Cross-Stitch in the Early Modern Period

While cross-stitch appeared only very sparsely as an embroidery technique until the end of the Middle Ages, this obviously changed from the early modern period onwards.

Around 1500, an embroidery was created that was limited exclusively to the cross-stitch technique. It is a front cover, i.e., a decorated strip for the front edge of the altar plate.[1] The pattern uses motifs from folk art: " Lebensbäume mit spiegelbildlich einander sich gleichenden Tieren zu beiden Seiten. "[2] Appuhn suspects that this embroidery was either a gift or simply an experiment by the monastery embroiderers, which they did not repeat because cross-stitch was not suitable for depicting entire groups of figures.[3] The so-called "Philippine-Welser-Decke mit Tiroler Motiven im Kreuzstich"[4] dates from an even later period, but before 1580.

Fig. 1: Cross-stitch embroidery from the Lüne convent, created around 1500 (own photo)

Fig. 2: Motifs from the so-called Philippine Welser Decke, created before 1580, re-embroidered. In: Stradal, Marianne/Brommer, Ulrike: Mit Nadel und Faden. Kulturgeschichte der klassischen Handarbeiten (With Needle and Thread: Cultural History of Classical Handicrafts), Freiburg 1990, p. 59

In general, cross-stitch " [gewann] in der zweiten Hälfte des 16. Jahrhunderts […] mit dem Aufkommen der farbig ausgestickten Kanevasstickereien rasch an Bedeutung und wurde immer hauptsächlicher angewandt."[5], whereas in the first half of the 16th century, embroidery was still predominantly monochrome. This is also evident in the increasing proportion of cross-stitch work and canvas embroidery[6] in the total number of embroideries preserved, not only in absolute terms but also in percentage terms, considering that the density of finds increases with the passage of time[7], although "aus der Fülle der Stickereien, die der Verschönerung häuslicher Textilien dienten, […] entsprechend stärkerer Nutzung nur ein Bruchteil erhalten geblieben ist."[8] In the field of interior design, cushions, bedspreads[9], tablecloths[10], ceremonial towels,[11] embroidered pictures and ornaments,[12] bed curtains,[13] pin cushions,[14] book covers,[15] as well as wall screens and even saddle and pistol bags,[16] and presumably much more besides, were made. Clothing was also embroidered,[17] initially primarily underwear, which was decorated with narrow braids. These fashionable decorations became larger in the 16th century and were applied to other parts of clothing, such as ruffs and ruffles on sleeves.

Fig. 3: Pillowcase, 16th century. Red cross-stitch embroidery on linen background.- In: https://skd-online-collection.skd.museum/Details/Index/255669

Fig. 4: White knitted gloves made of linen with red cross-stitch embroidery in silk, 16th century.

Fig. 5: Bag, first half of the 17th century, embroidery with cross stitch, braid stitch and petit point stitch on linen.- In: https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O78799/purse-unknown/

Fig. 6: Men's shirt, around 1540. Blue cross-stitch embroidery on fine linen on the collar and cuffs, i.e. the parts of the shirt that were visible. - In: https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O115767/shirt-unknown/

Several factors are likely to have contributed to the wider spread of "nun modischen Kanevasstickereien aus Kreuz- und Perlstichen"[18] since the early modern period.

On the one hand, cross-stitch is regarded as an embroidery technique that can be carried out on undemanding material[19] that is easy to obtain. Counted cross-stitch is quick to learn, and the repetition of the same stitch and pattern means that ornaments can be produced in a very short time and the embroidery ground can be embroidered much faster than the finer, more laborious techniques of needle painting,[20] which is why a distinction is made in English between embroidery and needlepoint or needlework: embroidery refers to needle painting and needlepoint to canvas embroidery.

The question is, of course, to what extent and why there was a need for simpler work and faster completion. The reason may be that in the early modern period, as mentioned above, embroidered bridal trousseaus became fashionable and, in addition to the abundance of potentially objects intended for embroidery, attempts were now also made to achieve the appearance of knitted tapestries by means of cross-stitch work covering the entire surface.[21] If such work had been commissioned from a guild master who would have used more complicated embroidery techniques of needle painting, the work would probably have been very expensive and would have taken a long time to complete, which would have been acceptable for embroidery intended for church purposes, but not for embroidery intended for domestic use. It can therefore be assumed that in the early modern period, cross-stitch work was produced in the home, so that "sich von nun an in erster Linie auch breitere Schichten von Laien und Amateuren damit [beschäftigten].“[22] Embroidery was not only found in bourgeois households, but also "auch in den textilen Gegenständen des Alltags und der Kleidung des einfachen Volkes"[23] For this reason, Stradal and Brommer refer to the early modern period as the "Geburtsstunde unserer volkstümlichen"[24], which had already begun with the development of white embroidery in the 12th century.[25]

On the one hand, cross-stitch is regarded as an embroidery technique that can be carried out on undemanding material[19] that is easy to obtain. Counted cross-stitch is quick to learn, and the repetition of the same stitch and pattern means that ornaments can be produced in a very short time and the embroidery ground can be embroidered much faster than the finer, more laborious techniques of needle painting,[20] which is why a distinction is made in English between embroidery and needlepoint or needlework: embroidery refers to needle painting and needlepoint to canvas embroidery.

