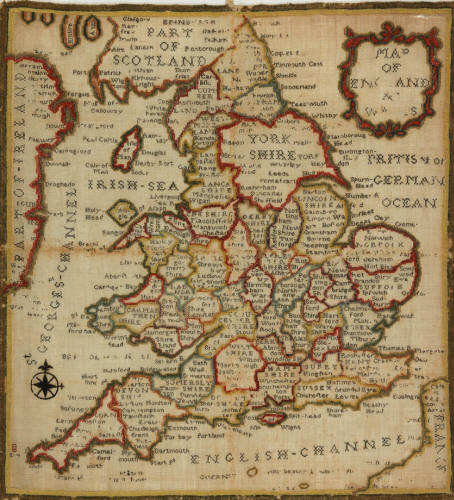

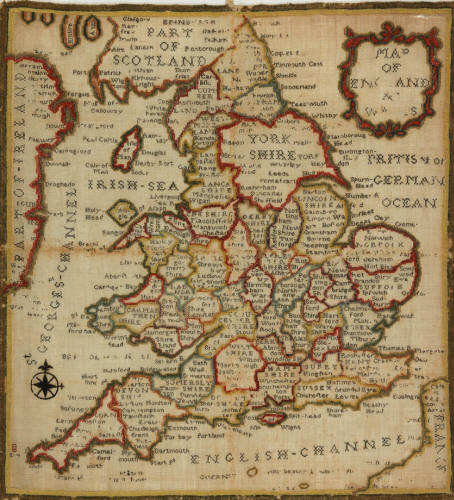

Fig. 22: Sampler by Ann Seaton, 1790

Ann Seaton lived in Lincoln, Lincolnshire. The sampler lists the counties and the larger towns in the counties.-

https://data.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/id/

object/110712

Ann Seaton lived in Lincoln, Lincolnshire. The sampler lists the counties and the larger towns in the counties.-

