Embroidery in Prehistory and Early History

It is extremely difficult to find evidence of embroidery, and even more so of individual embroidery techniques such as cross-stitch, in prehistory and early history in Central Europe north of the Alps. Written sources and remains from this period do not exist due to the general absence of written records. Therefore, we can only rely on remains from prehistoric pile dwellings (5th-1st millennium BC) and the salt mines of the Hallstatt culture (approx. 800-400 BC), as well as textiles that have been preserved by corrosion of the metals that wrapped them[1]. In the pile dwelling finds, "dank der dauerfeuchten Sedimente [bleiben]nämlich organische Reste wie Samen und Früchte, Bauhölzer, Holzartefakte, Tierknochen, aber eben auch feinste Geflechte und Gewebe unter Luftsauerstoff-Abschluss über die Jahrtausende hinweg erhalten. Anhand der Jahrringdatierungs-Methode, der sog. Dendrochronologie, können diese Hinterlassenschaften zudem sehr genau datiert werden"[2]

"Die seltenen erhaltenen, zum Teil über 5500 Jahre alten Fragmente zeigen eine Beherrschung des Handwerks, hervorragende Kenntnisse bei der Materialwahl und komplizierte technische Abläufe"[3]. Despite the good condition of some of the finds, they are the subject of scientific controversy, which remains a hot topic despite the findings of experimental archaeology.

Based on the finds, it is undisputed that needles with eyes have existed since the Paleolithic period (until 6000 BC). They were made of wood, bone, horn, copper, and later bronze[4]. "Die bronze-, urnenfelder- und hallstattzeitlichen Textilien weisen ein breites Spektrum an Feinheiten, Bindungsarten, Mustern und Farben auf. Weiters (sic!) geben uns die Textilien durch die verschiedenen Säume, Nähte, Ziernähte und Flickungen Auskunft über Nähtechniken"[5]. Grömer emphasizes that "spätestens ab der Bronzezeit […] die Nähkunst mit verschiedenen Sticharten bereits voll entwickelt war" and that "im Prinzip schon alle Techniken [existierten], die in der Handnäherei bis in vorindustrieller Zeit, gar bis heute, üblich sind"[6]. Grömer lists the overcast stitch, hem stitch, and running stitch as common sewing techniques[7], and Mautendorfer also mentions the sewing on of decorative elements as a task of sewing, in addition to darning and mending .[8]

Fig. 1: Late Neolithic textile from Murten, Switzerland. Fabric with sewn-on fruit pits.- In: Grömer, Karina: Prähistorische Textilkunst in Mitteleuropa. Geschichte des Handwerkes und

Kleidung vor den Römern, Wien 2010, S. 282

Kleidung vor den Römern, Wien 2010, S. 282

The loom[9] has been around since the Neolithic period and can be considered the first machine ever invented by humankind. In addition to producing fabrics with different weaves, the technique of "flying thread" was also used, which allowed additional patterns to be incorporated into the fabric during the weaving process[10]. The tablet weaving technique was mainly used to produce braids[11], of which Johanna Banck-Burgess provides an example from the Early Iron Age, the princely tomb of Eberdingen-Hochdorf (around 550 BC)[12].

Fig. 2: Remains of the braid from the princely tomb of Eberdingen-Hochdorf.- In: Banck-Burgess, Johanna: Wissensvermittlung auf dem Prüfstand Ein Beitrag experimenteller Archäologie zur Textilarchäologie.- Denkmalpflege in Baden-Württemberg 1 (2017), S. 48

Fig. 3: Reconstruction of the border from the princely tomb of Eberdingen-Hochdorf.- In: Banck-Burgess, Johanna: Wissensvermittlung auf dem Prüfstand Ein Beitrag experimenteller Archäologie zur Textilarchäologie.- Denkmalpflege in Baden-Württemberg 1 (2017), S. 48

Scientific controversy focuses largely on the question of whether certain textile finds feature embroidery or whether the patterns were woven using the "flying thread" technique. One example is a textile find from a pile dwelling settlement near Pfäffikon-Irgenhausen (Switzerland), which dates from 1700-1440 BC.