The question is, of course, to what extent and why there was a need for simpler work and faster completion. The reason may be that in the early modern period, as mentioned above, embroidered bridal trousseaus became fashionable and, in addition to the abundance of potentially objects intended for embroidery, attempts were now also made to achieve the appearance of knitted tapestries by means of cross-stitch work covering the entire surface.[21] If such work had been commissioned from a guild master who would have used more complicated embroidery techniques of needle painting, the work would probably have been very expensive and would have taken a long time to complete, which would have been acceptable for embroidery intended for church purposes, but not for embroidery intended for domestic use. It can therefore be assumed that in the early modern period, cross-stitch work was produced in the home, so that "sich von nun an in erster Linie auch breitere Schichten von Laien und Amateuren damit [beschäftigten].“[22] Embroidery was not only found in bourgeois households, but also "auch in den textilen Gegenständen des Alltags und der Kleidung des einfachen Volkes"[23] For this reason, Stradal and Brommer refer to the early modern period as the "Geburtsstunde unserer volkstümlichen"[24], which had already begun with the development of white embroidery in the 12th century.[25]

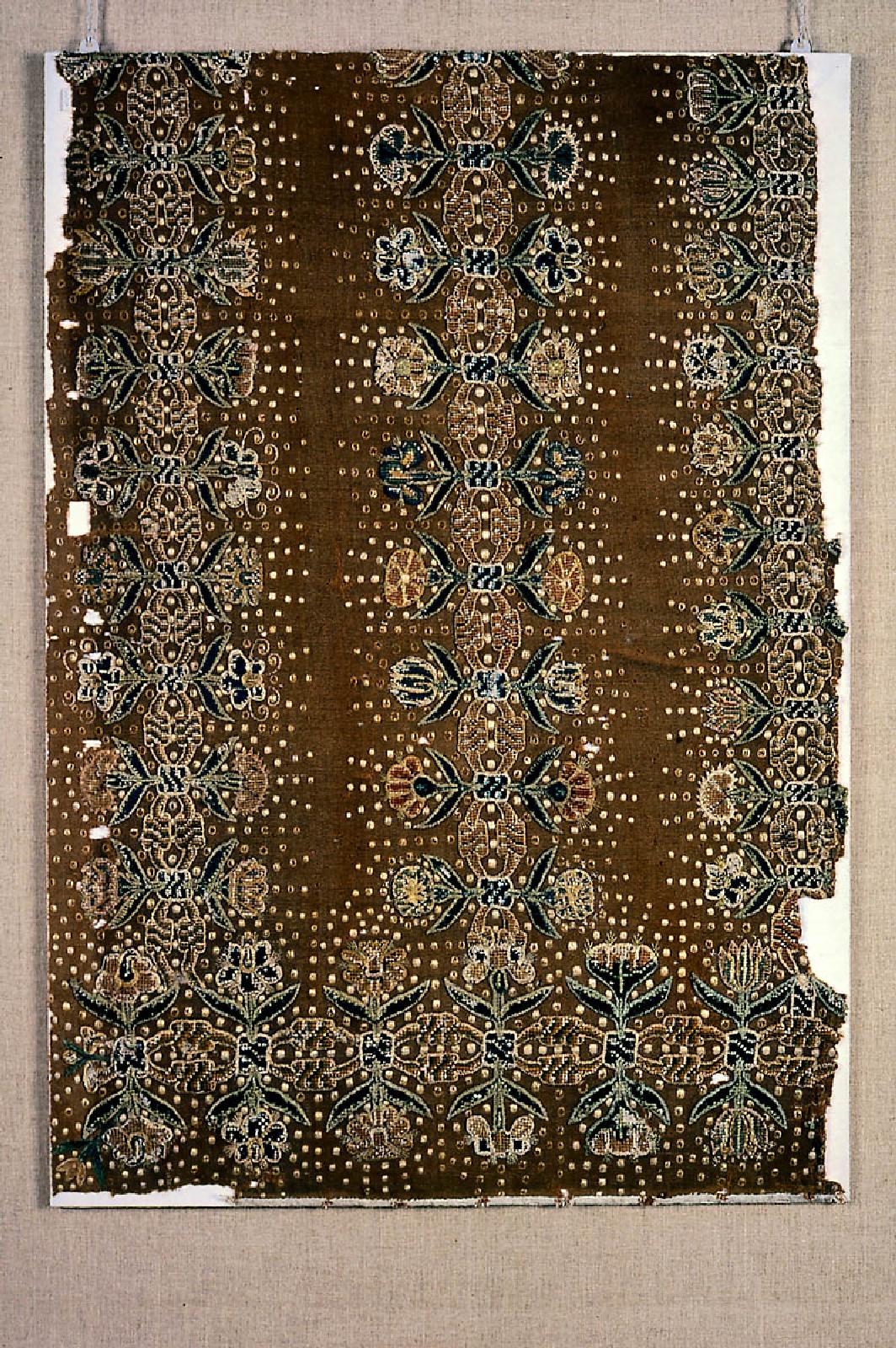

Fig. 7: Wall hanging or bed curtain (fragment), 16th century, cross-stitch embroidery on linen. - Bergemann, Uta-Christiane: Europäische Stickereien 1250-1650 (European Embroidery 1250-1650), 1st edition. Regensburg 2010 (= Catalogs of the German Textile Museum Krefeld Vol. 3), p. 82

It seems that this development was accompanied by a very significant change in the role of women and the way women were viewed.

This is particularly evident in the position of women in commercial life. The agricultural "revolution" in the High Middle Ages and the resulting population growth were reflected both in the extensification of agriculture and in the wave of city foundations in the 12th and 13th centuries, as agriculture was able to feed the growing population at relatively stable prices. The so-called "Little Ice Age," which began in the second half of the 13th century, led to overproduction of agricultural products in the 14th century, despite considerable population losses due to crop failures, famines, and the plague, and thus to a decline in prices. In the cities, at least in the larger ones, prices for handcrafted products rose, favored by increased demand due to the concentration of wealth among the survivors of the plague and a change in the market situation brought about by the onset of early capitalism. Roughly speaking, an economy based on meeting demand became an economy based on creating demand, which extended particularly to luxury goods, which undoubtedly included embroidery. The new market situation was accompanied by a change in quality requirements, which led to increasing specialization and professionalization in the skilled trades. In the field of embroidery, there had already been a differentiation between coat of arms embroiderers and silk embroiderers since the emergence of the guilds; now, however, formal qualifications were emphasized much more strongly, as they were seen as proof of product quality. The rising prices for handcrafted products were correspondingly attractive to male master craftsmen, who – with the exception of Cologne, which occupies a special position – gradually succeeded in displacing women from the guilds and thus from professional embroidery. Felleckner states that women "ab Mitte des 16. Jahrhunderts systematisch von ihren männlichen Kollegen aus den Zünften und damit aus dem Handwerk gedrängt [wurden]"[26] by no longer teaching the daughters of craftsmen the craft and by depriving the widows of craftsmen of the right to continue production undiminished and to train apprentices.[27] This process was supported by the journeymen's guilds, which had also emerged as a result of rural exodus in the wake of the agricultural crisis and which campaigned for a ban on women's work in order to improve the journeymen's chances of becoming master craftsmen.[28] They used a moral argument, citing the potential violation of their honor that could arise from unmarried women and men working and living together.[29] Michael reports that as early as 15th-century England, "more and more men are recorded as embroiderers,"[30] and Heimgärtner reports that in Switzerland, "das Sticken als Beruf [sei] bis in die Neuzeit hinein eine Männerdomäne [gewesen."[31] For England, Clare Hunter points out that male embroiderers secured the lucrative commissions, thus relegating female embroiderers to commissions that required fewer skills. The loss of status for women ultimately led to women no longer having access to professional training. Their embroidery was considered amateurish and unprofessional.[32] The allegedly unskilled work of women was accordingly devalued as "botched." [33]

