Embroidery Producers and Their Organization in the Middle Ages

"Die Tätigkeit des Stickens wurde im Mittelalter und der frühen Neuzeit […] als von Beginn der Menschheit an genuin weibliches Sujet betrachtet, […]denn bis ins Hochmittelalter rechnete man das Sticken wie allgemein die Herstellung von Textilien, die zunächst vor allem für den Eigenbedarf produziert wurden, grundsätzlich zur Frauenarbeit."[1] writes Christiane Bergemann, while Ruth Grönwoldt limits the view that only women produced embroidery to "nicht professionelle[r] Stickerei"[2] . In contrast, Katrin Kania believes that "wenn sich auf der Mehrzahl der Bilder Frauen bei textilen Tätigkeiten und Männer meist in anderen Tätigkeiten finden lassen, […] dies nicht zwingend bedeuten [muss], dass Textilherstellung im Mittelalter gemeinhin als Frauensache betrachtet wurde."[3]

So what is the division of roles between women and men in the production of embroidery? Did it change over the course of five centuries? If so, what factors led to a change in the division of roles?

Valentina S. Grub sees Bergemann's view as a stereotype that was created "erroneously, if romantically, by Victorian medievalists"[4] . Alexandra Gajewskia/Stefanie Seeberg also believe that this stereotype needs to be examined more closely and that a distinction must be made between women from different social classes[5] . They note that noblewomen were producers, donors, patrons, and consumers of textile art[6] . Heidrich limits the restriction of textile work to women to the early Middle Ages, noting that women specialized in individual tasks. She refers to land registers, documents, and other written sources from the early Middle Ages[7] .

With regard to the early Middle Ages, Heidrich's opinion seems to be confirmed by . As mentioned above, the embroidery on Bathilde's robe, which dates from around 680, was probably commissioned by Bathilde herself and made by English women whom she gathered at her court[8] . The so-called "Maaseik Embroideries" presented above are also said to be attributable to women known by name, namely Saint Relindis (+ 750), a daughter of the Frankish count Adelard. After the death of her sister Harlindis in 745, who was the first abbess of the monastery founded by their father, Relindis succeeded her as abbess. According to the Vita, written between 855 and 881, Relindis is said to have produced the embroideries, while more recent research places their origin in the 9th century.[9] The inscription on a maniple belonging to the donations also proves that Queen Ethelfleda (+ around 870, +918) commissioned embroidered textiles as a gift for Bishop Friedestan of Winchester.[10] There is also evidence of the production of a hunger cloth by Richlin, sister of Abbot Hartmut of St. Gallen, before 883.[11] The so-called war banner of Gerberga was also mentioned above, whose inscription "Gerberga me fecit" clearly identifies the embroiderer and makes it clear that it was important to her to identify herself as the donor and also the producer. As the sister of Emperor Otto I and Queen of Lotharingia, she created an embroidery with a political message that authenticates the real contemporary event on the one hand and, at the same time, exaggerates it by depicting Christ as the victor, thus taking the wind out of the sails of potential opponents.[12]

All of the embroidered textiles mentioned here were commissioned by noblewomen and/or made by them themselves. Three have a clearly sacred use, while Bathilde's shirt and Gerberga's war banner can also be interpreted as political messages. The depiction of the conquest of England on the Bayeux Tapestry can also be placed in this context. Both Bathilde and Gerberga use the medium of embroidery to assert their influence and demonstrate their personal and political position.

Women are also associated with embroidery in the High Middle Ages, either as patrons or as producers. It is said that Edith, the wife of Edward the Confessor (king of England from 1042 to 1066), embroidered her husband's coronation mantle. Margaret, wife of Scottish King Malcolm III (reigned 1058-1093), is also mentioned in written sources at as an embroiderer of liturgical vestments.[13] It is also recorded that Adelheid von Gammertingen donated two Lenten veils, which she had made herself, to Zwiefalten Abbey in the first half of the 12th century. [14]. Between 1272 and 1294, the so-called Clare Chasuble was created, named after Margaret de Clare, Duchess of Cornwall.[15] Gertrude, daughter of (Saint) Elizabeth of Thuringia, had two altar cloths made for the Altenberg a.d. Lahn monastery. She lived in this monastery from 1229 to 1297.[16] After becoming abbess in 1248, she endeavored to glorify her mother's life, commissioning an embroidery depicting scenes from her mother's life.[17]

