Renaissance Cross-Stitch

The chapter on cross-stitch in the early modern period has already explained the reasons for the significant increase in cross-stitch embroidery during this period, which was carried out by women from the upper and middle classes. This chapter will add further factors that have emerged from studies limited to England and may not apply to the same extent, or perhaps not at all, to other European countries, with the possible exception of France. In any case, they have not been studied to the same extent as the embroideries of Mary, Queen of Scots (1542–1587) and Bess of Hardwick (Elizabeth Talbot, Countess of Shrewsbury, 1527–1608), which are the focus of this study.

More than 100 pieces of embroidered fabric by Mary Stuart and Bess of Hardwick have been preserved, which can be attributed to the quality of the embroidery as well as the fact that they were considered particularly important due to the social status of the two ladies.[1] Their work is part of a new flowering of English embroidery after the plague and wars of the 14th and 15th centuries contributed to the decline of the famous opus anglicanum embroidery of the High Middle Ages.[2]

The embroideries were created between 1569 and 1584, when Mary Stuart was held captive by Queen Elizabeth I in the care of George Talbot, Earl of Shrewsbury, and his wife Elizabeth, known as Bess of Hardwick. Both Mary Stuart and Bess of Hardwick were enthusiastic embroiderers. During her marriage to Francis II of France, Mary had the opportunity to develop outstanding embroidery skills, as her mother-in-law, Catherine de Medici, was a passionate embroiderer. Bess, on the other hand, grew up as the daughter of a family of minor nobility. Despite the interruption of England's great embroidery tradition, embroidery had always remained an element of the education of daughters from noble families or daughters of the gentry.[3] In this respect, there was a basis for Bess of Hardwick, who ultimately acted as Mary's guardian, and Mary Stuart to become friends and work together. Among the ladies who embroidered together with Mary Stuart and Bess of Hardwick were Lady Mary Livingston and Mrs. Mary Seton[4] – both ladies-in-waiting to Mary Stuart – but also "a number of professional and amateur assistants"[5] from Mary's servants, as well as equally professional embroiderers and other employees from Bess's servants.[6] The fact that such a large group of embroiderers was needed to realize the ideas of Mary Stuart and Bess of Hardwick is evident from a project carried out by the School of Ancient Crafts from 2014 to 2017: 33 volunteers embroidered 37 pieces of linen according to the original patterns of the so-called Oxburgh Hangings and then assembled them into a tapestry. They used exactly the same materials as in the original and only tools and techniques that were common in the 16th century. It took 7,000 hours of work to produce the replica.[7]

Mary Stuart, Bess of Hardwick, and their teams embroidered in cross-stitch or half-cross-stitch on linen, with the individual pieces of linen embroidered with silk thread in various colors as well as gold and silver thread or gold-plated silver thread, and then sewn onto velvet. Mary Stuart preferred this method because the smaller pieces of work could be done on an embroidery hoop, which could easily be taken from room to room or place to place.[8] Embroidering smaller pieces of linen, which were then later assembled into a hanging, was unknown at the time of Mary Stuart's imprisonment in England, but was common in France and especially at the French court. The method was already in use in the Middle Ages and was revived in the early modern period with the emergence of embroidery on secular and domestic objects.[9] It is possible that the individual pieces were initially intended as pillowcases or bed curtains before being assembled into wall hangings measuring up to 2 x 3 m.[10] The individual embroidered pieces of linen depicted animals and plants, which were combined with inscriptions and symbols. Mary Stuart and Bess of Hardwick marked the pieces they embroidered with a monogram: Mary Stuart combined the letters MA with a Greek Φ superimposed on top, while Bess of Hardwick used the letters ES.[11] Looking at the shape of the pieces of linen and the themes depicted, three categories can be identified: firstly, large squares arranged centrally on the hangings with emblems and a Latin text; secondly, cross-shaped pieces with depictions of animals accompanied by English words and expressions; and thirdly, octagonal pieces with plants and Latin sayings.[12] Choosing different shapes for the appliqué pieces is also a tradition that Mary Stuart brought back from France.[13]

