Prevalence and Frequency of Cross-Stitch in the Middle Ages

Cross-stitch embroidery requires a uniformly woven fabric as its base material, i.e., a fabric with an even number of warp and weft threads, which makes it possible to count the threads over which the embroidery stitches are made. Linen, which was already used by the Germanic tribes for clothing, is particularly suitable for this purpose[1]. Flax, from which linen threads were ultimately spun, is a very old cultivated plant that was widespread throughout Northern Europe. The weaving process could produce linen cloths of varying densities, so that the possible uses of linen were manifold. During the Middle Ages, linen cloth was produced both in rural households and in large quantities for trade by guild-affiliated craftsmen in the cities.

The availability and easy accessibility of the raw material actually suggest that thread-bound counted stitches are not much younger than the knowledge of how to produce the raw material. Nevertheless, research shows that "der Kreuzstich […] in mittelalterlichen Stickereien und denen der Renaissance zwar bekannt [war] und auch schon als ´Creutzstich´bezeichnet […] in den erhaltenen Stickereien aber selten angewandt[2] wurde.

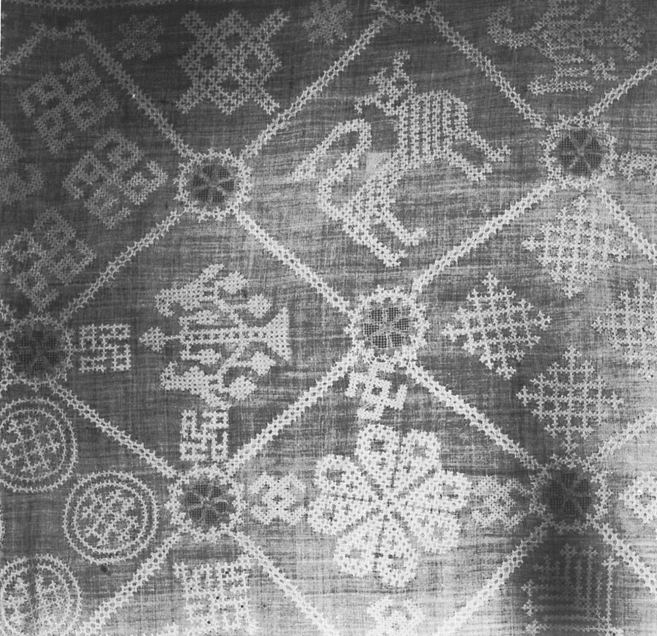

The aforementioned embroidered cloths date from between 1260 and the late 14th century. Apart from the cloths presented here, there are only a few embroidered textiles in which cross-stitch was also used. It is possible that a blanket, the purpose of which I was unable to determine but which, based on its dimensions, could have been an altar cloth, was embroidered with cross-stitch in the second half of the 13th century at the Isenhagen monastery. In any case, the available photo, which shows a section of the blanket, suggests that it was cross-stitch.[3] Kroos mentions a lectern cover made of sturdy white linen, which dates from the mid-14th century and is embroidered with herringbone stitch, chain stitch, and a little cross stitch.[4] Another lectern cloth, also dating from the mid-14th century, features heraldic double eagles in geometric frames and is embroidered with herringbone's stitch, chain stitch, and cross stitch.[5] Cross stitch is also just one of several embroidery techniques used on an antependium from Hildesheim, which dates from 1410/20. It is used for frame fillings alongside running stitch and herringbone stitch, while couching stitch and appliqué techniques are used for other parts of the antependium. [6]