There is also ample evidence of embroidery being produced in convents, although the names of the nuns who did the embroidery were generally not mentioned. However, as in the case of Heiningen Abbey, the names of the abbey's founders were recorded, which may be attributed to the influence of the visitors who belonged to the Cistercian Order, which was based on simplicity and asceticism.[18] The embroideries were not to bear the names of the nuns who had made them, because such works of art were not intended to serve the personal glory of the embroiderers, but exclusively the glory of God[19]. In 1240, for example, a visitation took place at the Lüne monastery, during which the nuns were expressly recommended to engage in textile work[20] , especially since it was believed that manual labor in the religious community provided people with a harmonious balance between mental and physical activity.[21] What Böse describes for late medieval monastic communities, namely that the " Herstellungsprozeß […] den Alltag der Schwestern in Stunden der Arbeit, des Gebets und der Unterweisung [strukturierte und] das dem Schreiben von Büchern vergleichbare Sticken und Wirken […] die Themen vor[gab], mit denen sich die Nonnen über Monate hinweg intensiv beschäftigen"[22], certainly also applies to the High Middle Ages from the visitors' point of view, especially since the reforms of the 11th century.

The women of the early Middle Ages who were known as embroiderers and patrons came from the nobility, at least in Germany. This also applies to the embroidering nuns, as nunneries were usually founded not only for religious reasons, but also to provide for unmarried daughters of the nobility. Not every woman could enter a convent in the Middle Ages; a person who wanted to enter a convent had to bring a dowry consisting of either a considerable sum of money or its equivalent in land or other valuables. For the Lower Saxon convents of Heiningen and Dorstadt, for example, this meant that the canonesses came from "zunächst exklusiv aus adligen und ministerialischen Familien, seit dem 14. Jahrhundert dann primär aus dem Braunschweiger Bürgertum, in protestantischer Zeit aus Adels- und Beamtenfamilien des Wolfenbütteler Umlandes und nach 1643 aus der katholischen Beamtenschaft des Hildesheimer"[23].

There is much to suggest that noblewomen were generally involved in embroidery not only in the early Middle Ages, but also beyond. Bumke explains that the content and objectives set out by Vincent of Beauvais in his work "De eruditione filiorum nobilium," written between 1247 and 1249, served as guidelines for the education of noble girls in the Middle Ages. Girls were to be kept constantly busy; idleness was to be avoided at all costs so that they would have no time for sinful thoughts. In addition to reading, writing, Latin, moral instruction, and learning rules of decorum and etiquette[24] , "sollten [sie] spinnen und weben, nähen und sticken lernen, und viele werden einen großen Teil ihres Lebens mit solchen Tätigkeiten zugebracht haben, auch wenn sie nicht von der Arbeit ihrer Hände leben mußten"[25] . Of the handicrafts mentioned, embroidery in particular was a non-essential activity—spinning, weaving, and sewing also had to be practiced as part of the peasant economy—that required leisure time. It is therefore understandable when Bergemann says that "das Sticken [habe sich] zum Statussymbol in der mittelalterlichen Gesellschaft [entwickelt."[26]

Presumably, the noble ladies embroidered textiles that were donated to a church for the needs of their own households. These were likely wall hangings that alleviated the cold of unheated rooms, as well as bed curtains, pillows, and similar items.[27] Clothing was probably also embroidered, as clothing had "eine weit größere Bedeutung für die äußerlichen Zeichen von Reichtum, Macht und gesellschaftlicher Stellung"[28] . According to the ordo doctrine that shaped the medieval worldview, each individual had to be assigned to one of the three estates, each of which had specific tasks. In his verse novel "Iwein," written around 1200, Hartmann von Aue describes Iwein's loss of identity when he tears the clothes from his body and lives in the forest like a savage. Only when he puts on clothing befitting his status does he regain confidence in his identity and is able to move in courtly circles again. Here, clothing represents not only the social classification of the individual, but also the attitudes and values of the person wearing it[29] . For others from the outside, clothing is a "zuverlässiger Indikator im komplexen Zeichensystem sozialer wie moralischer Ordnung"[30] . This was particularly true in the case of gold and silk embroidery, which, due to the preciousness of the materials, was reserved for sacred vestments and the garments of the nobility. The importance of identifying social status through clothing became clear in the late 13th and early 14th centuries, when the wave of city foundations led to a numerical increase in the urban bourgeoisie, which was becoming increasingly wealthy. The nobility attempted to defend its social position against the rising bourgeoisie through dress codes that reserved gold embroidery, and in some cases silk embroidery, for the nobility.[31]