Fig. 1: Monogram of Mary Stuart from the Oxburgh Hangings, inscription with anagram of the French name Marie Stuvarte "sa vertue m'attire".- In: https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/prison-embroideries-mary-queen-of-scots

Fig. 2: Monogram of Bess of Hardwick with the inscription George Elizabeth Shrewesburye.- In: https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/prison-embroideries-mary-queen-of-scots

The templates for the embroidery came from various books on botany and natural history that belonged to Mary Stuart. Among other works, she owned "Devises heroiques" by Claude Paradin, "Le imprese heroiche et morali" by Gabriele Simeoni, "Dialogo dell'imprese" by Paolo Giovio, and "Emblemata" by Hadrianus Junius.[14] She probably also owned "Historia animalium" and "Historia Plantarum" by Conrad Gesner and "De aquatilibus" and other publications by Pierre Belon.[15] Since none of these books were available in English translation, it must be assumed that the highly educated Mary Stuart, whose education at the French court included learning several languages, made a significant contribution to the selection and design of the templates, which also included descriptions of the animals and plants. She had a thorough knowledge of the symbolic language and imagery of her time and was able to use it to give meaning to her embroidery with the help of emblems, so that her embroidery cannot be regarded merely as handicrafts intended to fill her free time.[16]

The fact that Mary Stuart used symbols and metaphors in her embroidery to convey hidden messages clearly shows her resistance to the constant surveillance she was subjected to during her imprisonment. That her contemporaries understood this is proven by the fact that in 1572, an emblem embroidered by Mary Stuart was used as evidence in a trial for conspiracy against Elizabeth I.[17] Here are just a few examples of the political statements made by the embroideries.

The fact that Mary Stuart used symbols and metaphors in her embroidery to convey hidden messages clearly shows her resistance to the constant surveillance she was subjected to during her imprisonment. That her contemporaries understood this is proven by the fact that in 1572, an emblem embroidered by Mary Stuart was used as evidence in a trial for conspiracy against Elizabeth I.[17] Here are just a few examples of the political statements made by the embroideries.

Fig. 3: Thierbuch. Das ist eine kurze beschreybung aller vierfüssigen Thieren, so auff der erden und in wassern wonend, sampt irer waren conterfactur: alles zu nutz von gütern allen liebhabern der künsten, Artzeten, Maleren, Bildschnitzern, Weydleuten und Köchen, gestelt. Erstlich durch den hochgeleerten herren D. Cünrad Geßner in Latin beschriben, yetzunder aber durch D. Cünrad Forer zu mererem nutz aller mennnklichem in das Teutsch gebracht, und in ein kurze kommliche ordnung gezogen. Gedruckt zu Zürych bey Christoffel Froschouwer, im jar als man zalt MDLXXXIII (1583). Single-volume edition of Conrad Gesner's original two-volume "Historiae Animalium" from 1551-1558.- In: digitale-Sammlungen.de

The embroidery used as evidence in the aforementioned trial is the centerpiece of the so-called Oxbourgh Hanging, parts of which Mary Stuart designed together with Bess of Hardwick. The embroidery shows a hand reaching down from the sky, cutting a dry branch from a vine. The motto is "Virescit vulnere virtus"[18] . The depiction has several meanings: on the one hand, it could allude to the fact that Elizabeth I had no descendants, while Mary Stuart had a son, James, born in 1566. Thus, there could be a hidden call here to replace the childless Elizabeth with Mary, who was blessed with a son, and to do so with the express blessing of God, for the hand reaching down from heaven is to be understood as the hand of God, who directs the fate of human beings. Another interpretation is that the tree pruned by God is favored by God both in the afterlife and in the world because it becomes stronger and more vigorous. Applied to the situation, this would mean that Mary, favored by God, is increasingly prepared to take over the reign.[19] Both interpretations can be understood as indirect calls for rebellion, which is why the embroidery was used in the trial against the Duke of Norfolk, whom Mary was considering marrying. Of course, one can also limit oneself to the superficial interpretation, which translates the term virtus as virtue. In that case, the message would be that by renouncing evil and wrongdoing, human virtue is only strengthened, ensuring God's blessing in the hereafter. In view of the multiple political statements made in other parts of the hanging, the latter interpretation can be seen, but it is not the primary intended message.