Fig. 4: Breakdown of the pattern of the textile find from Irgenhausen, Figs. a, c, and e show the direction of the stitches,

Figs. b, d, and f show the appearance on the front of the fabric.- In: Jorgensen, Lise Bender u,a.: Creativity in the Bronze Age. Understanding Innovation in Pottery, Textile, and Metalwork Production , Cambridge 2018, S. 259

Figs. b, d, and f show the appearance on the front of the fabric.- In: Jorgensen, Lise Bender u,a.: Creativity in the Bronze Age. Understanding Innovation in Pottery, Textile, and Metalwork Production , Cambridge 2018, S. 259

Fig. 5: Reconstruction of the "art fabric" from Irgenhausen.- In: Banck-Burgess, Johanna: Wissensvermittlung auf dem Prüfstand Ein Beitrag experimenteller Archäologie zur Textilarchäologie.- Denkmalpflege in Baden-Württemberg 1 (2017), S. 52

In 2010 and 2016

[13], Karina Grömer describes this textile as follows: "The fine linen was woven, then decorated with embroidery. The rich pattern consists of chessboard patterns, triangles, and stripes. Older dye analysis proves that the patterns were carried out in blue, red, violet, and yellow on a natural white linen ground weave."[14] She describes the embroidery techniques as a "Kombination[en] aus Stiel-, Rück, Vor- und einer Art Kreuzstich"[15] , citing both Antoinette Rast-Eicher and Emil Vogt, who was the first to describe the find in detail in 1937. He "bezeichnete es […] als broschiert mit Dreiecken und Schachbrettmustern. Er gibt auch in Schemazeichnungen die komplexen Fadenführungen wieder – sie flottieren teils in Schussrichtung, teils in Kettrichtung, aber auch schräg. Der Richtungsverlauf ist von den verschiedenen Musterfeldern abhängig, sehr variationsreich und aufwändig. Die Musterung besteht aus großen gefüllten Dreiecken, getrennt durch horizontale Bänder mit schachbrettartigen Mustern, eingefasst von Bändern in Schachbrettmuster."[16] Johanna Banck-Burgess adds a further argument from Rast-Eicher's reasoning, pointing out that this refers to the piercing of the base fabric[17] , which necessarily occurs during embroidery.

Banck-Burgess, on the other hand, believes that the pattern on the textile from Irgenhausen was incorporated into the fabric during the weaving process[18] . She bases this opinion on research conducted by Hildegard Igel, who used experimental archaeology methods. Igel assumes that incorporating the colored pattern threads into the weaving process would not have been a problem. Furthermore, there are very few threads whose stitching is visible, which would inevitably occur when embroidering. On the back of the checkerboard pattern, there are numerous continued threads (meaning: the color that does not appear on the front), which would have been avoided when embroidering due to the waste of yarn. Igel explains the punctures in the base fabric identified by Rast-Eicher as stitch holes as corrections of weaving errors, in which individual weaving threads were pulled out and replaced[19] . She thus concludes that "die Musterfäden […] während des Webens in vertikaler, horizontaler und diagonaler Richtung eingeschlungen [wurden]. Diese Art der Herstellung wird als „Soumak“ bezeichnet und wurde viele Jahrhunderte später auch bei den frühkeltischen Textilien angewandt. In seiner Herstellungstechnik ist das Gewebe unter den Pfahlbautextilien bisher einzigartig, zeigt aber zugleich auch schlaglichtartig, wie hochstehend die Weberei in dieser Zeit war."[20].

Banck-Burgess, on the other hand, believes that the pattern on the textile from Irgenhausen was incorporated into the fabric during the weaving process[18] . She bases this opinion on research conducted by Hildegard Igel, who used experimental archaeology methods. Igel assumes that incorporating the colored pattern threads into the weaving process would not have been a problem. Furthermore, there are very few threads whose stitching is visible, which would inevitably occur when embroidering. On the back of the checkerboard pattern, there are numerous continued threads (meaning: the color that does not appear on the front), which would have been avoided when embroidering due to the waste of yarn. Igel explains the punctures in the base fabric identified by Rast-Eicher as stitch holes as corrections of weaving errors, in which individual weaving threads were pulled out and replaced[19] . She thus concludes that "die Musterfäden […] während des Webens in vertikaler, horizontaler und diagonaler Richtung eingeschlungen [wurden]. Diese Art der Herstellung wird als „Soumak“ bezeichnet und wurde viele Jahrhunderte später auch bei den frühkeltischen Textilien angewandt. In seiner Herstellungstechnik ist das Gewebe unter den Pfahlbautextilien bisher einzigartig, zeigt aber zugleich auch schlaglichtartig, wie hochstehend die Weberei in dieser Zeit war."[20].