https://data.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/id/

object/110712

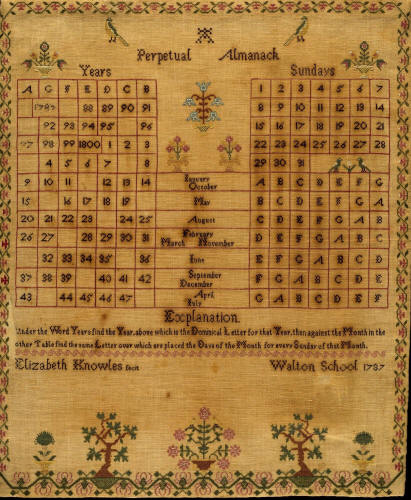

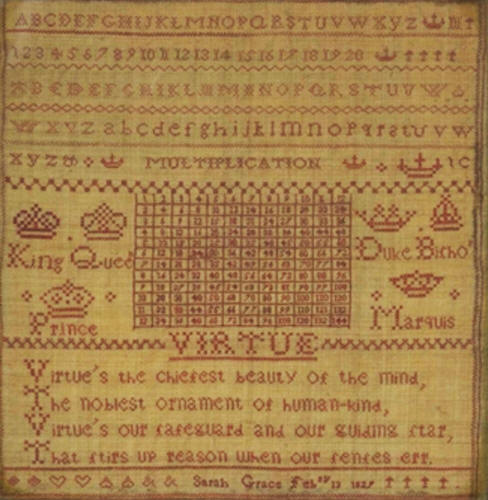

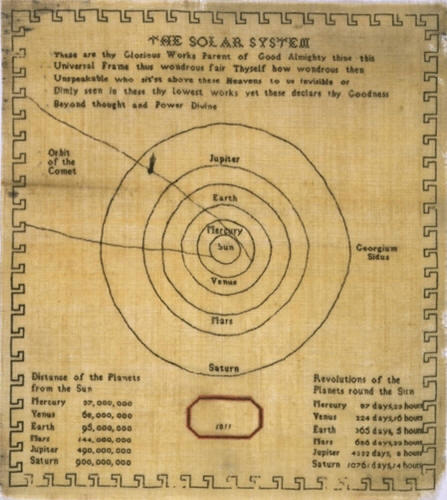

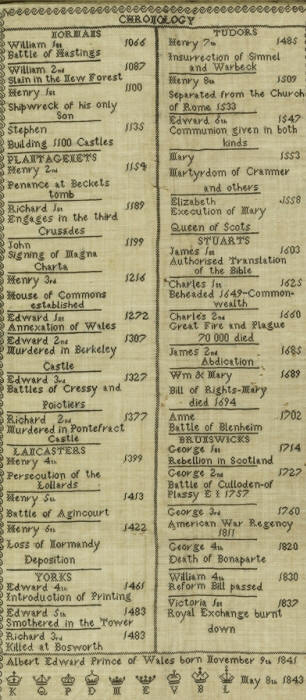

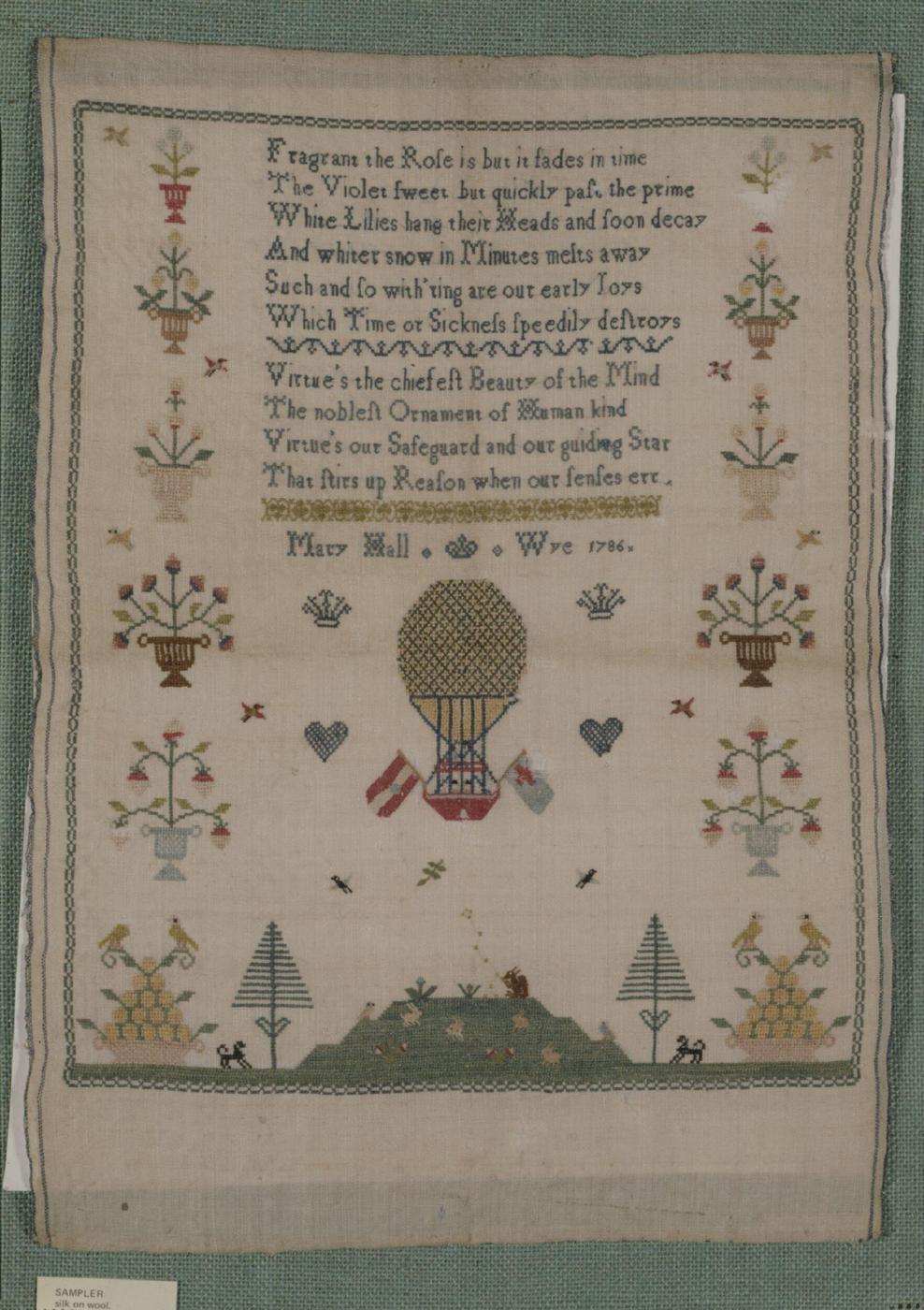

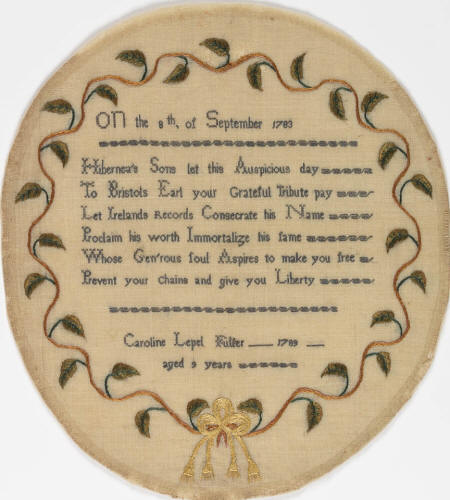

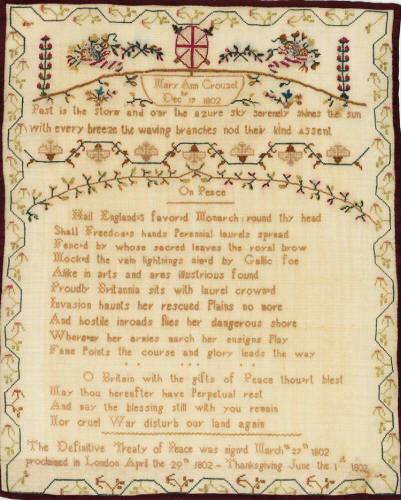

In 1787, Harriet Knowles, a pupil at Walton School, demonstrated her outstanding mathematical abilities with a Perpetual Almanack[58] , and a sampler from 1811 depicts the solar system[59] , while a sampler from 1827 contains a multiplication table[60] . In 1843, an embroiderer created a sampler that records important dates in English history in two long columns, beginning with the Battle of Hastings in 1066 and ending with the birth of Albert Edward, Prince of Wales, in 1841.[61] The fact that girls also took part in current events is shown by the depiction of a hot air balloon on a sampler from 1786[62] , a sampler from 1802 celebrating the Peace of Amiens,[63] and the decidedly political statement on Caroline Lepel Fuller's sampler from 1789, which praises the role of Frederick Hervey, 4th Earl of Bristol, in the enactment of the Renunciation Act of 1783[64] , and a sampler by S. Edwards commemorating the entry of the Allied forces into Paris on March 31, 1814.[65]

Fig. 23: Sampler by Elizabeth Knowles, 1787. Elizabeth Knowles created this perpetual calendar, which allows the dating of Sundays for the next 50 years. She added "instructions for use." She demonstrated her knowledge of Latin by using "fecit" instead of the usual "made." Elizabeth was a student at Walton School, whose location in England cannot be clearly determined.-

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O70381/

perpetual-almanack-sampler-knowles-elizabeth/

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O70381/

perpetual-almanack-sampler-knowles-elizabeth/

Fig. 24: Sampler by Sarah Grace, 1827. Sarah Grace adds the multiplication table to the elements of the sampler that were customary at the time, such as alphabets and numerals, crowns, and moral verses.- https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O70504/

sampler-sarah-grace/

sampler-sarah-grace/

Fig. 25: Sampler, 1811. This sampler combines a depiction of the solar system with praise for divine creation.-