This is particularly evident in the position of women in commercial life. The agricultural "revolution" in the High Middle Ages and the resulting population growth were reflected both in the extensification of agriculture and in the wave of city foundations in the 12th and 13th centuries, as agriculture was able to feed the growing population at relatively stable prices. The so-called "Little Ice Age," which began in the second half of the 13th century, led to overproduction of agricultural products in the 14th century, despite considerable population losses due to crop failures, famines, and the plague, and thus to a decline in prices. In the cities, at least in the larger ones, prices for handcrafted products rose, favored by increased demand due to the concentration of wealth among the survivors of the plague and a change in the market situation brought about by the onset of early capitalism. Roughly speaking, an economy based on meeting demand became an economy based on creating demand, which extended particularly to luxury goods, which undoubtedly included embroidery. The new market situation was accompanied by a change in quality requirements, which led to increasing specialization and professionalization in the skilled trades. In the field of embroidery, there had already been a differentiation between coat of arms embroiderers and silk embroiderers since the emergence of the guilds; now, however, formal qualifications were emphasized much more strongly, as they were seen as proof of product quality. The rising prices for handcrafted products were correspondingly attractive to male master craftsmen, who – with the exception of Cologne, which occupies a special position – gradually succeeded in displacing women from the guilds and thus from professional embroidery. Felleckner states that women "ab Mitte des 16. Jahrhunderts systematisch von ihren männlichen Kollegen aus den Zünften und damit aus dem Handwerk gedrängt [wurden]"[26] by no longer teaching the daughters of craftsmen the craft and by depriving the widows of craftsmen of the right to continue production undiminished and to train apprentices.[27] This process was supported by the journeymen's guilds, which had also emerged as a result of rural exodus in the wake of the agricultural crisis and which campaigned for a ban on women's work in order to improve the journeymen's chances of becoming master craftsmen.[28] They used a moral argument, citing the potential violation of their honor that could arise from unmarried women and men working and living together.[29] Michael reports that as early as 15th-century England, "more and more men are recorded as embroiderers,"[30] and Heimgärtner reports that in Switzerland, "das Sticken als Beruf [sei] bis in die Neuzeit hinein eine Männerdomäne [gewesen."[31] For England, Clare Hunter points out that male embroiderers secured the lucrative commissions, thus relegating female embroiderers to commissions that required fewer skills. The loss of status for women ultimately led to women no longer having access to professional training. Their embroidery was considered amateurish and unprofessional.[32] The allegedly unskilled work of women was accordingly devalued as "botched." [33]

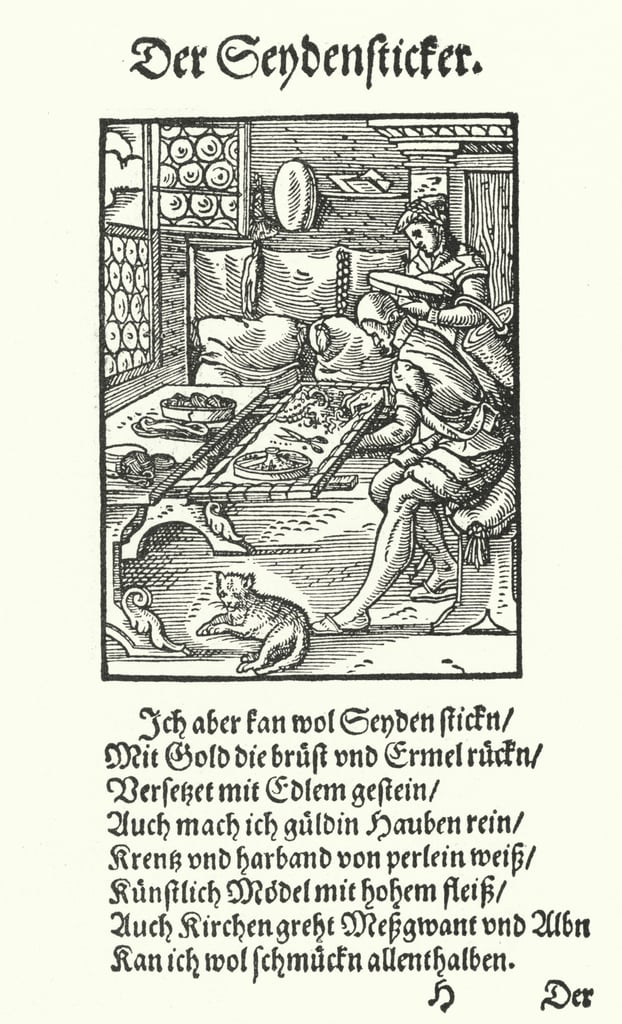

Fig. 8: The silk embroiderer from Jost Amman's book of guilds, 1568.- In: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/

File:Acupictor._Der_Seidensticker._

(The_Embroiderer)_

(BM_1904,0206.103.27).jpg

Text von Hans Sachs:

