Embroidery in ancient China and the Mediterranean region

Embroidery is an ancient textile craft used to embellish fabrics or decorate objects, and in principle it has changed little since its inception. Since the decoration of clothing and – by stretching – objects serves to satisfy the human need for beauty, it can be assumed that embroidery originated and was cultivated in cultures in which other basic needs were sufficiently met, i.e., that embroidery was developed in advanced civilizations. Accordingly, Falke calls it an "Kunst des Luxus"[1] and – comparing it to painting – "Nadelmalerei"[2].

The original embroidery techniques include

Embroidery is an ancient textile craft used to embellish fabrics or decorate objects, and in principle it has changed little since its inception. Since the decoration of clothing and – by stretching – objects serves to satisfy the human need for beauty, it can be assumed that embroidery originated and was cultivated in cultures in which other basic needs were sufficiently met, i.e., that embroidery was developed in advanced civilizations. Accordingly, Falke calls it an "Kunst des Luxus"[1] and – comparing it to painting – "Nadelmalerei"[2].

The original embroidery techniques include

- the running stitch, on which all other embroidery techniques are based[3] and which is most similar to sewing, i.e., joining two or more layers of fabric.

- the chain stitch, which was already in use in China around 1100 BC. It was executed with silk threads. Knowledge of this embroidery technique reached Europe via the Silk Road.[4]

- the buttonhole stitch, whose purpose is to prevent the fabric from fraying.[5]

- the satin stitch, which is used to fill areas on the embroidery fabric.[6]

- the cross stitch, which is worked over an even number of threads of the embroidery fabric in the shape of an x. The combination of cross stitches on an evenly woven embroidery fabric creates a pattern or image. It was the most popular embroidery stitch, especially since the Middle Ages.[7]

Embroidery in ancient China

As far as embroidery itself is concerned, the literature agrees that this art was already developed in China during the Bronze Age and was widespread there in the form of silk embroidery on a silk background[8]. This was probably facilitated by the invention of bronze working, which led to a more differentiated social structure with the emergence of a wealthy to rich upper class. Schuyler Cammann reports that the oldest evidence of the existence of embroidery dates back to China during the Shang Dynasty (18th-11th century BC), in the form of a bronze vase that had been wrapped in silk and used as a burial offering.[9] During excavations in Anyang, impressions of silk embroidery in chain stitch were found on its surface, together with a finely woven piece of fabric.