Fig. 4: Centerpiece of the Oxbourgh Hanging with the inscription „Virescit vulnere virtus“.- In: https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/prison-embroideries-mary-queen-of-scots

Thus, the phoenix in the Oxbourgh Hangings can initially be interpreted simply as a symbol used in memory of Mary Stuart's mother, Mary of Guise , who frequently used this symbol of the bird burning in death and reborn from its ashes.[20] However, the phoenix is also a symbol of immortality, so that Mary is alluding to her Catholic religion on the one hand, but also indirectly threatening that her Catholic allies would regard her as a martyr if anything happened to her, thus ensuring that she herself would remain immortal in their memory. This interpretation corresponds to the motto "En ma Fin gît mon Commencement" (In my end is my beginning), which Mary had embroidered on one of her dresses shortly before her execution.[21]

Fig. 5: Phoenix, section from the Oxbourgh Hanging.- In: https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/prison-embroideries-mary-queen-of-scots

Among the individually preserved embroideries is a cat playing with a mouse. The cat has reddish fur, which can be seen as an allusion to the red-haired Queen Elizabeth I. She is playing with the defenseless gray mouse, which Mary Stuart obviously sees herself as.[22] This is a subtle description of the relationship between the two queens from Mary's point of view: Elizabeth abuses her position as the superior by treating the captive Mary cruelly and arbitrarily.

The depiction of a turtle climbing up the trunk of a crowned palm tree also contains a clear political statement. The motto is "Dat Gloria Vires"[23]. Here, the turtle symbolizes patience, perseverance, and wisdom, while the palm tree represents triumph over sin and death. Thus, this embroidery can be interpreted as the triumph of Mary's patience and perseverance over Elizabeth's sin, which is rewarded by the crown that the turtle ultimately reaches, especially since her honorable behavior gives her strength.

Fig. 7: "Turtle" from the Oxbourgh Hanging.- In: https://www.edinburghcastle.scot/media/1127/mqos-replica-embroideries-leaflet.pdf

The embroideries produced by Mary Stuart, Bess of Hardwick, and their servants were not based solely on patterns and designs chosen by the highly educated Mary Stuart. Despite her upbringing, which was more in line with the principles of the landed gentry, Bess of Hardwick was also "a product of the same Christian humanist culture as many of her elite contemporaries, and it was her sharp intellect [...] that helped her win their praise. "[24] However, Bess only spoke English, so it can be assumed that she acquired most of the necessary knowledge through Mary Stuart's translations.[25] Under Bess of Hardwick's supervision, five large tapestries were made, four of which have survived: Zenobia, Lucretia, Penelope, and Artemis serve as examples of women's ability to take on political and moral leadership roles.[26] Using her knowledge of ancient mythology and history, Bess of Hardwick used these embroideries to participate in the debate of her time on what we would now call women's issues. All of the tapestries are composed according to the same pattern: three figures are placed side by side, separated by Ionic columns. The central figure from mythology or history is depicted in the middle, flanked by two figures, each personifying one of the prominent virtues.[27] It is believed that Bess identified most closely with the depiction of Penelope, who also used a "feminine" craft to make her own decisions about her life.[28] Nobility, bravery, prudence, generosity, chastity, constancy, loyalty, perseverance, and patience are the virtues shown here as role models for women. They are intended to prove that women are indeed capable of successfully working for the good of their families and their country.[29]