Ich aber kan wol Seyden stickn/

Mit Gold die brüst und Ermel rückn/

Versetzet mit Edlem gestein/

Auch mach ich güldin Hauben rein/

Krentz und harband von perlein weiß/

Künstlich Mödel mit hohem fleiß/

Auch Kirchen greht Meßgwant und Albn

Kan ich wol schmückn allenthalben

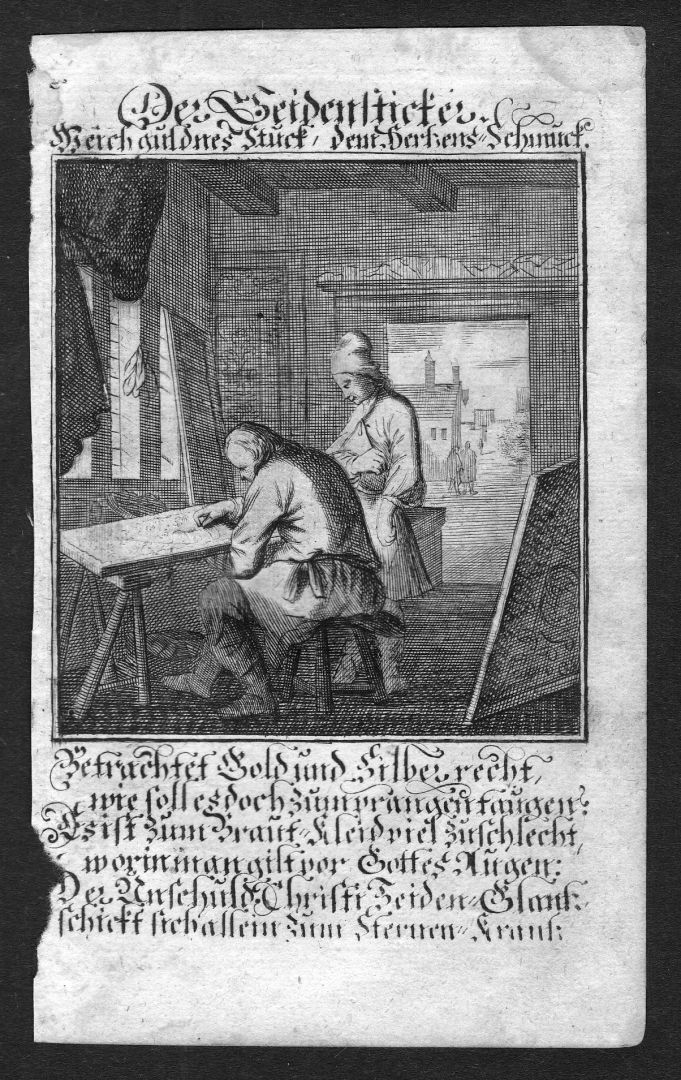

Fig. 9: The silk embroiderer. Engraving from Christoph Weigel's "Abbildungen der Gemein-Nützlichen Hauptstände", 1698.- In: https://digital.slub-dresden.de/werkansicht/dlf/88/

53?tx_dlf_navigation%5Bcontroller%5D

=Navigation&cHash=2b7eef6229ba85ff2

b6ec7ffb9f4c277

Text von Abraham a Santa Clara:

Betrachtet Gold und Silber recht/

Wie soll es doch zum prangen taugen?

Es ist zum Braut-Kleid viel zu schlecht,

Worin man gilt vor Gottes Augen:

Der Unschuld Christi Seiden- Glantz

Schickt sich allein zum Sternen-Kranz.

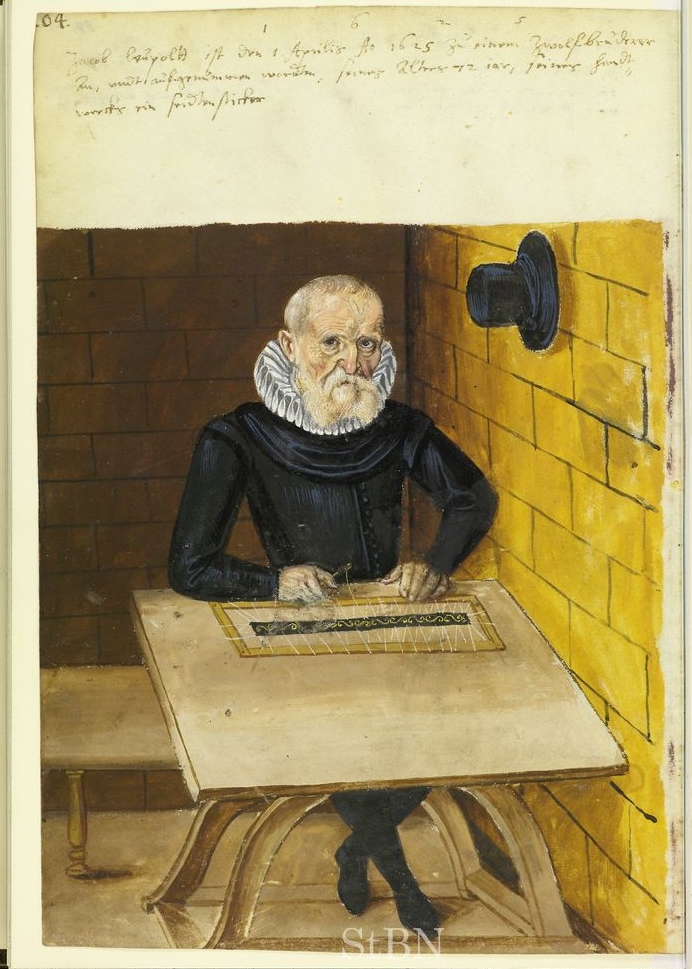

Fig. 10: Portrait of the silk embroiderer Jakob Leupoltt from the Nuremberg house books, 1625.- In:

Jakob Leupoltt Nürnberger Hausbücher - Google Suche

Jakob Leupoltt Nürnberger Hausbücher - Google Suche

Of course, this development took place slowly and varied from region to region[34], and there were also trades in which women continued to work independently. An example of the latter is Cologne, where silk embroiderers remained a female guild, but where women also continued to work in various crafts in general.[35] In England and Scotland, too, there were still women who were self-employed in various trades.[36] As time went on, in addition to the women who continued to be organized in guilds in the cities, there were also court embroiderers[37] and embroiderers who worked in manufactories from the 17th century onwards as part of the mercantilist economy of the absolutist states. However, the general trend was that women no longer embroidered professionally, but were relegated to embroidery for use in their own homes, resulting in a preference for cross-stitch as an embroidery technique that did not require specialized training.