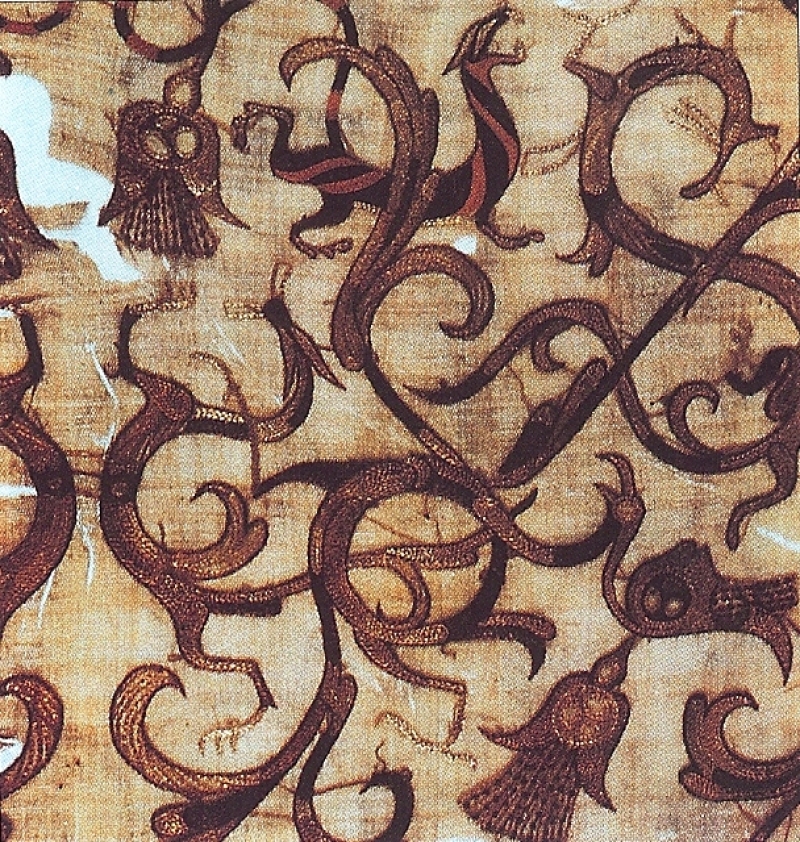

The oldest material evidence of embroidery currently known dates back to the 5th century BC, the period known as the Warring States period (475-221 BC): on the one hand, there is a silk fragment embroidered with a phoenix and a dragon using chain stitch[10]. The other is a silk fragment embroidered with a phoenix and a dragon using chain stitch and satin stitch[11]. In the tomb of a Chu official, various completely embroidered garments and objects with borders embroidered in chain stitch and satin stitch were discovered[12]. The finds also include a small piece of fabric bearing the weaver's signature and a red seal[13], possibly an indication of how the rigorous quality standards that already existed at that time, defined by the state[14], were controlled.

Fig. 1: Fragment of embroidery from Tomb No. 1 in Mashan, Jiangling, Hubei Province. Warring States period, 475-221 BC, chain stitch.-

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:%E2%80%9CChang_Shou

(longevity)_Embroidery%E2%80%9D_on_Thin_Silk_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:%E2%80%9CChang_Shou

(longevity)_Embroidery%E2%80%9D_on_Thin_Silk_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg

Fig 2: Fragment of embroidery from the Han Dynasty (206 BC-220 AD), symbols of immortality, chain stitch. - Probably part of a woman's dress.-

https://www.jessicagrimm.com/blog/chinese-embroidery

The fact that embroidery developed into a highly sophisticated craft in China is demonstrated by this fragment from the Han Dynasty (206 BC–220 AD): a cloud pattern in pink, orange, blue, and green symbolizes the Chinese belief in immortality[15]. This embroidery, like the geometric pattern found at the same time, was executed in chain stitch. Cammann points out, however, that during the Han Dynasty, satin stitch was also developed and used, in some cases even in appliqué technique, to avoid wasting silk thread on the reverse side[16]. Satin stitch became a dominant embroidery technique in Chinese embroidery[17].

Frick reports that during the Zhou dynasty (1045-221 BC), Chinese emperors had the insignia of the Son of Heaven, i.e., imperial dignity, painted and embroidered on their ceremonial robes[18]. Embroidery was evidently such a common art that the Chinese had their own character for it[19].

By the Han dynasty at the latest, artists and embroiderers were employed at court to create the imperial robes[20]. It is possible that professional designers and embroiderers were already employed at the imperial court during the Qin Dynasty (221-206 BC), as embroidered clothing already existed at that time[21], which presumably only the imperial family and very high-ranking officials could afford.

I was unable to find any evidence to support the assumption that cross-stitch originated in China in pre-Christian centuries[22].

By the Han dynasty at the latest, artists and embroiderers were employed at court to create the imperial robes[20]. It is possible that professional designers and embroiderers were already employed at the imperial court during the Qin Dynasty (221-206 BC), as embroidered clothing already existed at that time[21], which presumably only the imperial family and very high-ranking officials could afford.

I was unable to find any evidence to support the assumption that cross-stitch originated in China in pre-Christian centuries[22].

Embroidery in the Near East and the Mediterranean region in ancient times

In the Near East, the Phrygians, who had established a large empire in what is now Turkey since at least the 8th century BC and whose most famous king was Midas[23], were known for their embroidery. From the end of the 8th century BC[24], their "Prunkgewänder neben den Gürteln und Fibeln [zählten] zu den wichtigsten Handelsgütern"[25] to Ionia and Greece. In addition to the satin stitch, Speck also mentions the cross stitch as a common embroidery stitch[26], although no material evidence of this has been found. Since China had no contact with the West at that time and the important Silk Road trade route was not developed until later[27], it can be assumed that embroidery developed independently as a craft in Phrygia.