Fig. 1: A woman creates an embroidery pattern by painting directly onto the embroidery base, which is stretched in a rectangular frame. Scene from the so-called Queen Mary Psalter, created around 1310-1320.- In: https://trc-leiden.nl/trc-needles/visual-archive/medieval/embroideress-queen-mary-psalter

Fig. 2: Maria works on an embroidery stretched in a frame. Scene from the Klosterneuburg Gospel Book (Austria), created around 1340, folio 25v.- In: https://www.e-codices.unifr.ch/en/sbs/0008//25v

While only female embroiderers could actually be found in the early Middle Ages, it is said "dass sich vom 11. Jahrhundert an Benediktinermönche im Süden des Reiches in St. Gallen – dort als „acupictores“ bezeichnet – in St. Emmeram in Regensburg, St. Ulrich und Afra in Augsburg und in der Abtei Weingarten nicht nur der Miniaturmalerei, sondern ebenso der Wirkerei und Stickerei widmeten"[32]. From this time on, at the latest, embroidery was no longer exclusively a women's activity, but seems to have been practiced equally in women's and men's monasteries.

Over time, embroidery seems to have become increasingly specialized and professionalized, with the actual change slowly beginning in the 11th century but then accelerating in the 13th century. Since the 13th century, references to the production of luxurious embroidery by noble women have decreased significantly in historical sources.[33] This development may have been caused by various factors: the expansion of trade since the Crusades and the wave of city foundations in the 13th century were mutually dependent and reinforced each other, while the medieval agricultural revolution, with the transition to three-field crop rotation, the use of the plow, improvements in the harnessing of draft animals, the spread of windmills, and much more occurred. The cities, which originally developed as merchant settlements, required more and more craftsmen who could reliably and punctually produce high-quality products to meet the needs of both the urban population (and increasingly wealthy farmers) and trade. It is therefore only logical that embroidery workshops were established in the 13th/14th centuries, where both women and men worked together.[34] The generally very progressive Norman kings maintained an embroidery workshop in Palermo, where, among other things, Arab embroiderers made the coronation mantle of the German emperors in 1133/34.[35] In England in 1330, 70 male and 42 female embroiderers worked in an embroidery workshop on commissions for the royal family[36] , and " anhand einer Untersuchung in London konnte nachgewiesen werden, dass der weitaus größte Teil der mittelalterlichen Kirchenstickereien in zünftisch organisierten Werkstätten ausgeführt und nicht, wie auch in Fachkreisen lange angenommen, in Klöstern hergestellt wurde."[37]

Where possible, professional embroiderers in cities joined together in guilds to provide mutual support, regulate training, and set and monitor quality. In the High Middle Ages „nahmen Frauen[…] eine erstaunlich gleichberechtigte Stellung ein. […] Ausdrücklich hatten beide Geschlechter gleiche Rechte, die gleichen Ausbildungsbedingungen und die gleichen Meisterstücke zu bewältigen"[38] . As early as 1292, embroiderers in Paris were granted guild statutes, and "eine Steuerliste von 1292 [führte] vierzehn Stickmeister- und –meisterinnen auf, die ihre Abgaben geleistet haben. Drei Jahre später wenden sich alle im Stickereigewerbe tätigen Personen – Meister, Meisterinnen und Arbeiter beiderlei Geschlechts – in einer Petition an den Provost [d.h. Bürgermeister, Anm. der Verf.]von Paris, um sich die niedergeschriebenen Statuten zur Regelung des Gewerbes bestätigen zu lassen. Von den 93 genannten Personen war nur ein Dutzend männlich. Ausgehend von den Gebräuchen anderer Handwerksarten ist davon auszugehen, dass Männer die Auftragseinwerbung und den Verkauf der fertigen Produkte innehatten, während die Ausbildung & Produktion in den Händen von Frauen lag. […]Im Jahr 1316 umfasste die Vereinigung der Sticker in Paris 179 Personen"[39] . Guilds of embroiderers already existed in Bruges in 1296 and in Ghent in 1314, which is not surprising, as Flanders was a center of textile production and trade at that time.