Fig. 1: Detail of lectern cover from Isenhagen Monastery, 2nd half of the 13th century.- In: https://i.pinimg.com/736x/f4/ff/73/

f4ff7346b7b934b95c3d8c9796899ee1--medieval-embroidery-linen-tablecloth.jpg

f4ff7346b7b934b95c3d8c9796899ee1--medieval-embroidery-linen-tablecloth.jpg

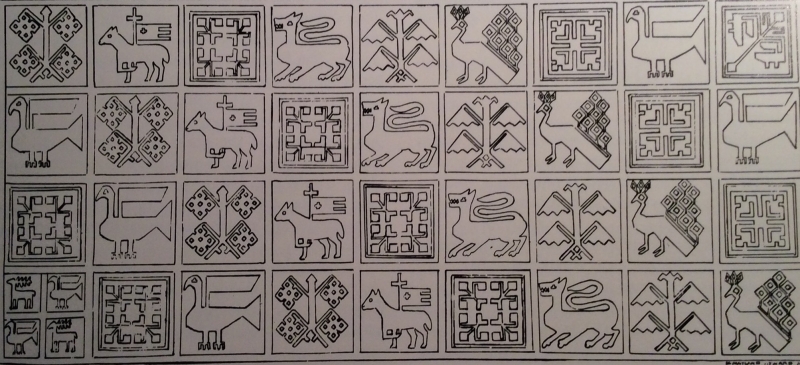

Fig. 2: Reconstruction of the cushion pattern from the tomb of the Archbishop of York, Walter de Gray (1215-1255).- In: https://trc-leiden.nl/trc-needles/individual-textiles-and-textile-types/fragments-and-panels/tomb-of-archbishop-walter-de-gray#:~:text=The%20tomb%20was%20opened%20in,%2C%20

perhaps%20linen%2C%20had%20disintegrated

perhaps%20linen%2C%20had%20disintegrated

Outside Germany, cross-stitch work was not found in Europe until the 13th century. Among other embroidery techniques, an inventory of St. Paul's Cathedral from 1295 mentions the so-called opus pulvinarium, which refers to canvas work, including cross-stitch.[7] Another name for opus pulvinarium is "cushion style," because cross-stitch was often used for "cushions, upon which to sit or to kneel in church, or uphold the mass-book at the altar"[8] as well as for coat of arms embroidery. Coatsworth cites as an example of opus pulvinarium "an amice with little shields"[9] from the inventory of St. Paul's, which may have been the reason why opus pulvinarium is seen as an "appropriate technique for heraldic subjects."[10] As another example of cross-stitch work, she cites a cushion that was found in the tomb of Walter de Grey, Archbishop of York. The archbishop died in 1255, so the cushion must have been made before that date.[11] A fragment of embroidery made of gold and silver threads has been preserved, while the base material, presumably linen, has disintegrated. The pattern of the cushion was reconstructed from the fragments found.[12]