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O70501/

the-solar-system-sampler-unknown/?carousel-image=2006AP0194

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O70501/

the-solar-system-sampler-unknown/?carousel-image=2006AP0194

Fig. 26: Sampler, 1843. The sampler lists important dates in English history, beginning with the Battle of Hastings in 1066 to the birth of Albert Edward, Prince of Wales, in 1841.-

https://collection.cooperhewitt.org/objects/

18727681/

https://collection.cooperhewitt.org/objects/

18727681/

Fig. 27: Sampler by Mary Hall, 1786. Mary Hall combines the depiction of the hot air balloon, which was successfully launched for the first time in 1783, with the traditional reminder of transience and the admonition to live a virtuous life.-

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O93419/

sampler-hall-mary/

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O93419/

sampler-hall-mary/

Fig. 28: Caroline Lepel Fuller's sampler, 1789. The sampler praises the role of Frederick Hervey, 4th Earl of Bristol, who

was active in the Irish independence movement and had introduced the

Renunciation Act of 1783.-

https://data.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/id/

object/110771

was active in the Irish independence movement and had introduced the

Renunciation Act of 1783.-

https://data.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/id/

object/110771

Fig. 29: Sampler by Mary Anne Crouzet, 1802. The sampler contains an eulogy to England under George III and celebrates the Peace of Amiens of 1802, which ended the Second Coalition War.-

https://data.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/id/object/110783

https://data.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/id/object/110783

Fig. 30: Sampler by S. Edwards, 1814. Quite hidden among the numerous pictorial elements of this sampler is a reference to the Allied invasion of Paris on March 31, 1814, which in turn led to Napoleon's abdication.-