In Cologne, the first guild charter for coat of arms embroiderers was issued in 1397. However, there were embroiderers before that whose work was presumably of such high quality that they were mentioned by name in sources. One such embroiderer was

• the coat of arms embroiderer Luthe, the wife of the coat of arms embroiderer Johannes de Santen (1340)

• Bela, factrix Stolarum (1343)

• Guytginis, factrix casularum (1346)

• Guda, mitrifex (1350)

• Drude de Wuppervurde, operatrix casularum (1356)

• Stina de Wupervurde, stole embroiderer (1384)[40]

The following male embroiderers are recorded as active before 1397

• Johann von Santin, coat of arms embroiderer (1344)

• Emerich, coat of arms embroiderer (1368)

• Tilman, wambesticker [vest/jacket embroiderer, author's note] (1378)[41] .

These records make it clear that even in the 14th century, there was a considerable division of labor among the craftsmen who produced embroidery. In addition to coats of arms, a great deal of embroidery was obviously produced for sacred textiles, although it should be noted that "unter mitra […] damals auch eine Frauenhaube verstanden [wurde]"[42]. "Die Wappensticker beschäftigten sich keineswegs ausschließlich mit der Wappenstickerei, d. h. dem Sticken der ritterlichen Wappenröcke und Pferdedecken, auch nicht nur mit der Kunststickerei, insbesondere Paramentenstickerei, sondern sie verzierten wohl überhaupt alle besseren Kleidungsstücke mit Stickerei"[43] . All of this embroidery was done in silk. In the Cologne guilds, women and men had equal rights; the guild documents refer to masters and mistresses[44] . The extreme specialization of embroiderers in Cologne may have resulted from the city's location. Cologne was one of the largest cities of its time, played a very important role in trade with England as a Hanseatic city, possessed staple rights, and was located at the intersection of important north-south and east-west connections. As a result, the city itself was prosperous enough to commission embroidery, but also had sufficient trade relations to commission embroidery for trade.

In the 14th and 15th centuries, there were embroiderers in several German cities, but they did not always form their own guild; instead, they were grouped together with other trades in a guild. This was quite common in the Middle Ages, as a certain number of members was required to perform the tasks of a guild, especially with regard to supporting the surviving dependents of deceased masters and providing assistance to sick guild members. In Frankfurt, for example, a guild of tailors, embroiderers, and cloth shearers was established in 1377, and in 1395 embroiderers were found in the tailors' guild, as well as in Hildesheim in 1424 and in Nuremberg around 1494.[45] In these cities, however, female embroiderers did not appear to have the same rights as in Cologne. The Frankfurt guild charter of 1377 lists the conditions of admission for women and men separately. Women and children who had citizenship were also allowed to practice the craft of embroidery. However, it is not clear whether they were allowed to be masters with their own workshops. Widows of masters were allowed to continue running the workshop.[46]

Over time, embroidery seems to have become increasingly specialized and professionalized, with the actual change slowly beginning in the 11th century but then accelerating in the 13th century. Since the 13th century, references to the production of luxurious embroidery by noble women have decreased significantly in historical sources.[33] This development may have been caused by various factors: the expansion of trade since the Crusades and the wave of city foundations in the 13th century were mutually dependent and reinforced each other, while the medieval agricultural revolution, with the transition to three-field crop rotation, the use of the plow, improvements in the harnessing of draft animals, the spread of windmills, and much more occurred. The cities, which originally developed as merchant settlements, required more and more craftsmen who could reliably and punctually produce high-quality products to meet the needs of both the urban population (and increasingly wealthy farmers) and trade. It is therefore only logical that embroidery workshops were established in the 13th/14th centuries, where both women and men worked together.[34] The generally very progressive Norman kings maintained an embroidery workshop in Palermo, where, among other things, Arab embroiderers made the coronation mantle of the German emperors in 1133/34.[35] In England in 1330, 70 male and 42 female embroiderers worked in an embroidery workshop on commissions for the royal family[36] , and " anhand einer Untersuchung in London konnte nachgewiesen werden, dass der weitaus größte Teil der mittelalterlichen Kirchenstickereien in zünftisch organisierten Werkstätten ausgeführt und nicht, wie auch in Fachkreisen lange angenommen, in Klöstern hergestellt wurde."[37]