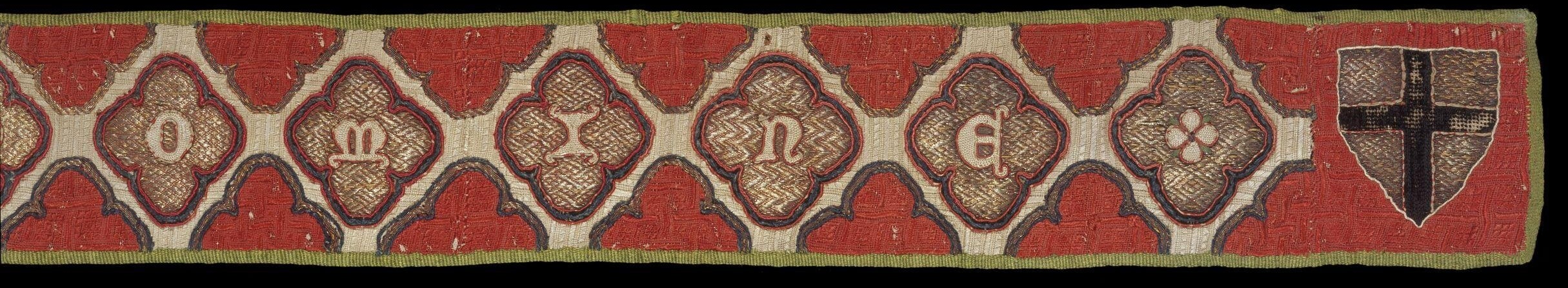

Cross-stitch was also used for the hem of the Syon Cope, which Bradley dates to 1225,[13] but the Victoria & Albert Museum dates to 1310-1320.[14] What seems unusual here is that cross-stitch appears on a work of opus anglicanum, even if it is only the edging of the main embroidery. Coatsworth cites another example of canvas stitches in an altar cloth[15] bearing the inscription "Donna Johanna Beverlai monaca me fecit" on the reverse side[16] and probably dating from the first half of the 13th century. Coatsworth classifies this piece as canvas work; although it is worked on a linen ground, it features only "diagonal, tent, plait and stem stitches, detached twisted buttonhole stitch over padding, laid and couch work"[17], but no cross stitch. Either this is an erroneous classification, or the term opus pulvinarium or canvas work is not synonymous with cross stitch.

Fig. 3: Detail of the Syon cope with parts of the hem.

In: https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/the-syon-cope?srsltid

=AfmBOopFgm94orS9VPDF7DJHXHtVThWsbcJRPAocokyfTdqD2K5hq8z6

In: https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/the-syon-cope?srsltid

=AfmBOopFgm94orS9VPDF7DJHXHtVThWsbcJRPAocokyfTdqD2K5hq8z6

Fig. 4: Detail of the altar cloth made by Johanna Beverlai.-

In: https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O111536/frontal-band-beverlai-johanna-domna/

In: https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O111536/frontal-band-beverlai-johanna-domna/

Overall, it seems to me that the number of identifiable medieval embroideries in which cross-stitch was used is quite small. It is also surprising that cross-stitch embroidery was apparently not common before the 13th century, especially since cross-stitch is relatively easy to embroider compared to couching work. This raises the question of whether there may have been more cross-stitch works than are known today or mentioned in the literature. Unfortunately, not all museums, especially the smaller ones, are participating in the digitization of their existing artworks so that they can be viewed online and the museums can be contacted accordingly. At least the Internet offers the Bildindex der Kunst und Architektur, which provides black-and-white photographs of textile artworks.[18] However, the accompanying information does not always reveal where the respective artwork is kept or displayed; sometimes the museums named as storage locations no longer exist. The photographs show a number of embroideries, but in very few cases do they reveal the embroidery technique used.

Of course, in this context, the question of why so few finds have been made must also be asked. Heidrich points out that "die Anzahl der uns erhaltenen mittelalterlichen Textilien aus dem Zeitraum bis zum Ende des 11.Jahrhunderts [stammen und] ihr Überleben dem Gebrauch im sakralen Bereich verdanken."[19] Sacred textiles were often deliberately preserved in the Middle Ages and kept in church treasuries, especially since they were often seen as "durch Segnungen oder als Reliquien unter einem besonderen Schutz,"[20] which meant they were not reused.[21] Many of them were "über die Jahrhunderte hinweg bewahrt und gepflegt, teilweise sogar mit jahrhundertelanger Dokumentation von Eingriffen oder Erhaltungsmaßnahmen."[22] The condition of textiles naturally depends on how they were stored. In particular, textiles that were used to clothe the deceased in crypt burials or that were part of the coffin's furnishings often remained in relatively good condition. This is especially true in the case of the burial of high-ranking dignitaries, but also generally true for wealthy people who could afford a crypt burial. Crypts enabled "die gewünschte, möglichst weitgehende körperliche Erhaltung des Leichnams, um die Auferstehung am Jüngsten Tage zu erleichtern."[23] In contrast to burials in the ground, "Trockenheit, stetiger Luftzug und der Ausschluss von Tierbefall [verhinderten weitgehend] den Zerfall von Textilien."[24] Occasionally, only parts of a textile decayed, as can be seen in the tomb of the Archbishop of York, Walter de Grey. As mentioned, only the embroidery remained of the pillow found in the tomb, while the fabric underneath had disintegrated.