Although the Greeks appear to have adopted the art of embroidery from the Phrygians[28], the invention of embroidery is attributed to the goddess Pallas Athena in Greek mythology[29]. Ovid, however, has Arachne, whose skill in various handicrafts he praises[30] and who "mit der Nadel Bilder stickte"[31], deny that she learned from the master Pallas. Arachne considers herself at least equal to Pallas Athena.[32] Homer (presumably 2nd half of the 8th century BC – 1st half of the 7th century BC[33]) tells in the 14th book of the Iliad of the embroidered colorful belt that Hera asks Aphrodite for as an aid to seduce her husband Zeus[34]. In his time, the women of Sidon were said to have been particularly skilled embroiderers[35].

Knowledge of Greek embroidery has been preserved primarily through figurative representations and vase paintings. For example, there were embroidered, close-fitting necklaces[36] and "Gruppen von menschlichen Figuren und Thieren geschmackvoll gestickt als breiter Besatz von Frauengewändern"[37]. In general, the Greeks seem to have used embroidery primarily to decorate the hem and sleeve hem of the chiton with braids[38]. Due to the lack of textile remains, it is not possible to determine which embroidery techniques were used.

Unlike the Greeks, the Romans did not draw on mythology to derive the origin of embroidery from the gods. Instead, they recognized the special quality of Phrygian embroidery to such an extent that Pliny the Elder described the "Kunst Malereien in Kleider zu sticken" as an invention of the Phrygians[39]. Accordingly, embroiderers were referred to as phrygiones[40]. This recognition of the cultural achievements of the Phrygians can possibly be explained by the Roman tradition of incorporating both deities and the cultural and economic achievements of subjugated peoples into Roman culture[41] and integrating them – a tradition that certainly left the subjugated peoples with a sense of value. Of course, it could also simply be that, due to the diverse trade relations, news and knowledge had become so commonplace that it would have been ridiculous to claim a different origin for the embroidery than its actual one.

The equation of embroidery with the "Kunst Malereien in Kleider zu sticken" seems to limit the application of embroidery to the decoration of clothing, which is supported by the remains of painted ceramics. An early depiction from Apulia, dated to the 4th century BC, already shows embroidery serving as decorative elements on clothing[42].

The equation of embroidery with the "Kunst Malereien in Kleider zu sticken" seems to limit the application of embroidery to the decoration of clothing, which is supported by the remains of painted ceramics. An early depiction from Apulia, dated to the 4th century BC, already shows embroidery serving as decorative elements on clothing[42].

Fig 3: Oinochoe, Apulia, 4th century BC, woman's head with pearl jewelry, halo, embroidered headscarf, and tania around the hair bun. - Stadt Duisburg, Kultur- und Stadthistorisches Museum Duisburg, Sammlung Köhler-Osbahr, Band I: Auswahlkatalog Münzen und Antiken, Duisburg 1990, S. 44 (Abb. 70)

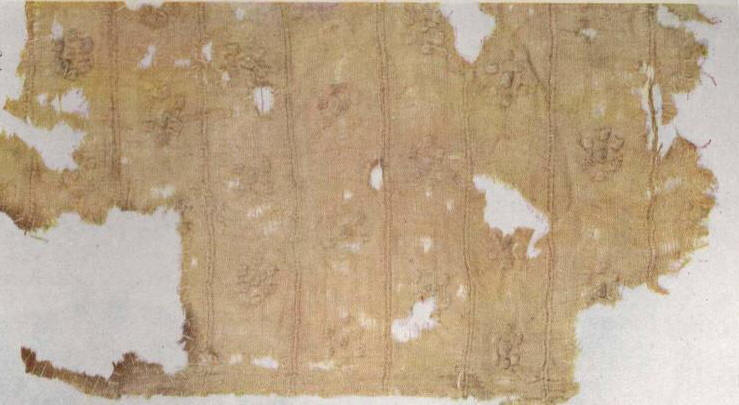

The "standard garments" of the Romans, the tunic and the white toga, were particularly suitable for decoration with embroidery. The tunic often had two stripes that ran "auf der Vorder- und Rückseite senkrecht vom Halsausschnitt bis zum unteren Saum"[43] and were either woven, sewn on, or embroidered[44]. In the Republican era, they were called angusticlavia because of their narrowness; they served to indicate the rank of the wearer[45]. In the Imperial era, this function was lost, but the variety of colors, ornamentation, and quality of the embroidery demonstrated the wearer's wealth and were thus an indirect status symbol[46].