Fig. 8: Depiction of Penelope with Constans and Patentia.- In: Remarkable English Renaissance Wall Hangings: "The Noble Women".- In: https://www.theepochtimes.com/bright/remarkable-english-renaissance-wall-hangings-the-noble-women-3687465

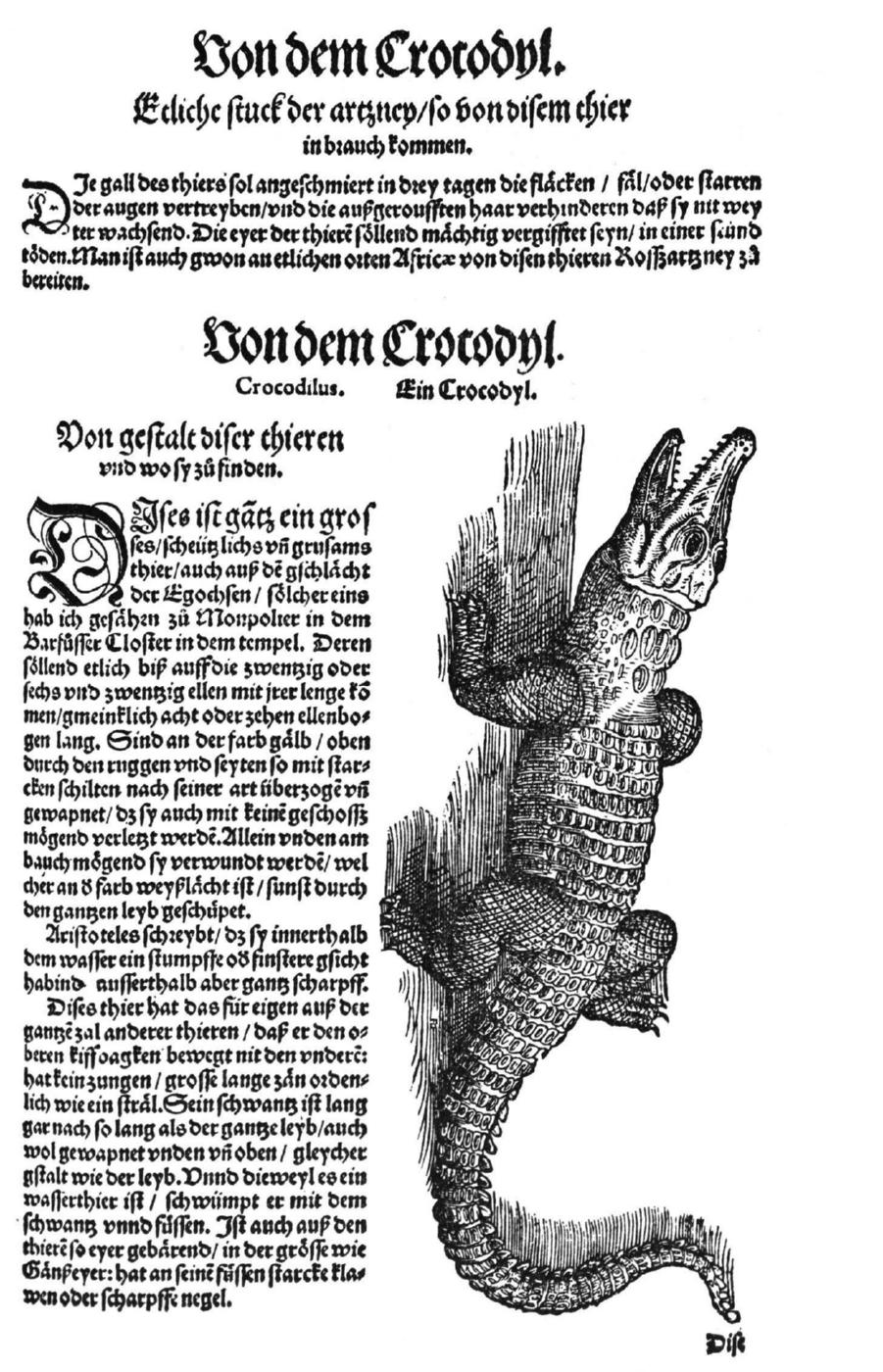

However, the depictions of the embroideries designed by Mary Stuart and Bess of Hardwick, or commissioned by them, belong—at least in part—not only to the context of the conflict between Elizabeth I and Mary Stuart, but also to the spirit of the Renaissance as a whole: intellectual curiosity and a thirst for knowledge characterize this era and are part of the human image of the time. For women in particular, it was important to strike a socially acceptable balance between acquiring knowledge and participating in public discourse on the one hand, and maintaining their role as diligent and pious women focused on the home on the other.[30]The reason for this difficulty was that, based on the biblical story in which Lot's wife disobeys God's command and turns around during their flight to see what is happening to Sodom and Gomorrah, whereupon she is turned into a pillar of salt, thirst for knowledge was equated with curiosity and seen as a specifically female weakness.[31] In contrast, after initial hesitation, thirst for knowledge in men was considered socially acceptable and was one of the characteristics of a male elite.[32] Women found a way out of their dilemma by combining manual labor, which was supposedly character-building and morally desirable, with the acquisition and internalization of knowledge. They used illustrations in predominantly scientific books on the animal and plant world, as well as figures from rediscovered texts by ancient authors, to create embroidery patterns, accompanying the images with a motto and/or text to express complex ideas.[33] In doing so, they not only had to refer to the illustrations in the natural science books, but also had to include the comments in these books and compare them with other sources of this kind in order to achieve an accurate representation. The implementation also required a carefully considered choice of colors and embroidery materials.