A low density of finds can also be caused by external events. It is generally assumed that during the wave of plague from 1346 to 1353, which became known as the "Black Death" and which, according to estimates, claimed between 33% and 60% of the European population[25], the production of embroidery declined significantly[26], especially since the plague hit the urban population particularly hard, including many craftsmen who produced embroidery and wealthy citizens who bought it. The late medieval agricultural crisis, which was a major factor in the emergence of deserted villages and was accompanied by a decline in the prosperity of the noble landowners, may also have contributed to this. Like other works of art, embroidery was repeatedly destroyed by fires, uprisings, and wars and the accompanying destruction, most recently on a large scale at the end of World War II, as already explained in the case of the altar cloth from Fulda. It is in the nature of things that wear and tear also played a role in the loss of embroidered textiles.[27] A significant reduction in stocks can also be attributed to the Reformation. Monasteries and churches were often robbed of their wealth or abolished, so that their inventory passed into foreign ownership, often that of the respective sovereigns. In order to help finance the Reformation wars, many of the precious embroidered textiles were cut up or burned to recover the valuable gold and silver threads and precious stones. [28] Of those that remained, many probably fell victim to a lack of care in secular hands.

Based on these considerations, it remains unclear whether cross-stitch was used more frequently than the surviving embroideries suggest.

Of course, in this context, the question of why so few finds have been made must also be asked. Heidrich points out that "die Anzahl der uns erhaltenen mittelalterlichen Textilien aus dem Zeitraum bis zum Ende des 11.Jahrhunderts [stammen und] ihr Überleben dem Gebrauch im sakralen Bereich verdanken."[19] Sacred textiles were often deliberately preserved in the Middle Ages and kept in church treasuries, especially since they were often seen as "durch Segnungen oder als Reliquien unter einem besonderen Schutz,"[20] which meant they were not reused.[21] Many of them were "über die Jahrhunderte hinweg bewahrt und gepflegt, teilweise sogar mit jahrhundertelanger Dokumentation von Eingriffen oder Erhaltungsmaßnahmen."[22] The condition of textiles naturally depends on how they were stored. In particular, textiles that were used to clothe the deceased in crypt burials or that were part of the coffin's furnishings often remained in relatively good condition. This is especially true in the case of the burial of high-ranking dignitaries, but also generally true for wealthy people who could afford a crypt burial. Crypts enabled "die gewünschte, möglichst weitgehende körperliche Erhaltung des Leichnams, um die Auferstehung am Jüngsten Tage zu erleichtern."[23] In contrast to burials in the ground, "Trockenheit, stetiger Luftzug und der Ausschluss von Tierbefall [verhinderten weitgehend] den Zerfall von Textilien."[24] Occasionally, only parts of a textile decayed, as can be seen in the tomb of the Archbishop of York, Walter de Grey. As mentioned, only the embroidery remained of the pillow found in the tomb, while the fabric underneath had disintegrated.

A low density of finds can also be caused by external events. It is generally assumed that during the wave of plague from 1346 to 1353, which became known as the "Black Death" and which, according to estimates, claimed between 33% and 60% of the European population[25], the production of embroidery declined significantly[26], especially since the plague hit the urban population particularly hard, including many craftsmen who produced embroidery and wealthy citizens who bought it. The late medieval agricultural crisis, which was a major factor in the emergence of deserted villages and was accompanied by a decline in the prosperity of the noble landowners, may also have contributed to this. Like other works of art, embroidery was repeatedly destroyed by fires, uprisings, and wars and the accompanying destruction, most recently on a large scale at the end of World War II, as already explained in the case of the altar cloth from Fulda. It is in the nature of things that wear and tear also played a role in the loss of embroidered textiles.[27] A significant reduction in stocks can also be attributed to the Reformation. Monasteries and churches were often robbed of their wealth or abolished, so that their inventory passed into foreign ownership, often that of the respective sovereigns. In order to help finance the Reformation wars, many of the precious embroidered textiles were cut up or burned to recover the valuable gold and silver threads and precious stones. [28] Of those that remained, many probably fell victim to a lack of care in secular hands.

Based on these considerations, it remains unclear whether cross-stitch was used more frequently than the surviving embroideries suggest.