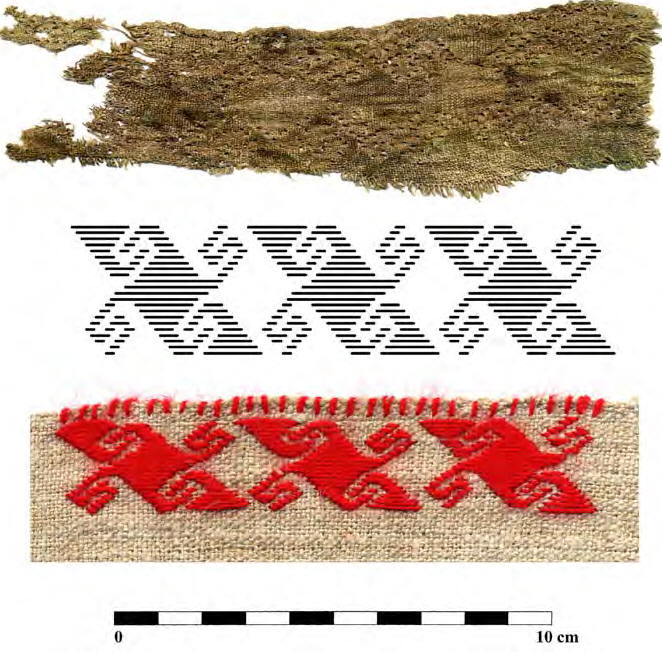

Another example of "genuine" embroidery that has sparked controversy comes from a burial find from the Late Iron Age in Nové Zamky (Slovakia). It is a "leinwandbindige[s] Gewebe […] aus Flachs […]mit sehr ausgeprägte{n] Einstichlöcher[n], in denen sich noch teils Stickfäden aus roter Wolle erhalten haben. Entlang der Stichführung sind Verziehungen des Stoffes zu beobachten. […]Das Muster […] wurde als S-Muster bzw. als ineinandergreifende Trompetenmotive beschrieben. Das gestickte Motiv erscheint kurviger als die stark geometrischen eingewobenen Muster."[21]

Fig. 6: Embroidered fabric from Nové Zamky, Slovakia.- In: Karina Grömer, Colour, Pattern and Glamour. Textiles in Central Europe 2000-400 BC. - Proceedings of the Vth International Symposium on Textiles and Dyes in the Ancient Mediterranean World

(Montserrat, 19-22 March, 2014) S. 42

Fig. 7: Hallstatt salt mine find. Fabric with decorative seam, Early Iron Age.- In: Grömer, Karina: The Art of Prehistoric

Textile Making. The development of craft traditions

and clothing in Central Europe, Wien 2016, S. 204

Grömer cites a fabric from Hallstatt as another example of decorative embroidery. Here, a rectangular piece of fabric was inserted into an existing fabric. The seam was covered on the visible side with a dense loop stitch in blue and white. Four rows of stem stitches, also in blue and white, can be found on the rolled hem edge.[22]

In view of these finds and the conflicting opinions among scholars, Banck-Burgess defines the term "embroidery" by distinguishing between ornamental embroidery and functional embroidery. According to this definition, ornamental embroidery is applied to a fabric base that is reduced to the function of carrying a decoration. Functional embroidery, on the other hand, can cover structural elements such as gussets or repairs to a fabric, or prevent fabric edges from fraying. In all these cases, functional embroidery can coincidentally also be decorative, without the fabric base being reduced to a carrier function[23] . Banck-Burgess categorically states : "Prähistorische Textilien waren keine Verzierungsträger."[24] If one follows this definition, there appears to be no embroidery in Central Europe until the turn of the millennium, as people apparently gave priority to decoration using weaving techniques. The reasons for this must remain speculative, just as Banck-Burgess's assertion ultimately remains unproven and is based on her own definition, especially since it would be illogical to use decorative stitches for repairs and seams if the intention was not to add decoration. In this respect, Banck-Burgess's distinction seems somewhat far-fetched. In view of the controversial opinions of scholars, one can only attribute the first occurrence of cross-stitch in Central Europe to the textile fabric from Irgenhausen with extreme caution.

However, it is undisputed that in Central European prehistory and early history, it was generally preferred to decorate fabrics by weaving or printing, so that embroidery is extremely rare.

However, it is undisputed that in Central European prehistory and early history, it was generally preferred to decorate fabrics by weaving or printing, so that embroidery is extremely rare.