The Roman toga, which was normally white, could also be decorated with stripes of varying widths to indicate rank. Already during the time of the Republic[47], consuls and triumphators[48] were allowed to wear "eine purpurne, mit reichen Goldornamenten bestickte Toga"[49] (the toga picta), which the Romans attributed "entweder auf die Tracht ihrer Könige oder auf das Gewand ihres obersten Gottes Jupiter"[50], but which was in fact of Etruscan origin[51]. The triumphator was also allowed to wear a palm-embroidered undergarment, the tunica palmata[52]. These special garments became imperial regalia during the reign of Augustus; during the imperial period, the chlamys, known since Alexander the Great, was also worn in some cases, which was also embroidered.[53]

The Roman toga, which was normally white, could also be decorated with stripes of varying widths to indicate rank. Already during the time of the Republic[47], consuls and triumphators[48] were allowed to wear "eine purpurne, mit reichen Goldornamenten bestickte Toga"[49] (the toga picta), which the Romans attributed "entweder auf die Tracht ihrer Könige oder auf das Gewand ihres obersten Gottes Jupiter"[50], but which was in fact of Etruscan origin[51]. The triumphator was also allowed to wear a palm-embroidered undergarment, the tunica palmata[52]. These special garments became imperial regalia during the reign of Augustus; during the imperial period, the chlamys, known since Alexander the Great, was also worn in some cases, which was also embroidered.[53]

Fig. 4: The Etruscan nobleman Vel Saties in the toga picta, fresco from the Francois tomb near ancient Vulci, 4th century BC.- https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tomba_Fran%C3%A7ois#

/media/Datei:Fran%C3%A7ois_Tomb_Painting_03.jpg

While embroidery on men's clothing thus followed a certain tradition, embroidered garments for women were quite controversial in Roman society. "In der Zeit des Augustus unterschied man zwischen den tugendhaften Web-Matronen einerseits, die sich in Stola und Palla aus Wolle kleideten, und den höheren Töchtern andererseits, die goldbestickte Kleider trugen (inaurata veste), ihre Haare parfümierten, häufig ihre Frisur änderten und ihre Hände mit Gemmen schmückten, um fremde Bewunderung auf sich zu ziehen."[54] Conservative Romans condemned this form of ostentatious display of luxury as a serious violation of good morals, the mos maiorum[55] .

Unfortunately, the preserved remains and sources do not provide any insight into the embroidery techniques used. Pliny's phrase "Malereien in Kleider zu sticken" suggests that floral, animal, and figurative motifs were used, which, due to their curves, were usually executed in satin stitch and chain stitch. Embroidered clavi, on the other hand, may have had a braid-like character, for which geometric patterns that can be executed in cross-stitch could also be used. However, due to the small number of material remains, we can only speculate.

The situation is different when it comes to sources relating to the advanced civilizations of the Arab world.

During the excavations and openings of the royal tombs, not only were linen textiles found whose quality, at 100 threads/cm, far exceeds today's quality of approx. 35-40 threads/cm[56] , but textiles featuring genuine embroidery were also found in the tombs of Thutmose IV(1397-1388 BC) and Tutankhamun (1332-1323 BC). They prove that embroidery had been practiced in Egypt for a long time and had achieved a high level of quality.

Unfortunately, the preserved remains and sources do not provide any insight into the embroidery techniques used. Pliny's phrase "Malereien in Kleider zu sticken" suggests that floral, animal, and figurative motifs were used, which, due to their curves, were usually executed in satin stitch and chain stitch. Embroidered clavi, on the other hand, may have had a braid-like character, for which geometric patterns that can be executed in cross-stitch could also be used. However, due to the small number of material remains, we can only speculate.