Where possible, professional embroiderers in cities joined together in guilds to provide mutual support, regulate training, and set and monitor quality. In the High Middle Ages „nahmen Frauen[…] eine erstaunlich gleichberechtigte Stellung ein. […] Ausdrücklich hatten beide Geschlechter gleiche Rechte, die gleichen Ausbildungsbedingungen und die gleichen Meisterstücke zu bewältigen"[38] . As early as 1292, embroiderers in Paris were granted guild statutes, and "eine Steuerliste von 1292 [führte] vierzehn Stickmeister- und –meisterinnen auf, die ihre Abgaben geleistet haben. Drei Jahre später wenden sich alle im Stickereigewerbe tätigen Personen – Meister, Meisterinnen und Arbeiter beiderlei Geschlechts – in einer Petition an den Provost [d.h. Bürgermeister, Anm. der Verf.]von Paris, um sich die niedergeschriebenen Statuten zur Regelung des Gewerbes bestätigen zu lassen. Von den 93 genannten Personen war nur ein Dutzend männlich. Ausgehend von den Gebräuchen anderer Handwerksarten ist davon auszugehen, dass Männer die Auftragseinwerbung und den Verkauf der fertigen Produkte innehatten, während die Ausbildung & Produktion in den Händen von Frauen lag. […]Im Jahr 1316 umfasste die Vereinigung der Sticker in Paris 179 Personen"[39] . Guilds of embroiderers already existed in Bruges in 1296 and in Ghent in 1314, which is not surprising, as Flanders was a center of textile production and trade at that time.

In Cologne, the first guild charter for coat of arms embroiderers was issued in 1397. However, there were embroiderers before that whose work was presumably of such high quality that they were mentioned by name in sources. One such embroiderer was

• the coat of arms embroiderer Luthe, the wife of the coat of arms embroiderer Johannes de Santen (1340)

• Bela, factrix Stolarum (1343)

• Guytginis, factrix casularum (1346)

• Guda, mitrifex (1350)

• Drude de Wuppervurde, operatrix casularum (1356)

• Stina de Wupervurde, stole embroiderer (1384)[40]

The following male embroiderers are recorded as active before 1397

• Johann von Santin, coat of arms embroiderer (1344)

• Emerich, coat of arms embroiderer (1368)

• Tilman, wambesticker [vest/jacket embroiderer, author's note] (1378)[41] .

These records make it clear that even in the 14th century, there was a considerable division of labor among the craftsmen who produced embroidery. In addition to coats of arms, a great deal of embroidery was obviously produced for sacred textiles, although it should be noted that "unter mitra […] damals auch eine Frauenhaube verstanden [wurde]"[42]. "Die Wappensticker beschäftigten sich keineswegs ausschließlich mit der Wappenstickerei, d. h. dem Sticken der ritterlichen Wappenröcke und Pferdedecken, auch nicht nur mit der Kunststickerei, insbesondere Paramentenstickerei, sondern sie verzierten wohl überhaupt alle besseren Kleidungsstücke mit Stickerei"[43] . All of this embroidery was done in silk. In the Cologne guilds, women and men had equal rights; the guild documents refer to masters and mistresses[44] . The extreme specialization of embroiderers in Cologne may have resulted from the city's location. Cologne was one of the largest cities of its time, played a very important role in trade with England as a Hanseatic city, possessed staple rights, and was located at the intersection of important north-south and east-west connections. As a result, the city itself was prosperous enough to commission embroidery, but also had sufficient trade relations to commission embroidery for trade.