https://collection.cooperhewitt.org/objects/18617191/

https://collection.cooperhewitt.org/objects/18617191/

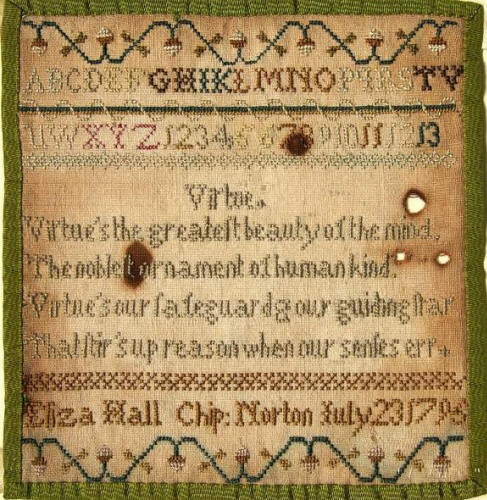

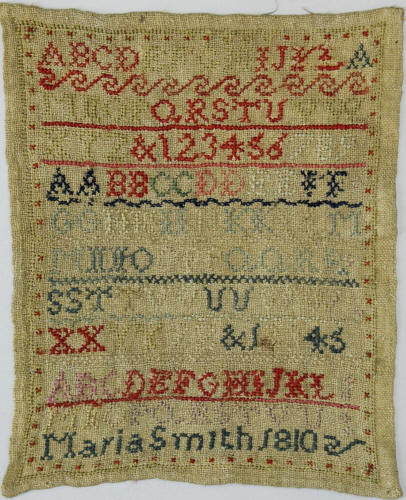

The aforementioned samplers were probably made by embroiderers from the upper and middle classes. One sampler, which depicts a map of Europe, is inscribed "done at Miss Powell's boarding school Plymouth"[66] . As mentioned above, tuition fees had to be paid for such a school, which was hardly possible for the lower middle class and the lower class, which had grown enormously as a result of the agricultural revolution and had moved to the cities in the course of industrialization, where they lived in extremely miserable conditions. For the latter, any form of education still depended on admission to charity schools or orphanages. The conditions under which daughters of lower-class families lived are vividly illustrated by the sampler created around 1830 by Elizabeth Parker, who, as a servant in a noble household, had to endure mistreatment and abuse that brought her close to suicide[67] . Her sampler also sheds light on the education she and many girls from the lower classes received: she cannot write, but she can embroider the words[68] , which in turn underlines the importance of embroidery and needlework in general for the education of maids. Since the end of the 18th century, the proportion of samplers limited to alphabets, numbers, and names with dates has increased, and these were often made on and with coarse materials—in particular, the color scheme was limited to one or two colors. It can be assumed that with the increase in the number of girls from the lower classes, their training in embroidery was limited to the bare essentials, and the embroidery of more complicated patterns with more valuable materials was left to the ladies of the upper classes and the gentry.

Fig. 31: Sampler by Eliza Hall from Chipping Norton, Oxfordshire, 1795. This sampler is still embroidered with silk thread.-

https://data.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/id/object/110775

https://data.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/id/object/110775

Fig. 32: Sampler by Mary Smith, 1810. This sampler is embroidered with the less expensive wool.-

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O355587/sampler/sampler-smith-maria/

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O355587/sampler/sampler-smith-maria/

When considering samplers and their history, the use of stitch types and their development is of particular importance. English samplers from the 17th century use a variety of different stitches, such as backstitch, running stitch, satin stitch, chain stitch, ladder stitch, buttonhole stitch, braid stitch, stem stitch, and cross stitch. Many of these stitches were used to embellish clothing, e.g., collars, cuffs, waistcoats, etc. This changed at the beginning of the 18th century: in 1723, Barbara Jones made a sampler entirely in cross stitch[69] , then in 1729 Mary Smith[70] and in 1735 an unknown embroiderer embroidered a sampler entirely in cross stitch[71] . From the middle of the 18th century onwards, cross-stitch was predominantly used on samplers and the proportion of other stitches – often half cross-stitch or tapestry stitch – decreased more and more until, from the 1820s onwards, samplers were made exclusively in cross-stitch, with very few exceptions. There is consensus in the literature that from this period onwards, "the word 'sampler' has generally come to be equated with 'cross stitch'"[72] . One reason for this change may be that, from the 17th century onwards, embroidery was increasingly used for items of domestic or everyday use, such as chair covers, book covers, mirror backs, boxes, and much more.[73] In this regard, cross stitch offered the advantage of reinforcing the embroidery base, especially when the crosses were worked individually. This made the embroidered items more durable.[74] On the other hand, as described above, since the 16th century, girls and women from all walks of life who were not professionally trained increasingly took up embroidery, and they may have preferred cross stitch because it is easy to embroider. The stitches of a pattern could be easily counted on linen fabric, and one only had to pay attention to the direction in which the crosses were embroidered, although occasionally the crosses did not follow one direction throughout. In addition, cross-stitch is easy to unpick, so mistakes can be easily corrected.

In the second half of the 19th century, the number of samplers decreased significantly, which may have been due to a change in fashion on the one hand and social change on the other. For the 20th century, Rebecca Scott points out that the First World War led to far fewer servants being employed, which in turn meant that there was no longer a need for the working class to master needlework, especially as technological progress also made many types of needlework redundant. Interest in handicrafts also declined among the wealthy aristocracy and gentry, as there were now sufficient new opportunities for entertainment and leisure activities. [75]

In the second half of the 19th century, the number of samplers decreased significantly, which may have been due to a change in fashion on the one hand and social change on the other. For the 20th century, Rebecca Scott points out that the First World War led to far fewer servants being employed, which in turn meant that there was no longer a need for the working class to master needlework, especially as technological progress also made many types of needlework redundant. Interest in handicrafts also declined among the wealthy aristocracy and gentry, as there were now sufficient new opportunities for entertainment and leisure activities. [75]