Embroidery in the Early Middle Ages

The number of textile finds decorated with embroidery increases in the early Middle Ages. This may, of course, be due to the fact that more finds exist for this period than for the previous one, especially since written sources and other remains provide clues as to where archaeological excavations might be worthwhile. Another reason could be that, for various reasons, the decoration of clothing and other objects gained prestige and became fashionable.

Textile finds dated to around 580 in grave 58 of the Trossingen burial ground show fragments of thread on the base fabric that are classified as decorative embroidery[1]. The literature also mentions embroidery "aus dem in das frühe 7. Jahrhundert datierenden Männergrab 923 des Reihengräberfeldes von Altenerding (Lkr. Erding), ein von Lise Bender-Jørgensen erfasstes Gewebe aus Lembeck (Lkr. Recklinghausen) sowie ein noch unveröffentlichtes, ebenfalls aus einem Männergrab des 7. Jahrhunderts geborgenes Textil der frühmittelalterlichen Nekropole von Aalen-Unterkochen"[2]. The discovery of gold embroidery on silk in the princely tomb of Planig, which dates back to the first third of the 6th century, seems to confirm "die Angaben über die Kleiderpracht des merowingischen Hofes in der Vita des hl. Eligius."[3]. The geographical location of the finds shows that embroidering textiles was by no means a regionally limited custom, but rather a widespread phenomenon, at least among the nobility, which had existed since at least the 6th century.

Fig. 1: Gold-thread embroidered braids from the sleeves of Arnegunde's cloak dress (Musée d'Archéologie nationale de Saint-Germain-en-Laye).- In: Périn, Patrick u.a.: Die Bestattung in Sarkophag 49unter der Basilika von Saint-Denis.- In: Wamers, Egon/Périn, Patrick: Königinnen der Merowinger. Adelsgräber aus den Kirchen von Köln, Saint-Denis,

Chelles und Frankfurt am Main, Regensburg 2012, S. 113

Chelles und Frankfurt am Main, Regensburg 2012, S. 113

The tomb of Arnegunde, wife of the Merovingian king Clothar I. (*around 495, +561), is dated between 571 and 600, i.e. the last third of the 6th century[4]. It is located under the Basilica of Saint-Denis north of Paris. In addition to numerous decorative objects made of gold, silver, and precious stones, a number of textile finds were also made during the excavations. Gold embroidery is found on "einem Mantel aus braunroter, leinengefütterter Seide, der offensichtlich lange, weite Ärmel mit goldbestickten Manschetten besaß."[5] The embroidery is worked in appliqué technique.[6]