In the 14th and 15th centuries, there were embroiderers in several German cities, but they did not always form their own guild; instead, they were grouped together with other trades in a guild. This was quite common in the Middle Ages, as a certain number of members was required to perform the tasks of a guild, especially with regard to supporting the surviving dependents of deceased masters and providing assistance to sick guild members. In Frankfurt, for example, a guild of tailors, embroiderers, and cloth shearers was established in 1377, and in 1395 embroiderers were found in the tailors' guild, as well as in Hildesheim in 1424 and in Nuremberg around 1494.[45] In these cities, however, female embroiderers did not appear to have the same rights as in Cologne. The Frankfurt guild charter of 1377 lists the conditions of admission for women and men separately. Women and children who had citizenship were also allowed to practice the craft of embroidery. However, it is not clear whether they were allowed to be masters with their own workshops. Widows of masters were allowed to continue running the workshop.[46]

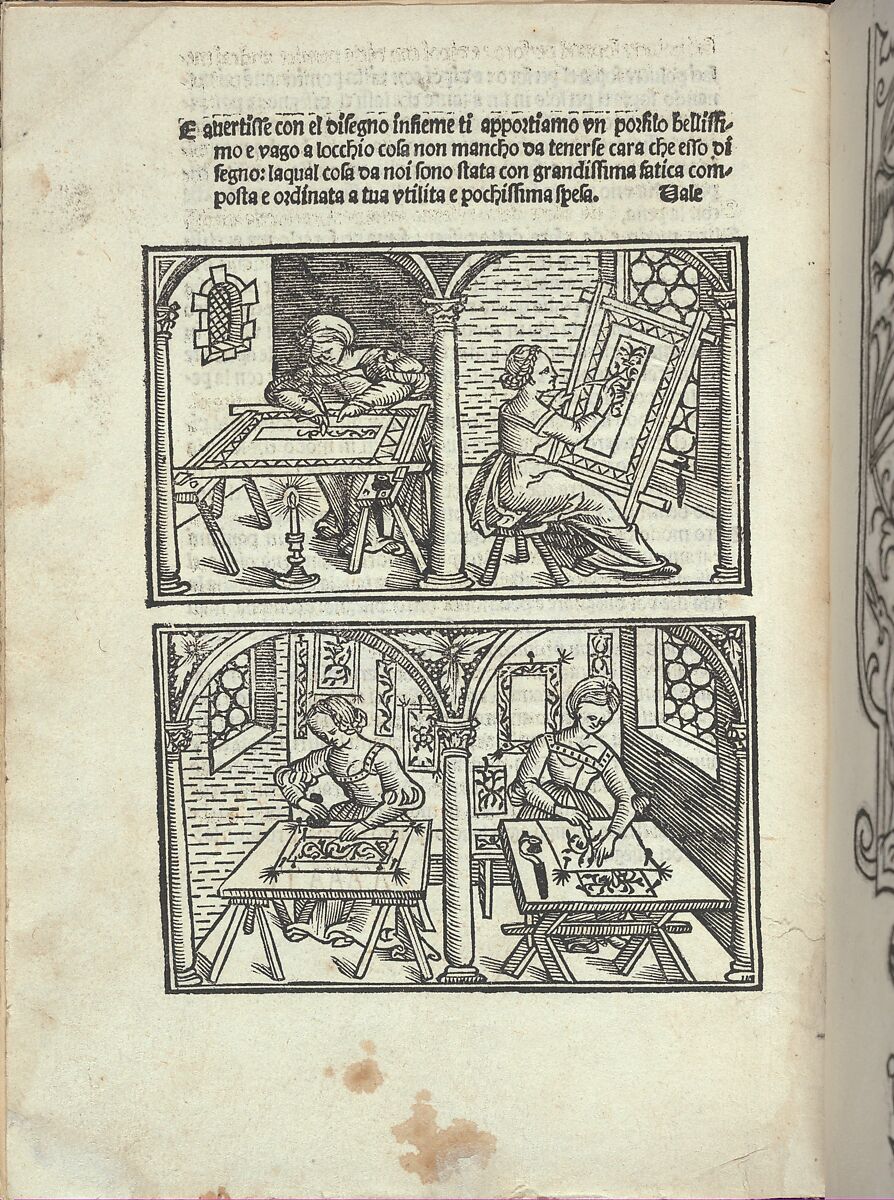

Fig. 3: Women piercing or tracing embroidery patterns. Woodcut from Alessandro Paganino, Libro de ricami, around 1532.- In: https://www2.cs.arizona.edu/patterns/weaving/books/pap_lace.pdf