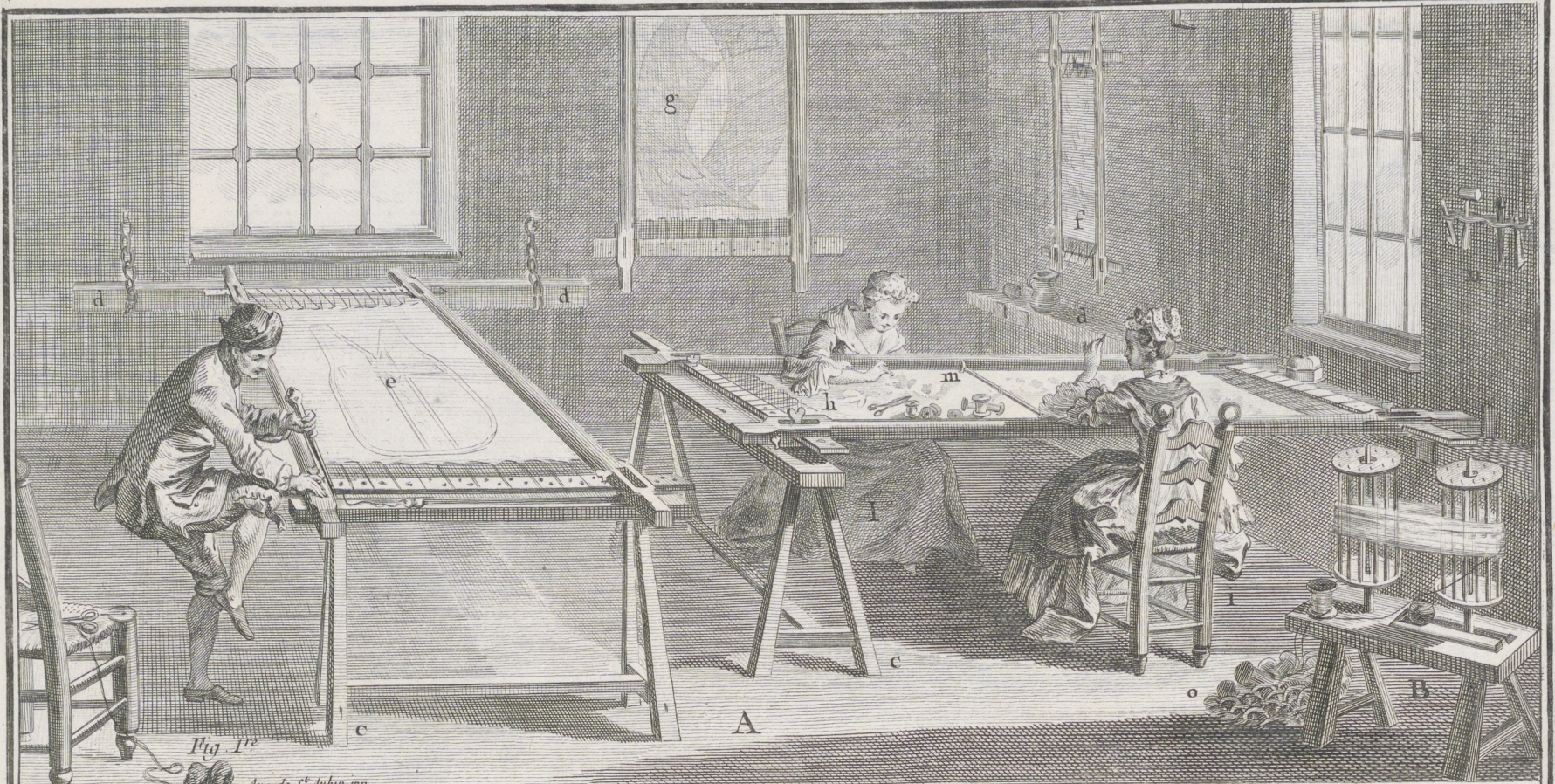

Fig. 11: Workshop of court embroiderers, Charles-Germain de Saint-Aubin, L'Art du Brodeur, 1770. Saint-Aubin was court embroiderer at the court of Louis XIV. - In: https://voltairefoundation.wordpress.com/tag/lart-du-brodeur/

Support for the aforementioned change in the commercial sector came from the ethics of the Reformation and humanism, which emphasized the importance of leading a respectable life and created new standards for the education of girls, which were to be used as a guide for reality.[38] Respectability and chastity were the highest educational goals, with all other skills taking a back seat. Education was considered undesirable, as "jedwede Intellektualität sofort mit sexueller Ausschweifung gleichgesetzt [wurde]."[39] The only norm for women's lifestyles was the institution of marriage, which was now regarded as the "Modellfall der Geschlechterordnung."[40] This relegated women to the role of wife and housewife in a patriarchal relationship.[41]