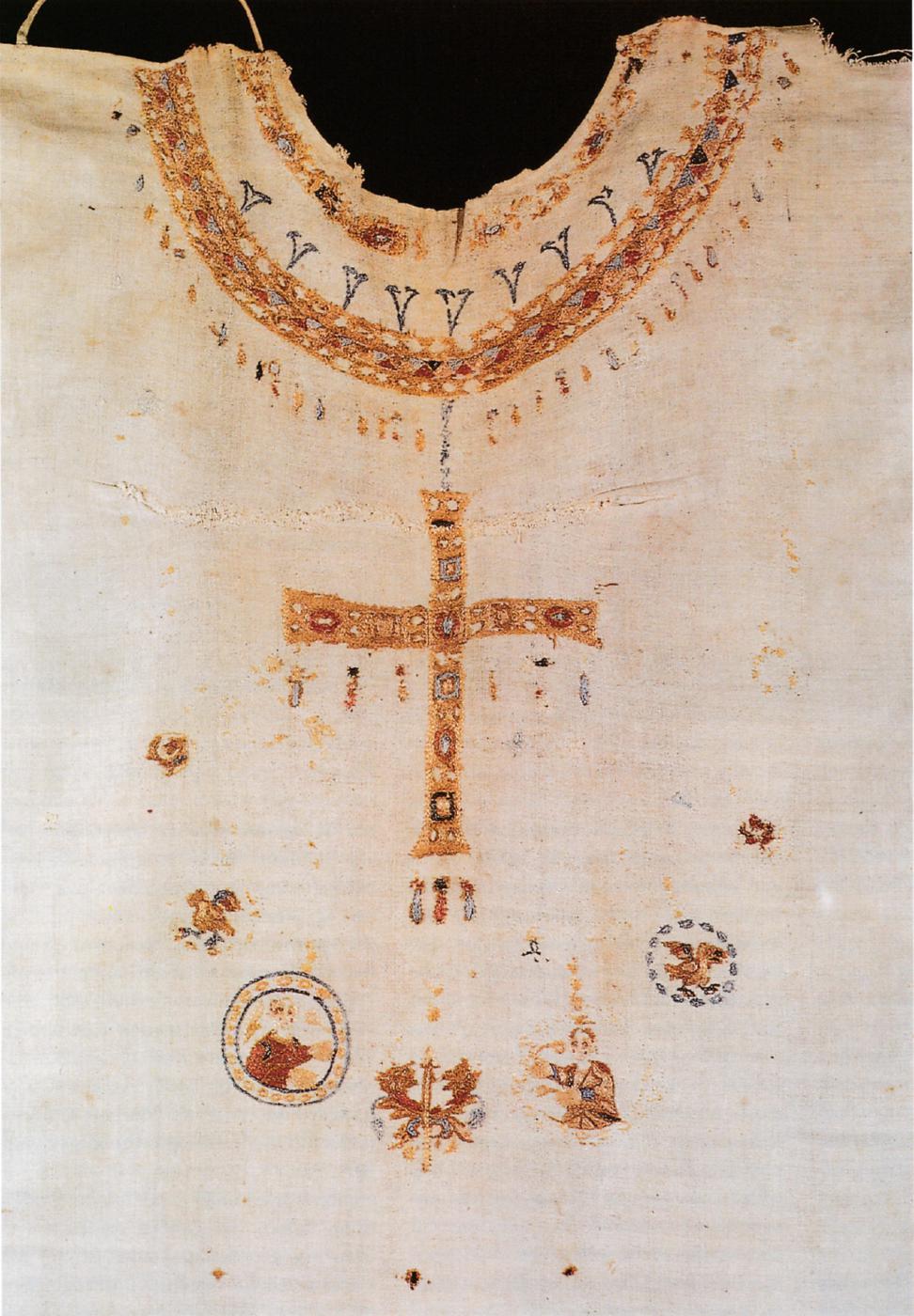

Approximately 100 years younger is the robe of Bathilde, wife of the Merovingian king Clodwig II. of Neustria and for some time regent for her underage son Chlothar III. She died in 680 and was buried in the Church of Saint-Croix in the monastery of Chelles, which she had founded.

Approximately 100 years younger is the robe of Bathilde, wife of the Merovingian king Clodwig II. of Neustria and for some time regent for her underage son Chlothar III. She died in 680 and was buried in the Church of Saint-Croix in the monastery of Chelles, which she had founded.

There is extensive embroidery on the chest of the robe. It depicts a "collar" from which hangs a pectoral cross, which in turn is surrounded by a chain of round medallions. Juwig describes the embroidery as follows: "Unterhalb des Halsausschnittes liegt ein goldfarbenes Band mit rechteckigen, runden und ovalen Binnenformen in roter, blauer und grüner Farbe. Darunter befindet sich ein breiter, ebenfalls goldfarbener Streifen aus drei Bändern mit runden und dreieckigen Binnenformen, welche alternierend mit roten und blauen Fäden gestickt sind. An dessen Ober- und Unterkante liegen blaue, blütenförmige Verzierungen und ein mehrfarbiges, tropfenförmiges Dekor. Im Scheitelpunkt des Bandes führt ein schmaler blauer Faden in Form kleiner Kettenglieder zu einem goldfarbenen Kreuz mit runden und eckigen Binnenformen sowie tropfenförmigen blauen und roten Applikationen. Um das Kreuz herumgeschwungen ist ein Faden mit neun Medaillons: Vier von ihnen zeigen vogelartige Wesen, deren Flügel, Krallen und Schnäbel bunt gestickt sind; zwei weitere zeigen menschliche Büsten mit unterschiedlich farbigen Gewändern. Im zentralen Medaillon umschlingen zwei farbige, greifenartige Wesen einen rankenverzierten Stab."[7] The embroidery is done freehand with silk thread using chain stitch and split stitch.[8]

Fig. 2: Drawings of the elements of the embroidery on Bathilde´s shirt.- In: Juwig, Carsten: Die Gewandreliquie der heiligen Bathilde. Überlegungen zur ihrem Bildstatus und Funktionskontext.- In: Juwig, Carsten/Kost, Catrin (Hrsg.), Bilder in der Archäologie – eine Archäologie der Bilder?, Münster 2010, S. 199