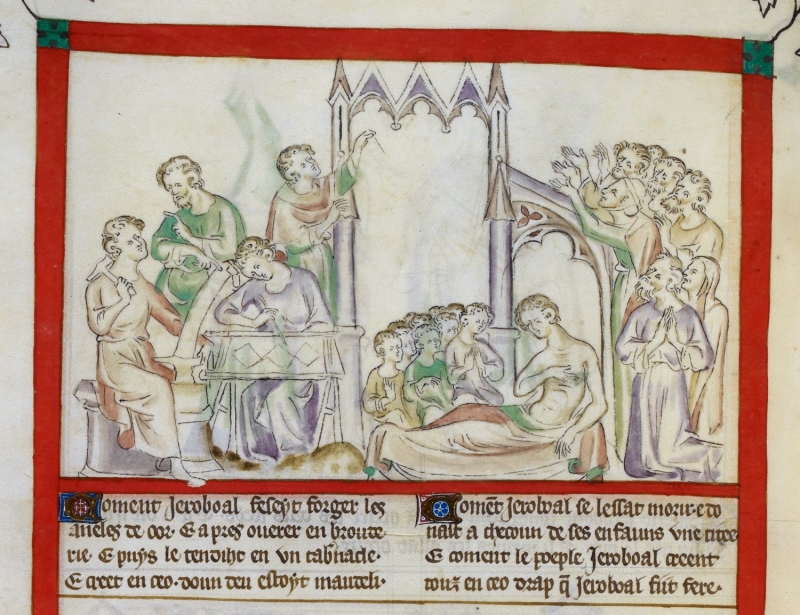

Fig. 4: Bezalel and Oholiab working on embroidery for the temple. Scene from the Book of Exodus from a picture Bible created in the style of Giotto, Padua, around 1400.- In: Staniland, Kai: Embroideres, London 1991, S. 27

In England, there is evidence that the textiles purchased for the household of Edward III (1312–1377), including embroidery, were produced equally by women and men, even though written sources suggest that in the 13th and 14th centuries, embroidery was predominantly produced by women.[47] Between 1239 and 1244, Mabel of Bury St. Edmunds received several commissions from the royal court and remained so well remembered by King Henry III that he gave her a gift years later.[48] Maud de Benetleye and Joan de Wobum also worked for the court; Maud of Canterbury worked for the king's half-sister, Alice de Lusignan. The financial records of the English royal court mention a Christiana de Enfield several times. In 1303, in preparation for a trip to France by the English queen Margaret, she was commissioned to embroider silk cushions, bed covers, canopies, and curtains with 2,800 lilies and leopards (=heraldic lions), the emblems of the kingdoms of England and France, in her workshop. She carried out the commission together with Catherine of Lincoln.[49] Johanna Heyroun made chasubles for the royal chapel in 1327-28, and Matilda la Settere worked in the king's own embroidery workshop at court.[50]

Male embroiderers are also documented. In 1307, the mayor of London attested to the payment of a partial sum to the embroiderer Alexandre le Settre. In 1308, John Bonde and John de Stebenheth delivered an embroidered cloak intended for the bishop of Worcester to the mayor, while the mayor assured them that the work would be paid for in "certain installments, one fourth being the share of Margery, wife of John Stebenheth, and a fourth to Katherine, daughter of Simon Godard of full age, and the remainder to John Bonde for the use of Thomas and Simon, children of Simon Godard"[51] . In 1325, part of the amount owed was still unpaid.[52] This information makes it clear that embroidery was produced in workshops in London and that several people worked on a single piece if the embroidery was very extensive.[53] However, an embroidery guild was not founded and recognized until 1561.[54]