In Germany and many other European countries in the 16th and 17th centuries, this new standard was reflected in what is known as "Hausväterliteratur", which today would belong to the genre of self-help literature. It not only conveyed a moral code in line with the aforementioned basic attitude, but also contained very specific advice and instructions for running a household. It was based on the idea of the "whole house" as a "hierarchisch gegliederte[r] Gemeinschaft von Hausvater, Hausmutter, Kindern und Gesinde […] Ziel der Hausgemeinschaft war eine statusgemäße Versorgung aller Mitglieder, die Besitzerhaltung und -vergrößerung und das Aufziehen von Kindern und Enkeln."[42] It thus follows in the tradition of the purpose-oriented community of the patriarchal association under the authority of the master of the house, consisting of the master, the housewife, unmarried children, and servants, as was customary in the Middle Ages. The concept of the "whole house" saw the role of the wife, i.e., the house mother, as twofold: on the one hand, she was not an equal partner to the head of the household, but rather "Gehilfin ihres Mannes“[43] who was incapable of running a household on her own; on the other hand, she exercised authority because she "genauso wie ihr Mann zum gemeinsamen Vermögen bei[trägt], und das kann nur wachsen, wenn sie als Betriebsleiterin die absolute Kontrolle über Ausgaben, Personal und Arbeitsabläufe ausübt."[44] Since the early modern period, a woman's work was thus no longer determined by her social status, but by her gender. The woman was not only the educator of the children, but she also managed the interior of the house by planning, distributing to the servants, and supervising the work in the house[45] – which also included work directly supporting the household, such as tending the garden or caring for the livestock, as well as marketing the surplus production from these areas, etc. She had to have a thorough command of practically all areas of housekeeping in order to avoid being deceived by her staff. She also had the right to hire or dismiss staff, as well as to incur expenses and generate income from the sale of surplus products. In addition to all her managerial duties, it is conceivable that the housekeeper performed some tasks herself, such as bookkeeping, but also work that could only be done by hands that were not rough or calloused from labor. This certainly included sewing linen and clothing, and in wealthy households probably also embroidering linen and clothing and embroidering interior furnishings, even if we can only guess " wie weit die Kenntnis und Praxis des Stickens auch in einfachen Bevölkerungsschichten geläufig war."[46].

In Germany and many other European countries in the 16th and 17th centuries, this new standard was reflected in what is known as "Hausväterliteratur", which today would belong to the genre of self-help literature. It not only conveyed a moral code in line with the aforementioned basic attitude, but also contained very specific advice and instructions for running a household. It was based on the idea of the "whole house" as a "hierarchisch gegliederte[r] Gemeinschaft von Hausvater, Hausmutter, Kindern und Gesinde […] Ziel der Hausgemeinschaft war eine statusgemäße Versorgung aller Mitglieder, die Besitzerhaltung und -vergrößerung und das Aufziehen von Kindern und Enkeln."[42] It thus follows in the tradition of the purpose-oriented community of the patriarchal association under the authority of the master of the house, consisting of the master, the housewife, unmarried children, and servants, as was customary in the Middle Ages. The concept of the "whole house" saw the role of the wife, i.e., the house mother, as twofold: on the one hand, she was not an equal partner to the head of the household, but rather "Gehilfin ihres Mannes“[43] who was incapable of running a household on her own; on the other hand, she exercised authority because she "genauso wie ihr Mann zum gemeinsamen Vermögen bei[trägt], und das kann nur wachsen, wenn sie als Betriebsleiterin die absolute Kontrolle über Ausgaben, Personal und Arbeitsabläufe ausübt."[44] Since the early modern period, a woman's work was thus no longer determined by her social status, but by her gender. The woman was not only the educator of the children, but she also managed the interior of the house by planning, distributing to the servants, and supervising the work in the house[45] – which also included work directly supporting the household, such as tending the garden or caring for the livestock, as well as marketing the surplus production from these areas, etc. She had to have a thorough command of practically all areas of housekeeping in order to avoid being deceived by her staff. She also had the right to hire or dismiss staff, as well as to incur expenses and generate income from the sale of surplus products. In addition to all her managerial duties, it is conceivable that the housekeeper performed some tasks herself, such as bookkeeping, but also work that could only be done by hands that were not rough or calloused from labor. This certainly included sewing linen and clothing, and in wealthy households probably also embroidering linen and clothing and embroidering interior furnishings, even if we can only guess " wie weit die Kenntnis und Praxis des Stickens auch in einfachen Bevölkerungsschichten geläufig war."[46].

Fig. 12: The "Whole House." Ceiling depicting rural and domestic activities, around 1600.- In: LM-22202-0-Leinenstickerei.pdf

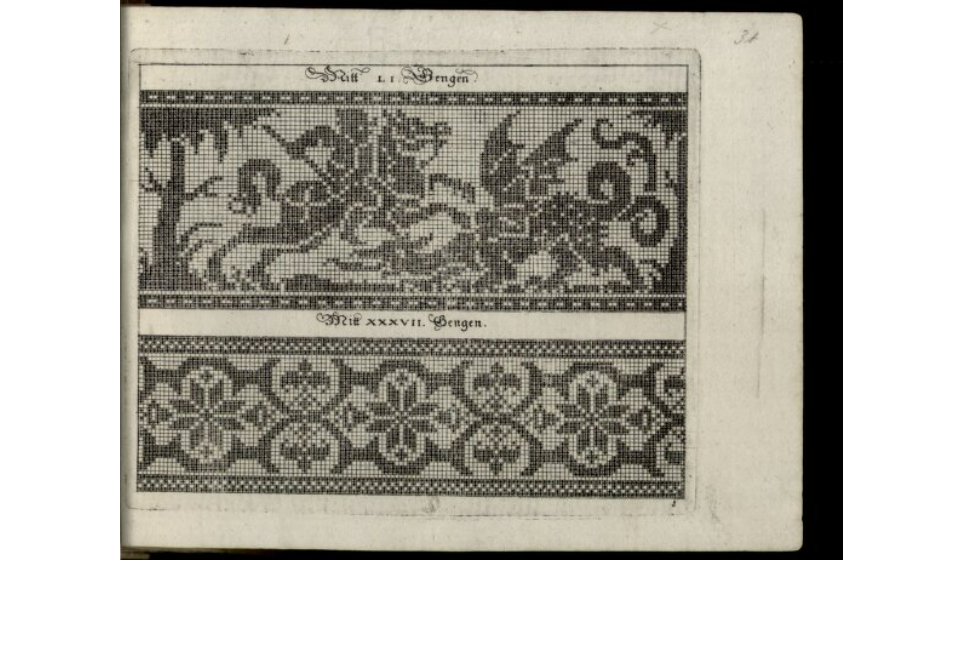

Another factor in the increase in domestic, non-professional canvas embroidery, which was predominantly done in cross-stitch,[47] is certainly the emergence of so-called pattern or template books, which were primarily aimed at "common people."[48] They enabled "amateurs," who had to manage without a professional pattern designer, to embroider using counted patterns. The pattern books, which were initially printed in woodcut, used a grid system to enable counted cross-stitch.[49] They often also contained blank pages with a grid so that people could draw their own designs.[50] While the first pattern books were still printed in black and white, leaving the choice of colors up to the embroiderers, multicolor prints appeared as early as the second half of the 16th century. As a further simplification, the colors were indicated by different symbols in the grids,[51] giving the patterns the character of today's embroidery patterns. A further improvement came with copperplate printing, which produced a cleaner image and was therefore easier to read. The patterns contained in the books included braids with predominantly geometric patterns, flowers, animals, and figures.