The situation is different when it comes to sources relating to the advanced civilizations of the Arab world.

During the excavations and openings of the royal tombs, not only were linen textiles found whose quality, at 100 threads/cm, far exceeds today's quality of approx. 35-40 threads/cm[56] , but textiles featuring genuine embroidery were also found in the tombs of Thutmose IV(1397-1388 BC) and Tutankhamun (1332-1323 BC). They prove that embroidery had been practiced in Egypt for a long time and had achieved a high level of quality.

Fig. 5 Fabric embroidered with rosettes from the tomb of Thutmose IV.

Fig. 6: Details of embroidered borders from the tomb of Tutankhamun

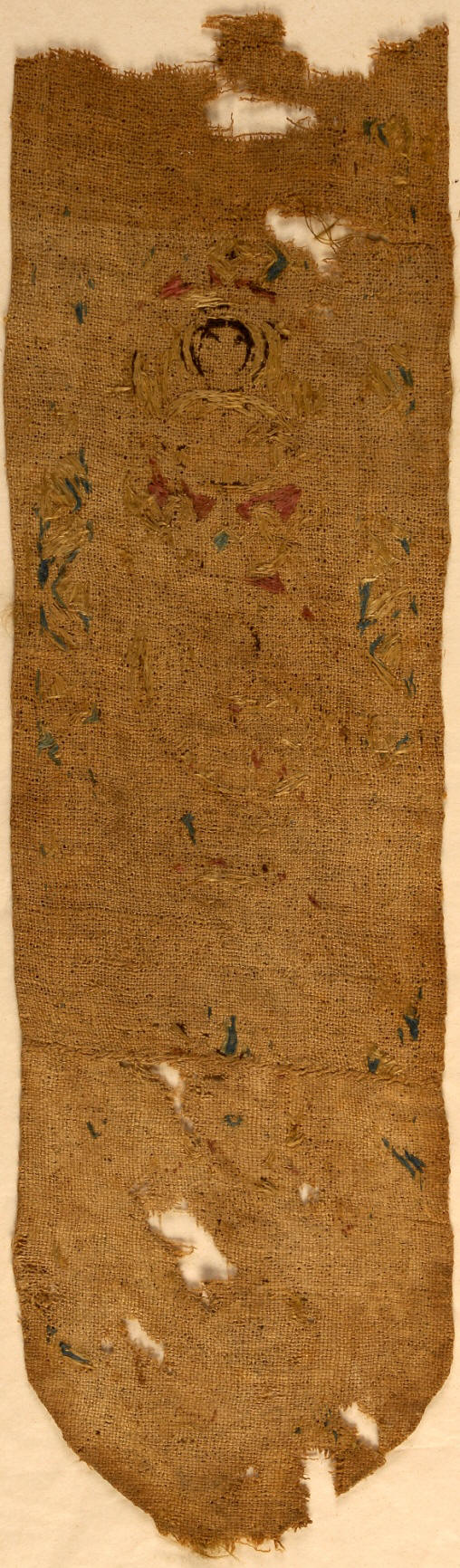

In general, the dry, hot climate of the desert region ensured that textiles could be preserved. In Egypt in particular, excavations of tombs have uncovered textiles that are generally referred to as "Coptic" textiles. This term initially suggests that these are fabrics that originated from the Christian inhabitants of Egypt, especially since embroidery is mentioned in the Bible[57]. However, there is broad consensus in the literature that "das Adjektiv „koptisch” in Zusammenhang mit Kunst und Kultur nicht primär christlich, sondern eher „ägyptisch“ hinsichtlich der geographischen Herkunft und einer bestimmten Zeitspanne bedeutet"[58]. The time period is given as the 3rd to 10th centuries AD[59]. Due to the lack of care in documenting and handling the finds excavated since the 19th century, their dating is often only possible by comparing the symbolism, colors, and manufacturing techniques[60] . "Über die von den Kopten verwendeten Textilien geben Wandmalereien und Mosaiken sowie Grabfunde Aufschluss. Wurde ein Grab sachgemäß gehoben, so konnten oft vollständige Gewänder oder Behänge geborgen werden. Erhalten sind auch Wandbehänge, Teppiche, Vorhänge und Möbelstoffe, wie Matratzenbezüge, Kissenhüllen und dickere Decke"[61].