The embroiderers of the High and Late Middle Ages were not necessarily the designers of the embroidered works. Rather, the design often came from painters who applied the preliminary sketch to the fabric and supervised the execution of the embroidery[55] . The Cologne guild master of 1470, Johann von Bornheim, lived in the same house as Stephan Lochner for a time, so it can be assumed that Lochner made designs for his friend Bornheim. Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528) is known to have designed embroideries.[56] The design drawings were either applied directly to the embroidery ground or transferred to the embroidery ground using the so-called hole tracing method.[57] In the latter process, the drawing was placed on the embroidery ground and holes were pricked along the lines of the drawing with a needle. The paper was then sprinkled with colored powder so that the dots became visible on the embroidery ground, which, when connected to form lines, created the outlines of the shapes to be embroidered. Preliminary sketches seem to have already existed for the above-mentioned antipedes and other white embroidery.[58]

Apparently, embroiderers also used templates created by artists. These drawings were probably originally intended for painters, glass painters, and miniature painters[59], but could certainly also be used as templates for embroidery. One of the surviving model books is the Pepysian model book, which was created in the second half of the 14th century.[60] Notes, names, and comments written in the book indicate that the surviving copy was used by various people and passed on from one to another.[61]

In summary, it can be said that both women and men embroidered in the Middle Ages. Insofar as embroidery was done commercially, there were female and male professional embroiderers who were organized in guilds and worked there on an equal footing, except for the lack of passive and active voting rights in the council of the respective city. When embroidery was not done commercially, it was predominantly carried out by noblewomen and (noble) nuns, whose circumstances allowed them the time necessary for the production of embroidery. Presumably, the fact that textiles embroidered for ecclesiastical use were preserved more carefully for the reasons mentioned above and are therefore more frequently found, among other factors that will be discussed below, contributed to the belief that embroidery was fundamentally a woman's work until well into the 20th century.

Male embroiderers are also documented. In 1307, the mayor of London attested to the payment of a partial sum to the embroiderer Alexandre le Settre. In 1308, John Bonde and John de Stebenheth delivered an embroidered cloak intended for the bishop of Worcester to the mayor, while the mayor assured them that the work would be paid for in "certain installments, one fourth being the share of Margery, wife of John Stebenheth, and a fourth to Katherine, daughter of Simon Godard of full age, and the remainder to John Bonde for the use of Thomas and Simon, children of Simon Godard"[51] . In 1325, part of the amount owed was still unpaid.[52] This information makes it clear that embroidery was produced in workshops in London and that several people worked on a single piece if the embroidery was very extensive.[53] However, an embroidery guild was not founded and recognized until 1561.[54]

The embroiderers of the High and Late Middle Ages were not necessarily the designers of the embroidered works. Rather, the design often came from painters who applied the preliminary sketch to the fabric and supervised the execution of the embroidery[55] . The Cologne guild master of 1470, Johann von Bornheim, lived in the same house as Stephan Lochner for a time, so it can be assumed that Lochner made designs for his friend Bornheim. Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528) is known to have designed embroideries.[56] The design drawings were either applied directly to the embroidery ground or transferred to the embroidery ground using the so-called hole tracing method.[57] In the latter process, the drawing was placed on the embroidery ground and holes were pricked along the lines of the drawing with a needle. The paper was then sprinkled with colored powder so that the dots became visible on the embroidery ground, which, when connected to form lines, created the outlines of the shapes to be embroidered. Preliminary sketches seem to have already existed for the above-mentioned antipedes and other white embroidery.[58]

Apparently, embroiderers also used templates created by artists. These drawings were probably originally intended for painters, glass painters, and miniature painters[59], but could certainly also be used as templates for embroidery. One of the surviving model books is the Pepysian model book, which was created in the second half of the 14th century.[60] Notes, names, and comments written in the book indicate that the surviving copy was used by various people and passed on from one to another.[61]

In summary, it can be said that both women and men embroidered in the Middle Ages. Insofar as embroidery was done commercially, there were female and male professional embroiderers who were organized in guilds and worked there on an equal footing, except for the lack of passive and active voting rights in the council of the respective city. When embroidery was not done commercially, it was predominantly carried out by noblewomen and (noble) nuns, whose circumstances allowed them the time necessary for the production of embroidery. Presumably, the fact that textiles embroidered for ecclesiastical use were preserved more carefully for the reasons mentioned above and are therefore more frequently found, among other factors that will be discussed below, contributed to the belief that embroidery was fundamentally a woman's work until well into the 20th century.