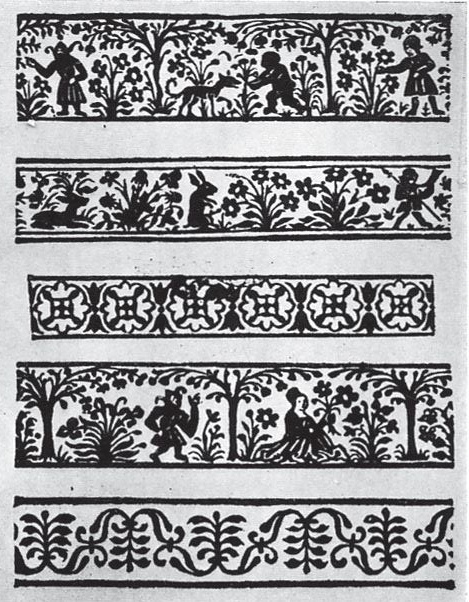

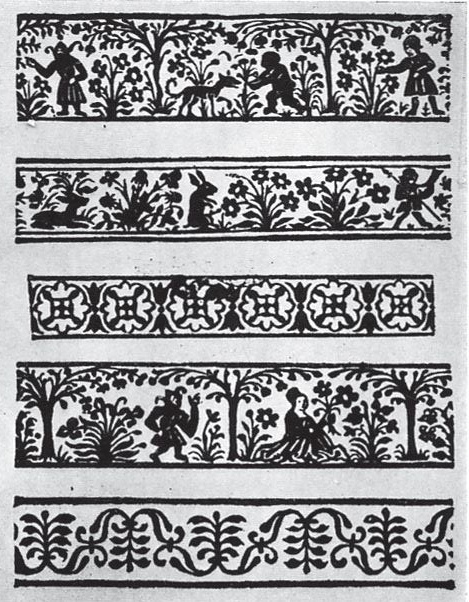

Fig. 13: Patterns from the Furm or Model Booklet (Schönsperger, 1523). In:

Margaret Harrington Daniels, Early Pattern Books for Lace and Embroidery, Part I, no place, no date, p. 2

Margaret Harrington Daniels, Early Pattern Books for Lace and Embroidery, Part I, no place, no date, p. 2

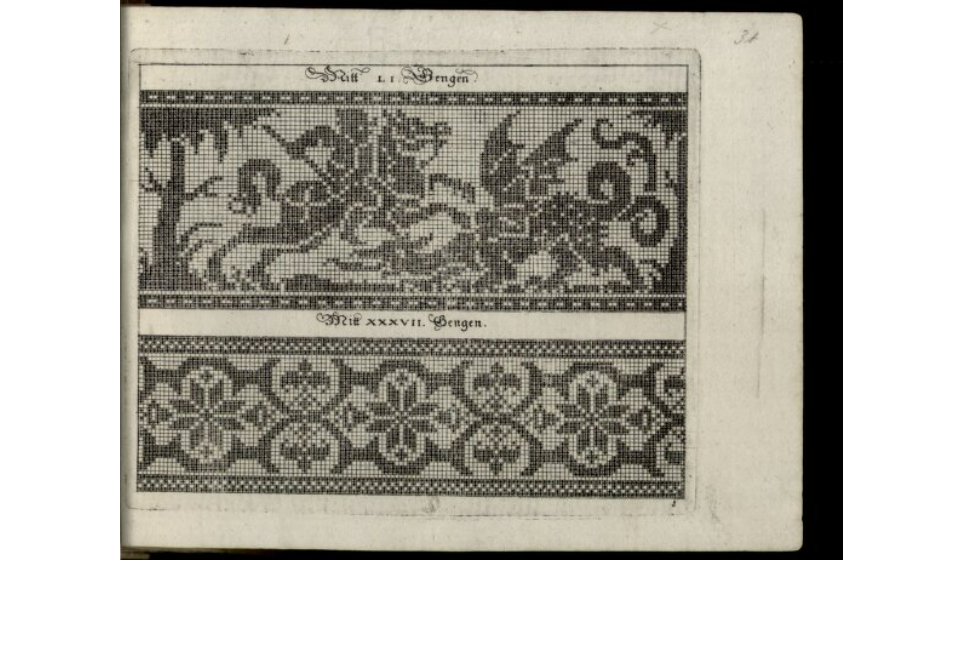

Fig. 14: Patterns from Schön Neues Modelbuch (Sibmacher, 1604).- In: https://www.digitale-sammlungen.de/en/view/bsb00026001?page=63

Note: The illustrations from pattern books mentioned in the footnotes can be found on the following page in order to reduce the loading time of this page.

The first pattern book ever, Hans Schönsperger's "Furm- oder Modelbüchlein", was published in Augsburg in 1523. It appears to have been so successful that just one year later, in 1524, Schönsperger published "Ein New Modelbuch". From 1527 onwards, pattern books by Peter Quentel appeared in quick succession in 1527, 1529, 1532, 1541, and 1544. From then on, this genre seems to have become increasingly popular , so that "between 1523 and 1700, over 150 individual titles were published in an estimated 400 editions, with unknown numbers of print runs."[52] German publishers seem to have dominated the market at first; their success led, at a time when there was no copyright and early capitalist behavior patterns were emerging, to the adoption or variation of designs by publishers from Germany and abroad, in addition to their own new creations, so that ultimately the patterns were in international use, which Sigismund Latomus explicitly used as "advertising" in his "Schön newes Modelbuch", published in 1622, when he spoke of "so wol Italiänischen, Französischen, Niderländischen, Engelländischen, als Teutschen Mödeln.“[53]

Even though the print runs of the books are unknown, the success of the pattern books is undeniable, if only because new pattern books kept coming onto the market. This means that there must have been a corresponding demand for embroidery instructions. As mentioned above, the primary target audience for the pattern books were women and girls[54] from social classes below the "very wealthy" and who, from today's perspective, would be described as middle class. In any case, the target audience had to be able to read and do arithmetic, as well as afford the pattern books. This allows us to identify this middle class more precisely as the (married) wives of merchants and craftsmen, as well as the farm managers described in more detail above, who had servants and not just a maid or a farmhand. Within this circle, there must have been a great many women who embroidered, and it is quite likely that the availability of pattern books increased the number of women who embroidered, which in turn increased demand.