[34] This work required not only the appropriate resources for the books, but also education and time, and of course the aforementioned interest in scientific knowledge. Mary Stuart's and Bess of Hardwick's embroideries thus reflect contemporary habits regarding scientific collections.[35] At the same time, however, they serve as memory aids, which was extremely important at a time when new discoveries were being made and disseminated in rapid succession and it was therefore important to keep up to date in order to participate in scholarly discourse. They can be seen as the "female" counterparts to the cabinets of curiosities and numerous notebooks of the male world of that time.

Fig. 9: Depiction and description of the crocodile in Conradi Gesneri medici Tigurini historiae animalium liber II.- In: www.e-rara.ch/download/pdf/2344137.pdf

Fig. 10: Crocodile, embroidery from the Shrewsbury Hanging.- In: https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O137617/the-shrewsbury-hanging-hanging-mary-queen-of/?carousel-image=2010EB1722

Fig. 11: Depiction of the crane in Gesner's "Historiae Animalium".- In: www.e-rara.ch/download/pdf/2344137.pdf

Fig. 12: Depiction of the crane in the Shrewsbury Hanging.- In: https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O137617/the-shrewsbury-hanging-hanging-mary-queen-of/?carousel-image=2010EB1713

In summary, it can be said that the embroideries of Mary Stuart and Bess of Hardwick promote participation in the ideological developments of the time, effectively overturning the rules of gender roles in society, and can be seen as an encouragement to other women to break out of the roles imposed on them. The extent to which this was successful is difficult to ascertain, as in most cases it is not known where embroideries of this kind were kept and displayed beyond the circle of women working together, or whether they were confined to non-public areas of a house so as not to endanger a family against politically or religiously oriented opponents.[36] However, it can be assumed that Mary Stuart and Bess of Hardwick considered the message inherent in the embroidery to be very important. Although they had numerous assistants at their disposal, they mainly used cross-stitch, which allowed them to produce many individual pieces in a relatively short time and thus served the purposes of the two ladies.