Some of the embroidery on Coptic textiles incorporates very old patterns from Asia[62]. The most common embroidery techniques are satin stitch, running stitch, and chain stitch[63]. Occasionally, the overcast stitch is also used.

Some of the embroidery on Coptic textiles incorporates very old patterns from Asia[62]. The most common embroidery techniques are satin stitch, running stitch, and chain stitch[63]. Occasionally, the overcast stitch is also used.

Fig. 7: Clavus of a tunic with fragments of embroidery in running stitch and chain stitch, 6th/7th century. - Laura Klama, Bestandskatalog der koptischen Textilien im bayerischen Nationalmuseum, München 2009, Kat.-Nr. 56

Fig 8: Fragment of a strip (of a clavus?),

embroidery made with chain stitch and overcast stitch, undated.- Landesmuseum Stuttgart, Die koptischen Textilien im Landesmuseum Württemberg, Stuttgart 2016, Nr. 104

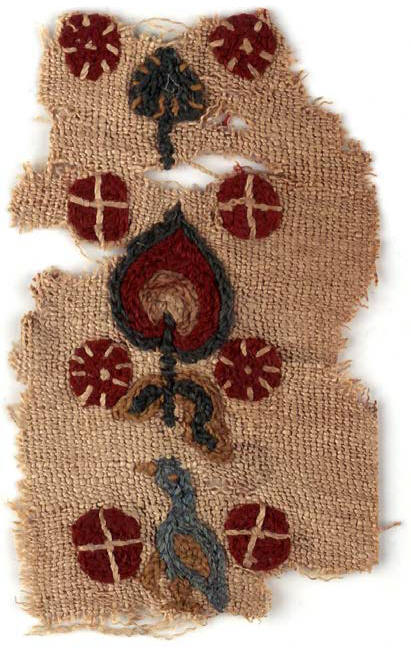

"Das sonst so beliebte einfache Verfahren des Kreuzstichs wurde damals im Nillande anscheinend nur ausnahmsweise gepflegt,"[64] according to Ernst Kühnel, who reports on Islamic fabrics in Egyptian tomb finds and refers to a find dating from the 14th/15th century[65]. Unfortunately, he does not go into detail about when and in which regions cross-stitch was "so beliebt" as an embroidery technique. The Bavarian National Museum has a fabric fragment from the 7th/8th century that may have been part of a hanging. The natural-colored linen fabric features woven and embroidered ornaments, with the embroidery including red and blue cross-stitches[66].

Overall, it can be concluded from the literature and the material remains that cross-stitch was not frequently used as an embroidery technique in the ancient Mediterranean region, even though it was known. Forrer explains that the "hochentwickelte und vielgeübte Wirkerei" did not allow embroidery to flourish, although "hie und da […] kleine Kreuze […] eingestickt [waren]"[67]. Another reason could be that curves in particular are not as easy to execute in cross-stitch as with other techniques, so that priority was given to the latter.

In any case, the widely held view that cross-stitch is the oldest embroidery technique cannot be upheld by the findings.

Overall, it can be concluded from the literature and the material remains that cross-stitch was not frequently used as an embroidery technique in the ancient Mediterranean region, even though it was known. Forrer explains that the "hochentwickelte und vielgeübte Wirkerei" did not allow embroidery to flourish, although "hie und da […] kleine Kreuze […] eingestickt [waren]"[67]. Another reason could be that curves in particular are not as easy to execute in cross-stitch as with other techniques, so that priority was given to the latter.

In any case, the widely held view that cross-stitch is the oldest embroidery technique cannot be upheld by the findings.

Fig. 9: Fragment of embroidery on natural-colored linen fabric, embroidery consisting of cross-stitches and embroidered V-motifs and lettering, 7th/8th century.- In: Laura Klama, Bestandskatalog der koptischen Textilien im bayerischen Nationalmuseum, München 2009, Kat.-Nr. 57