The title pages or frontispieces may provide more information about the target audience and their motives, as they were probably designed to appeal to the intended clientele. Especially in the first half of the 16th century, both the illustrations and the titles of the pattern books emphasize the handicrafts for which the patterns can be used, as well as the learning effect achieved by using the patterns.[55] The illustrations show the various handicrafts or crafts for which the patterns in the book can be used. This makes sense insofar as pattern books were a new genre at that time and potential customers could see at a glance whether the book promised to be suitable for their preferred activity. It also seems that professional and male customers were to be targeted during this period, as both the illustrations and the title text refer to "male" activities.[56] The mention of activities such as stonemasonry and woodcarving may be due to the fact that the first half of the 16th century was a period of upheaval in which the processes described above, namely the displacement of women from the trades and the spread of new role norms, had not yet fully taken hold.

Since the second half of the 16th century, the title illustrations have predominantly shown several women embroidering or doing other needlework together, while – in some cases – the man watches[57] and presumably evaluates the work in terms of quality and aesthetic appeal, which is likely to be linked to an evaluation of the embroidering woman as a wife. The clothing worn by the women in the title illustration of Gulfferich's and Jobin's book is likely to be characteristic of the middle class; it is neither poor nor extravagant. However, as time progresses, the clothing of the women depicted becomes more elaborate, and the scenery also becomes increasingly elegant. What in Gulfferich's 1532 model book still looked like a group of women embroidering or doing needlework in simple clothing in the countryside, by the time of Sibmacher's "Schön Neues Modelbuch" in 1597 and Bretschneider's "New Modelbüch“ in 1615, it has become a group of fashionably and elaborately dressed women embroidering in a spacious room, or a title illustration that appears to show embroidery patterns reminiscent of the luxury goods commonly found at court. The title pages of Rosina Helena Fürst's model books already show clear signs of the opulent fashion and interior design of the early Baroque period.

One could conclude from this that the target audience of model books had changed and that instead of middle-class women, upper-class women were now to be addressed. However, if one looks at the titles of the pattern books, it is clear that the target audience remained middle-class women – from the outset, the books consistently addressed women and young girls who, unlike the noble and wealthy ladies, did not have their own designers and thus belonged to the middle class. The question also arises as to whether ladies from the nobility or the very wealthy circles would have embroidered "Muster artiger Züege, Und Schöner Blummen Zu zierlichen Überschlegen, Haupt- Schürtz- Schnüp Tüchern, Hauben, Handschühen, Mehren gehengen, Kampfüttern und der gleichen"[58] or "Arbeit auff Krägen, Hempter, Facelet und dergleichen"[59] according to a pattern book, or whether they had them designed instead. Rather, it seems that initially the pattern books had in mind the standards set for women by domestic literature when they stated that embroidery had to be learned and practiced according to instructions. The first pattern books enabled women, who were now confined to the home, to embellish the clothing of family members with embroidery and to decorate the rooms in which the family lived with embroidered objects. In this way, they fulfilled their role of contributing to the prosperity of the household through the number of embroidered objects they produced.[60] The titles of the pattern books also support this assumption, as they emphasize virtues that were also set as the norm for women in household literature. Sibmacher addresses "Erbarn Tugendsamen Frawen und Jungfrawen"[61] and, in the 1604 edition, precedes the patterns with a "Dialogus Oder Gespräch dreyer Personen, die Nähkunst betreffend. Namen der Personen in diesem Gespräch. Industria die Arbeitsame, oder Geschickligkeit, Ignavia die Faule, oder Müssiggang, Sophia die Kluge, oder Weißheit"[62] . Latomus focuses on an idyllic scene of women embroidering – and a man busy sketching – in the title illustration of his 1608 pattern book. This is framed by a snake alluding to the story of the expulsion from paradise and by two female figures, one of whom is preoccupied with her mirror image and the other holding a falcon. The embroidering women symbolize the virtues of restless diligence and the industrious pursuit of prosperity, which contrast with the seduction of vanity and (noble) idleness.[63] Rosina Helena Fürst makes it even more explicit in the title image of the third part of her model book in 1666, showing that embroidery and needlework in general make a decisive contribution to the virtue and respectability of women: the divine eye looks favorably upon the woman doing needlework, for "Der Arbeit nutz ist Gottes Schutz," while "Die faule Hand bringt Spott und Schand In Satanshand."[64] This already shows the further change in the role of women that began in the 17th century, with a more pronounced moralization, which will be discussed in more detail below.

Van den Berghe interprets the increasingly prominent depiction of fashionably and elaborately dressed women in the title illustrations from the second half of the 16th century onwards as a marketing strategy that promised middle-class women that by using the patterns in the model book, they could imitate the more elaborate fashion of the upper classes, i.e., a certain lifestyle was promised.[65] For the middle class, which sought social advancement through the consolidation of its wealth, it may well have been attractive to display its prosperity to the outside world through elaborately embroidered clothing and interior furnishings featuring numerous embroideries. Van den Berghe also points out that embroidered gifts – presumably handkerchiefs, small covered boxes, hand mirrors, and the like – could serve to establish and strengthen social relationships, especially since such items were of considerable value before the age of industrialization.[66]

In summary, it can be said that in the early modern period, the suppression of women from trade and their relegation to the domestic sphere initiated a development that led to more women than before taking up embroidery and using the "easier" cross-stitch technique. This development was promoted by the boom in pattern books, the number of which is in turn an indication of the increase in embroidery, especially cross-stitch work, with the growing connotation of embroidery and virtue being an important contributing factor.