Fig. 3: Bathilde´s shirt. Silver embroidery on linen, Byzantine style.- In: https://www.heiligenlexikon.de/BiographienB/Bathilde.htm

No grave goods were placed with Bathilde, which makes the embroidery appear to be a "bildliche Substitution traditioneller Grabbeigaben"[9] at a time when the tradition of grave goods was generally being abandoned.[10] Juwig takes up the explanation that Bathilde deliberately commissioned the realistic depiction of her royal jewelry because she followed Eligius' request, as recorded in the vita of St. Eligius, to lay down her royal jewelry and give it to the poor[11], while Warmers agrees with the now generally accepted interpretation that that Bathilde had this embroidery made in order to "an ihren ehemaligen königlichen Rang zu erinnern" after her forced retirement from court[12].

Assuming that the embroidery depicts the actual royal jewelry of a Merovingian queen, analysis of the motifs clearly reveals the influence of the self-representation of the Eastern Roman and Lombard ruling houses, suggesting that the Merovingian court imitated the Eastern Roman Empire[13], which is not surprising, since "the Eastern Roman and then Byzantine empire remained the dominant cultural and political force in Europe and the Mediterranean—Byzantine art became a mark of high status, piety, and good taste."[14] With regard to the design, however, it is emphasized that "Ketten mit diversen runden Anhängern eine lange Tradition im merowingerzeitlichen Adelsschmuck des 6. und vor allem 7. Jahrhunderts haben"[15] and that "die Detailformen der gestickten Colliers […] ihre engsten Parallelen in Objekten [besitzen], die dem Umfeld des merowingischen Goldschmieds, Bischofs und Heiligen Eligius von Noyon zugeschrieben werden."[16] The embroidery on Bathilde's robe is thus a clear example of the fusion of different cultures from all over Europe, as had already been the case for the Germanic tribes during the Roman rule in Northern Europe.[17] This mutual influence was certainly promoted by the numerous migratory movements during the Migration Period, the subsequent Christianization of Western Europe, and the possibility of drawing on the global trade network of the Roman Empire, at least in large parts.

Despite the Europe-wide cultural exchange, one must ask where the skills in embroidery techniques came from and who produced the embroidery of the Merovingian period, given that just a few centuries earlier, embroidery was extremely rare and it was generally preferred to decorate textiles by weaving or printing.

The example of Bathilde's robe may provide an answer to this question. Bathilde was abducted from England as a child and ended up at the court of the Frankish mayors of the palace, where she lived as a slave before Clodwig II. married her. Since her marriage, Bathilde maintained close contact with the Anglo-Saxons of her homeland and, after living in the Chelles convent following her deposition, gathered numerous English women around her.[18] According to remains[19] and sources[20], embroidery was already widely practiced in England at that time.

Both Bede the Venerable (+672/673, +735) and the discovery of the maniple and stole of St. Cuthbert (*around 635, +687) make it clear that embroidery was practiced at a very high level in England in the 7th century. Embroidery was produced by women, especially nuns[21]. It was used to decorate churches, church vestments, and secular garments. Valuable silk fabrics were imported from Italy, Byzantium, and Asia to serve as the base for the embroidery[22]. The patterns were quite complicated and included both animal and human figures. Gold and silk embroidery in particular were famous throughout Europe and were in demand there for both ecclesiastical and secular use.[23] This, together with Bathilde's close relationship with England, suggests that the embroidery on the robe was made in England or by English women.

Assuming that the embroidery depicts the actual royal jewelry of a Merovingian queen, analysis of the motifs clearly reveals the influence of the self-representation of the Eastern Roman and Lombard ruling houses, suggesting that the Merovingian court imitated the Eastern Roman Empire[13], which is not surprising, since "the Eastern Roman and then Byzantine empire remained the dominant cultural and political force in Europe and the Mediterranean—Byzantine art became a mark of high status, piety, and good taste."[14] With regard to the design, however, it is emphasized that "Ketten mit diversen runden Anhängern eine lange Tradition im merowingerzeitlichen Adelsschmuck des 6. und vor allem 7. Jahrhunderts haben"[15] and that "die Detailformen der gestickten Colliers […] ihre engsten Parallelen in Objekten [besitzen], die dem Umfeld des merowingischen Goldschmieds, Bischofs und Heiligen Eligius von Noyon zugeschrieben werden."[16] The embroidery on Bathilde's robe is thus a clear example of the fusion of different cultures from all over Europe, as had already been the case for the Germanic tribes during the Roman rule in Northern Europe.[17] This mutual influence was certainly promoted by the numerous migratory movements during the Migration Period, the subsequent Christianization of Western Europe, and the possibility of drawing on the global trade network of the Roman Empire, at least in large parts.

Despite the Europe-wide cultural exchange, one must ask where the skills in embroidery techniques came from and who produced the embroidery of the Merovingian period, given that just a few centuries earlier, embroidery was extremely rare and it was generally preferred to decorate textiles by weaving or printing.

The example of Bathilde's robe may provide an answer to this question. Bathilde was abducted from England as a child and ended up at the court of the Frankish mayors of the palace, where she lived as a slave before Clodwig II. married her. Since her marriage, Bathilde maintained close contact with the Anglo-Saxons of her homeland and, after living in the Chelles convent following her deposition, gathered numerous English women around her.[18] According to remains[19] and sources[20], embroidery was already widely practiced in England at that time.

Both Bede the Venerable (+672/673, +735) and the discovery of the maniple and stole of St. Cuthbert (*around 635, +687) make it clear that embroidery was practiced at a very high level in England in the 7th century. Embroidery was produced by women, especially nuns[21]. It was used to decorate churches, church vestments, and secular garments. Valuable silk fabrics were imported from Italy, Byzantium, and Asia to serve as the base for the embroidery[22]. The patterns were quite complicated and included both animal and human figures. Gold and silk embroidery in particular were famous throughout Europe and were in demand there for both ecclesiastical and secular use.[23] This, together with Bathilde's close relationship with England, suggests that the embroidery on the robe was made in England or by English women.

Fig. 4: The so-called Masseik embroideries (detail) - -In: https://www.facebook.com/1131217773656788/

photos/a.1132094130235819/3160789460699599/?type=3 [abgerufen am 30.07.2025]

photos/a.1132094130235819/3160789460699599/?type=3 [abgerufen am 30.07.2025]

A proven example of English embroidery and the widespread distribution of these products are the eight surviving pieces of a chasuble, which date back to the 9th century.[24] They are named "Maaseik Embroideries" after the place where they are kept. The pattern bears similarities to other visual arts of the time, such as carvings, sculptures, and illuminations. The embroidery is done on linen fabric using gold thread and silk. Pearls and stones are also embroidered onto the fabric. The embroidery techniques used are stem stitch, split stitch, and appliqué[25] .

The fame of English textile manufacturing and processing is illustrated by Charlemagne's "order" of a coat made in England in 796[26] , which he wore himself. Regardless of this, Charlemagne expected his daughters to learn feminine skills, including embroidery.[27]

The fame of English textile manufacturing and processing is illustrated by Charlemagne's "order" of a coat made in England in 796[26] , which he wore himself. Regardless of this, Charlemagne expected his daughters to learn feminine skills, including embroidery.[27]

It is reported that Charlemagne preferred to dress according to old Frankish customs[28] . He rejected fashionable innovations such as short coats because they were impractical[29] . On festive days and at meetings with other rulers, however, he wore magnificent clothing[30] , probably to emphasize political goals and to clearly highlight his own position[31] . It can be assumed that Charlemagne, like other rulers before and after him, drew on the splendor of Merovingian royal clothing, which emphasized the continuity and legitimacy of royal rule and at the same time represented a promise for the future.

It can therefore be assumed that the clothing of the Carolingian rulers and nobility was also decorated with embroidery. This assumption is further supported by Charlemagne's efforts to be seen as the equal of the Byzantine Empire as the successor to the Roman Empire and to emphasize the "Nebeneinander von ost- und weströmischem Reich"[32] . Influences from Byzantium, where empresses and emperors traditionally appeared in richly embroidered garments, may therefore also have contributed to the lavish decoration of festive clothing in the Carolingian Empire with embroidery.

It can therefore be assumed that the clothing of the Carolingian rulers and nobility was also decorated with embroidery. This assumption is further supported by Charlemagne's efforts to be seen as the equal of the Byzantine Empire as the successor to the Roman Empire and to emphasize the "Nebeneinander von ost- und weströmischem Reich"[32] . Influences from Byzantium, where empresses and emperors traditionally appeared in richly embroidered garments, may therefore also have contributed to the lavish decoration of festive clothing in the Carolingian Empire with embroidery.

Fig. 5: Clothing of a king's daughter on her way to her wedding; Stuttgart Psalter, created around 830.- In: digital.wlb-stuttgart.de